While the absence of any negative surprise in the Budget got a thumbs-up, tepid global growth and weakness in world trade might keep stock markets range-bound in 2016

While the absence of any negative surprise in the Budget got a thumbs-up, tepid global growth and weakness in world trade might keep stock markets range-bound in 2016

They say a week is a long time in politics.

It seems to be even longer in the financial markets.

A week ago, the mood on Dalal Street was sombre and India the worst performing stock market in the globe, except China, on a year-to-date basis.

Five days hence, the benchmark BSE Sensex is among the top performing major global stock indices.

The market gained nearly seven per cent in the four trading sessions of March, bringing cheer back in trading rooms as investors’ portfolios are looking much better.

Is the worst behind for the economy and corporate India? Have the Budget proposals for 2016-17 resolved the various tensions that plague India’s growth story? The answer is both yes and no.

“Economic conditions on the ground remain the same but the Economic Survey and the Union Budget reassured the market that things cannot get worse.

"In other words, economic growth, corporate earnings and interest rate cycle has most likely bottomed out and will improve from here.

"Financial markets treated it as a positive signal,” says Madan Sabnavis chief economist, Care Ratings.

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley’s promise to stick to a fiscal deficit target of 3.5 per cent of gross domestic product in 2016-17 removed the fiscal sword hanging on financial markets for now.

Yields on the 10-year government bond had hardened in the run-up to the Budget, despite a cut in benchmark interest rate by Reserve Bank of India.

Costlier credit is always bad for corporates and equity investors (See chart).

In all, benchmark interest rates had jumped nearly 37 basis points from the lows of October 2015, driven by higher borrowings of various state governments.

The fear was that if the Centre were to raise borrowing, it would push up interest rates even higher, hurting recovery in corporate capex cycle and make equity investments unattractive compared to fixed income instruments.

The finance minister belied the fear and said he would keep market borrowings almost at last year’s level.

In all, the Centre plans to borrow Rs 6 lakh crore in FY17, up 2.7 per cent from the current year.

The impact was immediate. Bond yields declined by nearly 20 bps on Budget Day itself and remain under pressure.

This charged up the bulls on Dalal Street.

There has also been a positive bias towards equities globally in the first week of March and markets across the world have rallied.

For India, the long-term growth challenge remains unchanged.

The government’s spending on the rural sector, and higher public sector salaries on account of the Seventh Pay Commission awards and One Rank One Pension could provide a short-term demand boost for consumer companies but it may not resolve the problem of lower and declining capacity utilisation in the industrial and infrastructure sector.

And, if the Budget projections about revenue growth in FY17 fall short of the target forcing the government to borrow more, then it may again put upward pressure on bond yields and interest rates.

“Tax revenues are expected to grow at twice the rate achieved in the current fiscal.

"Besides, the government expects large gains from telecom spectrum auction and divestment of public sector companies.

"Any slippage here could create a fiscal hole of around Rs 1.25-1.5 lakh crore (Rs 1.25-1.5 trillion) on revenue side pushing-up fiscal deficit for FY17,” says Dhananjay Sinha, head -- institutional equity, Emkay Global Financial Services.

The India growth story remains under challenge from a tepid recovery in global growth and world trade.

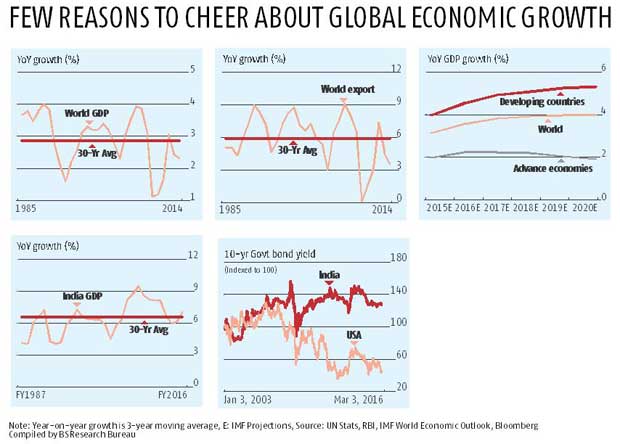

The recovery in the world economy after the Lehman crisis has been weaker than any time in the past 30 years (see chart).

The recovery in the world economy after the Lehman crisis has been weaker than any time in the past 30 years (see chart).

International Monetary Fund expects acceleration in global growth over the next five years but it’s largely contingent on a faster growth in the US and in developing and emerging markets.

The latter is contingent on US’ appetite for foreign products and services besides a robust global commodity market.

Even as some experts believe commodity prices may have bottomed out, how the commodity cycle plays out remains to be seen.

This makes it tough for India to crank up its growth engine given that goods and services exports accounted for nearly a quarter of the country’s gross domestic product in FY15.

The new GDP series projects a shallower recession than in the previous downturn but corporate earnings are still to show the strength visible in early 2000s (see charts).

All this calls for a cautious optimism and the best hopes for equity investors in the current year would be a trading market that fails to breach a new low.