The year was 1999. The venue was Khyber Pass in north Delhi, named after the pass that connects Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Delhi Metro Rail Corporation Deputy Chief Engineer Daljeet Singh was taking charge of a piece of land where trucks used to be parked.

The truckers were angry. Some of them tried to set his car ablaze. In hindsight, it was a minor hiccup. Fourteen years later, Delhi Metro is all set to roll into Greater Noida in Uttar Pradesh and Bahadurgarh in Haryana.

Its network is already 190 km long. By 2021, it will have added another 240 km. Khyber Pass, where the truckers had shown murderous intent, has a Metro depot. And Singh holds no bitterness against the truckers.

Land acquisition, he says, was a new concept then. "When people's livelihood is affected they obviously protest, but they soon realise that it will help them."

Singh is not bitter because DMRC has gone from strength to strength, assuming a bigger role in Delhi's civic life. Last week, it was asked to draw up a blueprint to decongest and redevelop Chandni Chowk area in the old part of the city.

Property prices climb 5-10 per cent in localities touched by Delhi Metro. It is also widely recognised as an agent of social change: apart from other things, it helps the middle classes travel to protest venues in style and reasonable comfort.

In recent protests, the Delhi Police cleverly shut Metro stations close to the disturbances.

...

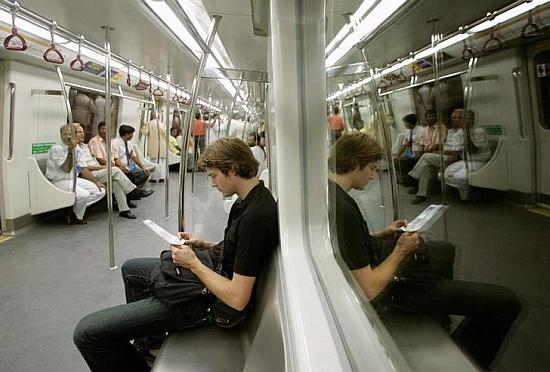

The bus corridor, which was projected as an inexpensive mass transport alternative to the Metro, is out of reckoning because of tardy traffic management. Over 1.8 million travel on Delhi Metro every day.

Elsewhere in the country, the Metro network hasn't grown as rapidly. Kolkata Metro became fully operational only in 1996 after a delay of a good 16 years.

Though it had begun services in October 1984, it covers only 25.2 km and ferries 600,000 people a day.

The plan is to extend it to 111 km by 2015-16 and raise the ridership to 2 million a day but, admit Kolkata Metro officials, the target is almost impossible to achieve.

In 2010-11 and 2011-12, Mamata Banerjee, the then Union railway minister, had allocated Rs 10,000 crore (Rs 100 billion) for Kolkata Metro's expansion. The money couldn't be utilised and was therefore diverted to other arms of the Railways.

Bangalore's Namma Metro, inaugurated in October 2011 on a small stretch connecting Baiyappanahalli in the east to MG Road, started operations after several postponements. Even after a year and three months of operations, it services the same 6.7 km.

At the time of the inauguration, it was hoped that the 42.3-kilometre Phase 1, consisting of an east-west corridor and a north-south corridor, would be ready by December 2013; it is now expected to be ready only by December 2014.

...

Construction of a crucial underground section has been held up by Dalit groups opposing the temporary relocation of a statue of B R Ambedkar from its place in front of Vidhan Soudha (a statue of Jawaharlal Nehru and another of Subhash Chandra Bose that were in the same area have been shifted), and the state government is waffling on the December 12 order of the Karnataka High Court to remove it within 15 days.

Aware that elections to the state legislative assembly are around the corner, the government's solution seems to be to separate the statue from its pedestal, and hang it in a cage that will be suspended from a crane, at the same spot. The wrangling over the issue has delayed construction by six to eight months.

In Mumbai, the story is no different. The Metro project here has seen a time overrun of two years.

Mumbai Metro One, a special-purpose vehicle created by Anil Ambani's Reliance Infrastructure to construct the 11.40-km link from Versova in western Mumbai to Ghatkopar in the east, blames land acquisition for it, even though one of its partners in the project is the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority.

A Reliance Infrastructure-led consortium also has the contract to build the 32-km second phase linking Charkop in the north to Mankhurd in the east but that project too has had problems with environmental and land clearances. The company is reportedly on the brink of losing the project.

...

In Hyderabad, thanks to problems over land acquisition and the Telengana agitation, the deadline for the completion of the 72-km project has been extended by two years to 2017.

Hyderabad Metro, mind you, has already lost two years: in 2008, Ramalinga Raju's Maytas Infrastructure had bagged the project but lost it after the Satyam scam broke in 2009 and the company couldn't achieve financial closure. In July 2010, the project was awarded to Larsen & Toubro.

In Jaipur, the Metro may run on a 9-km section by August only because Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot is pushing hard.

Elections to the state assembly will be held in November or December; Gehlot wants the Jaipur Metro to roll before the Election Commission's model code of conduct comes into force.

In Chennai, three-quarters of the civil works for the 45-km project has been completed, and trial runs could start by July.

Since Chennai Metro was started when DMK ruled the state, Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa (of AIADMK) has said her government will launch a monorail project next!

