If you live in a large Indian city, be it Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, Kolkata, Hyderabad or Chennai, can you visualise a time in the future when your city would be free of traffic chaos, parking nightmares, power cuts and water shortage?

If that sounds like a distant dream, then that's exactly the image that the government is trying to conjure up for Delhi through the implementation of the recently unveiled Master Plan for Delhi-2021 (MPD-2021).

The Plan authored by Delhi Development Authority (DDA), the civic authority of the country's capital, and approved by the Ministry of Urban Development, encapsulates the city's problem areas, issues intrinsic to urban living, and advocates solutions to various problems.

Background: This is the third Plan after the Master Plans of 1962 and 2001. The draft MPD-2021 was thrown open to public for suggestions and objections in March 2005. Two years on the stock, multiple modifications and 8,000 objections later, the Central government finally notified the Plan on February 7 this year.

Ever since it was unveiled, the Plan evoked sharp reactions. The Plan's critics have labelled it a political document and a mere wish list. They point out that political expediencies have caused some of the current civic mess. For instance, growth of slums was allowed as they served as vote bank for political parties. They argue that if the political inclination remains unchanged, the ills will never get cured.

In this backdrop, Outlook Money decided to delve into the document to dig out the provisions in areas like housing, parking, utilities (water and power) and physical infrastructure. The idea was to give an impact assessment of the major proposals on the problems they seek to address.

Housing

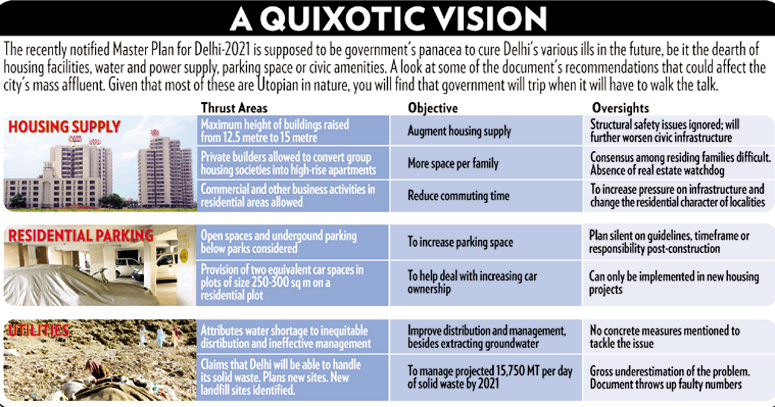

Vertical solutions: The MPD-2021 takes cognisance of the fact that there is shortage of housing stock and has based its conclusion on the projected population of 230 million in the city by 2021. The housing requirement is expected to be 24 lakh (2.4 million) dwelling units. The Union Minister of State for Urban Development Ajay Maken, a driving force behind the Plan, believes that by allowing buildings to expand vertically, this problem can be solved -- something that gets reflected in the Plan. The Plan suggests that the maximum height of the building in all plots be raised to 15 metres from 12.5 metres, including the ground floor and three other floors (See below: A Quixotic Vision).

Re-development scheme: The Plan also suggests a redevelopment scheme that lays down the provision of individual families in group housing societies pooling their resources and roping in a private builder to construct high-rise apartments. "The families subscribing to the scheme will get 1.5 times floor area ratio (FAR) than the existing one. We need to incentivise people so that they consider this option," says Maken. Currently, this scheme can be worked out only in a minimum of 3,000 square metre area.

"But we can consider reducing the area if people take up this redevelopment scheme," says Maken. The Plan, for the first time, talks about the involvement of the private sector for the development and redevelopment of housing. Understandably, the industry welcomes the move. "The step is well-timed as the real estate sector opened to foreign direct investment in 2005," says Vivek Dahiya, associate director, DTZ India, a real estate advisory and consultancy firm.

To combat housing shortage, 22,000 hectares of land, where currently the scope for individual housing doesn't exist, will be unlocked for fresh development.

While going vertical is supposed to enhance housing supply, there is a catch. "Structural safety issues haven't been given much thought," feels K.T. Ravindran, a reputed urban designer and Dean of Studies, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi. "Certain areas of Delhi are more susceptible to earthquake and should be spared from heavy densification. Besides, this will only worsen the civic infrastructure," he opines.

The problems of going vertical doesn't end there. To erect high-rise structures, the essential precondition of obtaining general consensus from residing families will always be an uphill task.

Besides, home-owners will continue to be vulnerable in the absence of a real estate regulatory body, monitoring the activities of builders.

Mixed land use

The Plan's notification of 2,183 streets for commercial and mixed-land use activities and the regularisation of (more than 1,500) unauthorised colonies on private and public land have drawn a lot of resentment from Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs). They say commercial activities in residential areas got regularised because shopkeepers allegedly funded candidates and parties during election campaigns.

