Failure to increase domestic production and rising local demand has made Modi’s targets impossible to achieve.

Twesh Mishra reports.

India’s dependence on imported crude oil to meet domestic demand has been a matter of concern for years.

Delivering the inaugural address at the global energy summit — Urja Sangam — in 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had called for enhancing domestic oil and gas production to cut the import burden.

He aimed at lowering it by at least 10 per cent by 2022 — to coincide with the platinum jubilee of India’s independence.

But this target is far from being achieved and the country’s import reliance has only risen.

“India is dependent on imports to meet 77 per cent of our energy requirements from the oil, gas and petroleum sector.

"Can it be that by August 15, 2022, we will be able to bring this import dependence down by at least 10 per cent?

"This lowering of import will be by hiking domestic production by 10 per cent.

"Once we are able to do so, by 2030, we can cut imports further by 50 per cent,” Modi had said.

Instead of cutting imports by 10 per cent, its proportion has continued to rise from 2015.

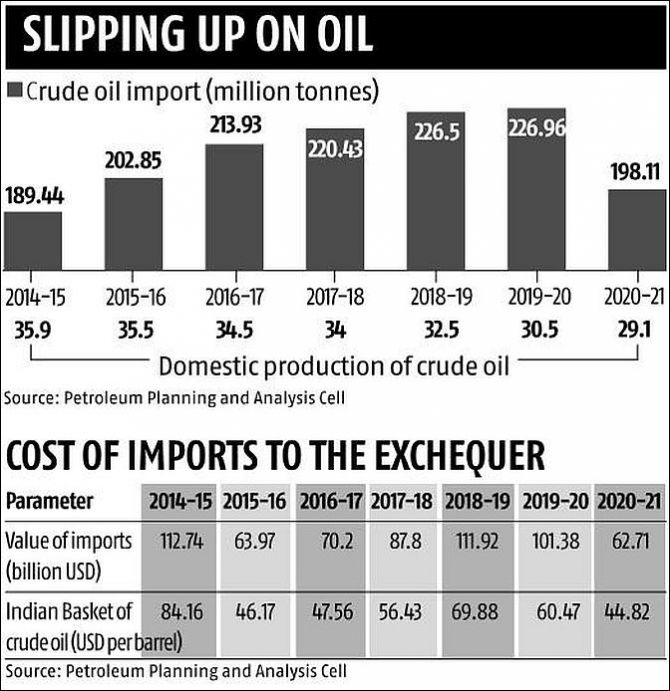

Annual domestic crude oil output has fallen to below 30 million tonnes (mt) and total import has risen to 226 mt.

The failure to increase domestic production and rising local demand has made Modi’s targets impossible to achieve.

Offering some relief, domestic demand for fuel had tempered a bit during the Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020 and for a part of 2021 (see “Slipping up on oil”).

But fuel demand is expected to return to pre-Covid levels by the end of 2021.

Domestic production of crude oil, however, might not keep pace.

When Modi had given his import reduction call in 2015, domestic crude oil production stood at 35.5 mt (2015-16) but has fallen to 29.1 mt in 2020-21.

The slowdown in crude oil production was partly on account of the lockdown; ageing fields that form the mainstay of domestic output are also drying up fast.

These fields were awarded by the earlier governments under various fiscal regimes.

The ministry of petroleum and natural gas has made attempts to offer more acreages for oil and gas exploration, and production, but these exercises have not helped much.

The slow pace of approvals coupled with crude oil price volatility has made monetising existing and fresh discoveries difficult.

These new batches of oil and gas assets were given out under a liberalised fiscal regime with a focus on maximising production.

But participants in the Open Acreage Licensing Policy (OALP) and the Discovered Small Field (DSF) bid rounds, both conducted by the Modi government, are struggling to start production.

Making things worse for India, the price of Brent, the most popular marker for crude oil, is now around $75 a barrel from an average $64 a barrel in 2019.

This puts significant pressure on India that has to rely more on imports for meeting its needs.

The Indian Basket of crude oil, the price at which Indian refineries buy crude oil, stood at $73.59 a barrel on June 29.

“Dependence on imports of crude oil was 86 per cent for domestic consumption in 2020-2021.

"Import dependence is likely to remain at 86-87 per cent for financial year 2021-2022 as well,” said Prashant Vasisht, vice-president and co-head, corporate ratings, ICRA.

This reliance on imports puts Indian fuel prices at the mercy of global cues.

Coupled with the state and central taxes, petrol and diesel prices in the country have risen to record levels, hurting consumers across sectors.

High diesel prices, which have crossed Rs 100 a litre in some states, are jacking up inflation due to more expensive transport costs.

Higher crude oil prices will continue to directly impact fuel prices, which are at their peak, in the absence of any steps taken to reduce taxes, said Bhanu Patni, senior analyst at India Ratings and Research.

In Delhi, the price of diesel has risen from Rs 73.87 a litre on January 1 to Rs 89.18 a litre on June 30.

Devendra Pant, chief economist and head public finance, India Ratings, notes that the higher diesel prices have a severe cascading effect.

“A 10 per cent increase in diesel prices will result in a 31 basis point increase in wholesale inflation directly,” making all commodities dearer.

During his 2015 address, PM Modi had also said, “If we need to achieve global benchmarks, then we need to be self-sufficient in the energy sector.

"There can be new sources of energy that can emerge, even those that we are not aware of right now.”

This seems to be the direction in which India is moving.

“It’s quite clear now that India’s crude oil and liquefied natural gas import dependency cannot be brought down by ramping up domestic exploration and production.

"It can only happen through a massive push for biofuels and electrification of energy consumption, and sourcing that electricity from renewable energy, particularly solar,” said Debasish Mishra, leader (energy, resources and industrials), Deloitte in India.

“With storage technologies, hydrogen fuel cells, among others, becoming commercially viable in the next couple of years, India may realistically be able to reduce its fossil fuel import dependency,” Mishra added.

India is also betting on ethanol to trim import requirements.

In this direction, targets for blending ethanol with petrol have been advanced.

There is also a sliver of hope from natural gas, where India meets just half its domestic demand from imports.

Experts say that domestic gas production would rise by around 25 per cent in 2022, allowing leg room to trim imports there.

But these moves will impact crude oil imports by a small fraction and Modi will face much disappointment about his 2022 goal.

Photograph: Reuters