In cities like Pune, Lucknow, Nagpur and Ludhiana, the Metro hasn't even got off the drawing board. Amongst the smaller cities, work has begun only in Kochi.

How did Delhi Metro get it right? DMRC changed the way infrastructure projects were executed in the country.

All completion deadlines were met and there was minimal traffic disruption, though there were a few accidents.

...

Partly it came from the aura surrounding E Sreedharan, its first managing director, who took his own decisions and brooked little interference from both the central and state governments.

That helped in another way. "Completing the projects on time had a very positive impact on the Japanese government (which was funding the project). In the subsequent phases, we did not face difficulty in getting funds," says DMRC Managing Director Mangu Singh, Sreedharan's successor.

Most Metros say the real stumbling block is land acquisition. There are multiple owners and each wants the best price. Their biggest bugbear is acquisition of private land.

Singh does not buy the argument that Metros get delayed over land acquisition. In a Metro project, private land is minimal - hardly 5 per cent of the total. Most of the land required is either owned by the government or common areas like parks.

"It is true for all cities. So if you can construct 95 per cent, then 5 per cent should not be a problem. For good work, nobody puts a spoke. The initial reaction of people may be no but, increasingly, there is a realisation that it is in public interest."

DMRC's success is also about smart financial management. It had received a soft loan of Rs 16,000 crore (Rs 160 billion) from Japan for the first two phases (total project cost: Rs 30,500 crore or Rs 305 billion).

Though termed costly (Rs 163 crore per km in the first phase), Singh says project costs have been brought down by 10-15 per cent in the second phase and they will come down further in the third phase.

...

The cost of a Metro largely depends on what portion of the stretch runs underground - it is two-and-a-half times costlier than elevated tracks - and the number of stations.

The second phase was largely over-ground and, hence, cheaper. Besides, unlike the first phase when it had hired consultants, the company used its in-house project management expertise in the second phase.

Smaller contract packages too helped in more competitive bidding. With staff strength of 37 people a km, manpower management has helped keep operational cost low.

The company spends 0.52 paise on every rupee it earns. About 20 per cent of its daily revenue comes from non-operational sources like real estate.

Building extensions into Noida in Uttar Pradesh and Gurgaon and in Haryana are even cheaper since the cost of fixed infrastructure is borne by the state government as a grant and new depots are not needed.

DMRC's expenses are limited to purchase of rolling stock.

Not surprisingly, many other cities want to replicate the DMRC model; each time a project is conceived, the option of creating a government-sponsored organisation like DMRC, instead of contracting a private developer, is debated. (The Railways have invested only in Kolkata Metro.)

State governments want to associate with DMRC. The company is executing the first phase of Jaipur Metro and has started work on Kochi Metro as well.

Many in the Delhi government want it to even do the monorail project in the city. Singh of DMRC says private-public partnerships demand high viability-gap funding from the government, which doesn't make sense.

...

"We have prepared project reports in many cities. Sometimes it is as high as 80 per cent. There is no point in having public-private partnerships if the government has to give that much."

Delhi Metro's own experiment with such partnership had its share of problems. Reliance Infrastructure, which operates the 23-km Airport Express Line in Delhi, shut down the service for six months blaming shoddy civil works by DMRC.

The line reopened only in January after repairs. The private operator is currently locked in arbitration with DMRC. Singh says the line is not a true public-private partnership because the "major risks of construction were taken by DMRC".

Chennai has opted for the DMRC model. The Rs 14,600-crore (Rs 146 billion) metro project is being built through 41 per cent funding from the Centre and State governments, the balance is a loan from the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

In Hyderabad, in contrast, of the total cost of Rs 16,375 crore (Rs 163.75 billion), L&T is bringing in Rs 3,439 crore (Rs 34.39 billion) as equity, the largest commitment made by it in any single project at that point, while debt of Rs 11,478 crore (Rs 114.78 billion) has been sanctioned by a consortium of 10 banks led by State Bank of India.

The rest Rs 1,458 crore (Rs 14.58 billion) is viability gap funding from the centre. On the flip side, L&T doesn't have to share the revenue with the state government.

...

State governments need to weigh their options. Uttar Pradesh, for instance, has agreed to bankroll the new line to sparsely-populated Greater Noida, though it is still debating the viability of a Metro for Lucknow and Kanpur, old cities that desperately need their infrastructure to be renewed.

One reason could be the huge investments made by real estate developers in Greater Noida. One estimate suggests over 200,000 flats are being built there.

"In Greater Noida and Gurgaon, the builders want Metro to come up," says DMRC's Singh. The reasons are obvious.

In Jaipur, property prices in and around areas from where Metro will pass or operate have recently gone up. Surendra Rajpurohit, a property consultant in the city, says land prices have increased by 20-25 per cent.

Real estate prices in Garia and neighbouring areas in south Kolkata have sharply risen about 60 per cent since it was added to the Metro network about four years back compared to 30-40 per cent in other parts of the city.

That could provide the real push to Metros across the country.

(B Dasarath Reddy, T E Narasimhan, Indulekha Aravind, Anil Sharma and Probal Basak contributed to this article)