Says Pankaj Aggarwal, secretary of the Delhi's RWA: "Those who have been in line with the law feel cheated. It sends a signal to the people that it is disadvantageous to be honest and tax compliant. The city is setting a bad example for other cities." The truth is that the move not only threatens the residential character of the colonies but raises security concerns as well. Besides, it threatens to increase the pressure on the civic infrastructure.

Says Ravindran: "Politicians should be made directly responsible for such decisions and the implementation of the Plan should be made co-terminus with the politician's tenure."

Power and water

How does the MPD-2021 sort out Delhi's perennial water shortage? To begin with, the government doesn't think that there is a water shortage at all. "The real problem is not shortage of water but inequitable distribution and ineffective management," claims Maken.

Assuming that the diagnosis is correct, this still leaves the government with the onerous task of setting the mess right. The Plan also talks about additional power requirement of 7,830 MW. Whether that would be enough to get rid of incessant power cuts is anybody's guess.

Parking

The MPD-2021 talks of solving the acute parking problem by utilising open spaces and constructing underground parking facilities. It suggests a provision of two equivalent car spaces (ECS) in plots of size 250-300 sq m on residential plots. The second proposal sounds fine on paper, but the ground reality is that this provision can be realistically implemented only in new housing projects and not in existing areas where there are no open spaces. What's more, clear-cut guidelines for underground parking are absent.

Waste disposal

Only about 55 per cent of Delhi's population is covered under organised sewerage. The Plan has attempted to address this issue. It projects that by 2021, the total waste produced in Delhi every day would go up to 15,750 tonnes per day. The Plan says that at least 10 garbage processing facilities will be provided. Besides, 15 acres of land has been proposed for the landfill sites.

But the numbers stop making sense when you find out that only 24 landfill sites have been listed in the Plan, out of which 16 are already filled up. Three out of four sites in operation are saturated and only four are currently available for disposal.

Regularising unauthorised colonies that contribute largely to untreated sewage might happen in a snap, but there will be a definite delay in laying down internal sewerage lines. Until that time, the Yamuna river will continue to get polluted.

All the planning in MPD-2021 has been done on the basis of projections of available land and a population target of 23 million. What if the population burgeons more than it's been assumed much like the way it happened with MPD-2001. As against the projected population of 12.8 million, the number surged to 13.8 million then. MPD-2021 suggests no alternate gameplan.

After analysing the proposals of MPD-2021, most of which seem impractical, it is not difficult to conclude that authorities are likely to trip once it comes to implementation. Sadly for the Delhiite, despite a plan of action for the future, he is unlikely to get much succour from the problems that plague his daily life.

Will the Delhi Master Plan Work?

Will the Delhi Master Plan 2021 live up to the billing given by its various votaries and its authors, the Delhi Development Authority and Ministry of Urban Development.

Outlook Money sought the views of Ajay Maken, Union Minister of State, Urban Development, to get a sense of the thoughts that guided the drafting of the document and KT Ravindran, urban designer and Dean of Studies, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi for a critique. Here's what they had to say:

**********

K T Ravindran, Urban Designer, Dean of Studies, School of Planning and Architecture:

Unplanned, mixed land use. The provision of mixed land use is an unplanned one. It will increase the load on infrastructure. The building typologies should evolve to accommodate the multiple functions without interfering with each other. The Master Plan is setting a bad example for other cities on two counts. First, it is being perceived as an instrument that will be used for short-term political gains.

Erroneous assumptions. Second, the document works on the assumption based on a certain amount of land available for a projected population of 23 million.

All other calculations are based on that figure. It doesn't realistically assess the thresholds of environmental sustainability.

Impaired vision. In my opinion, issues like water, disposal of sewage, solid waste, ground water conditions, must become thresholds of development, rather than just land. At the moment, the whole planning exercise is seen as a land management exercise.

**********

Ajay Maken, Union Minister of State for Urban Development:

Boost to housing supply. Almost 55-60 per cent of Delhi's population lives in unauthorised areas even when adequate land is available due to factors such as artificial restriction on the floor area ratio, keeping out private players from the housing sector and the notion that Delhi should not go high-rise. By 2021, there won't be any backlog as far as housing supply is concerned.

The redevelopment norms would lead to an additional 50 per cent dwelling units and still leave 66 per cent open green space.

Better amenities. By creating a vertically compact city (as the Master Plan envisages), there would be lesser transmission losses than now, and the problems related to power and water will be brought under control. I envisage a city that is slum-free, with adequate housing for all and an effective public transport system with lesser dependence on cars. The Plan will be reviewed every five years.