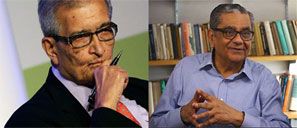

Only reforms that accelerate economic growth can generate the revenues to finance expenditure on social infrastructure for the poor, not the other way round, insists Jagdish Bhagwati.

My “debate” with Mr Sen has now descended into the political morass after Mr Sen gratuitously attacked Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi as unfit to be India’s prime minister. I find such pronouncements to be jejune and deplorable. In fact, my position has always been that I write for the public like Keynes did; and my ideas are available to every progressive politician, no matter what his party.

Also, I have insisted that I vote after studying the platform of a candidate for office; and would want public debates, US-style, between the front runners (possibly Rahul Gandhi and Narendra Modi), without which no informed decision can be taken by voters.  Having dragged himself into the political maelstrom, Mr Sen now faces predictably gutter politics, as (I am told) lascivious photos of his actress daughter are circulating on the internet.

Having dragged himself into the political maelstrom, Mr Sen now faces predictably gutter politics, as (I am told) lascivious photos of his actress daughter are circulating on the internet.

His appointment of himself as the Chancellor of the new Nalanda University and of an unknown academic as the vice chancellor at an astonishingly high salary has led to accusations of corruption. In fact, the former President of India Abdul Kalam had written a letter saying, among other distressed complaints, that these functionaries would have to reside in Nalanda, that letter was suppressed and has now been released under the Right to Information Act.

It now seems also as if Mr Sen asked for and accepted a million dollars from Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha for his new non-governmental organisation, whereas I have not asked for a rupee or received any financing from the BJP I am supposed, by Mr Sen’s media friends, to be supporting. As Alexander Pope wrote, everything seems yellow to the jaundiced eye.

All this is a massive distraction, attributable to Mr Sen, from any reasonable debate between us. The ideal way to confront differences is to debate them face to face. I have indeed had several such debates, over the years, with Ralph Nader (twice, once in Seattle in 1999 in the Town Hall with almost a thousand people rooting for him), Lorie Wallach, Naomi Klein, the environmentalist Goldsmith, leading American protectionists, on BBC with a French mayor complaining about Hoover leaving for England, and many others.

For reasons he can best speak to, Mr Sen prefers the comfort of singing madrigals together with his friends who are respectful of him; and he has publicly stated that while I want to debate him, he does not want to debate me.

But then, what are the differences between us? Many argue that there are none. Montek Ahluwalia and Kaushik Basu have said so: but both are bureaucrats and no one expects them to offer sincere opinions.

Some also fall victim to the cultural tradition of obfuscation implied by Asti Nasti. Others feel uncomfortable challenging celebrities and are into the Sashtanga Pranam mode which requires pretending that both sides are saying the same thing and are therefore both are right.

Surprisingly, Finance Minister Mr Chidambaram, who is a brilliant man with a gift for writing (I once released his book of essays written while he was out of power and said that he wrote so well that one wished that he was out of power more often!), has fallen victim to this fallacy.

He is seduced by his clever phrasing, saying that Bhagwati has a passion for growth whereas Sen has compassion for the poor. But that is precisely where he goes wrong and where we must focus to put Mr Sen in his place, which is certainly not on a pedestal.

Since the 1960s when I worked on poverty eradication in the Planning Commission when Mr Sen was hardly active in this cause, I was for growth, not per se, but because I have compassion for the poor. Growth was a strategy; poverty eradication was the objective.

This has often been stressed by critics such as Professor T N Srinivasan; but the contrary myth that we worshipped growth for its own sake persists. Empiricism is not a hallmark of our culture. Mr Sen and his Pakistani friend Mahbub Haq were behind this self-serving myth.

There is no reason for this myth to be perpetuated. I personally gave a copy of the Bhagwati-Panagariya book to the finance minister who put it into his briefcase bulging with files. Evidently, he is a busy man and has had no chance to read the book. I urge that he do so forthwith before he pronounces erroneousl y again on the subject of what I stand for.

y again on the subject of what I stand for.

This is important, since the thesis that growth would pull the poor above the poverty line, however drawn, really divided Mr Sen from me. The experience after the growth-enhancing reforms (which we call Track I reforms) were massively initiated in 1991 only proved me right. Poverty declined significantly with the growth.

I had also emphasised that growth would produce increased revenues that then could be used to finance social expenditures on health and education for the poor — which every five-year plan had embraced as our objective. These were called by us Track II reforms.

While I was among the intellectual pioneers of the Track I reforms that transformed our economy and reduced poverty, and witness to that is provided by the prime minister’s many pronouncements and by noted economists such as Deena Khatkhate, I believe no one has accused Mr Sen of being the intellectual father of these reforms. So, the fact is that this huge event in the economic life of India passed him by.

Mr Sen would like us to believe that Track II expenditures would have reduced poverty and even produced growth. But beyond assertions, he has no convincing argument on his side. As I (and Professor Panagariya) argue, India had too few rich and too many poor.

Redistribution (i.e. taking moneys from the rich and distributing it to the poor) would have increased their well-being only marginally. Growth had to come first, then “redistribution” from the enhanced revenues unless God was to drop manna from heaven! Mr Sen lives in a world of illusion.

So while Track II expenditures can increase only if Track I reforms generate growth and hence revenues, Mr Sen is leading planners/politicians down a dangerous path by pretending that, even though growth rates have fallen in the last two years and Track I reforms have also slowed down, we can still increase dramatically social spending on the Food Security Bill, in particular.

That way lies inflation and hence damage to the poor who are victimised most by inflation. Mr Sen has seen many economists note this; but he refuses to answer the criticisms and simply hides behind his reputation as being “for the poor”!

Our differences with Mr Sen also extend regarding the optimal design of the Track II expenditures when revenues for them are available. The limited ability of the government to deliver food, education and health and the associated leakages along the elaborate bureaucratic delivery systems notwithstanding, Mr Sen denounces their provision by the private sector and insists that the government alone must provide them.

In contrast, under Track II reforms, I advocate putting the money in the hands of the beneficiaries and letting them decide whether they want to purchase food, education and health from private or public providers.

In conclusion, the bottom line is that Mr Sen hurt the poor by being lukewarm at best, and opposed at worst, to many of the growth-enhancing Track I reforms (as amply shown in our book): this was a sin of omission. Now by uncritically supporting Track II expenditures in the face of declining revenues, he is again hurting the poor: this is a sin of commission. The epitaph for the debate Mr Sen would not have is quite simply: The Debate that was Not.

The author is University Professor (Economics, Law and International Affairs) at Columbia University. This is an edited version of an article that appeared on his website