Photographs: Reuters Prasanto K Roy

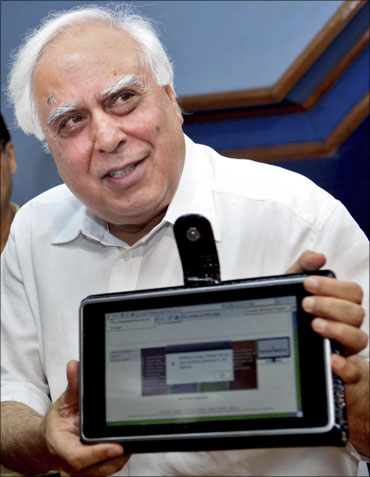

Here we go again. Indian Human Resource Development Minister Kapil Sibal has 'launched' a $35 computer, evidently his 'dream project'.

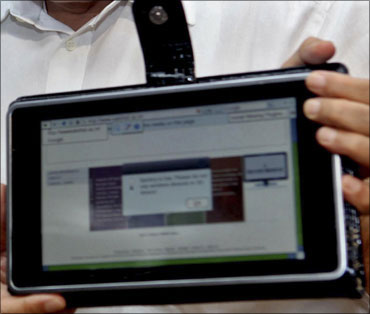

The touch-screen, Linux-based device looks iPad-inspired, but we know little about how it works.

It emerged from a student project with a bill of material adding up to $47, a price that the minister wants to bring down to $10 "to take forward inclusive education".

It promises browser and PDF reader, Wi-Fi, 2GB memory, USB, Open Office, and multimedia content viewers and interfaces.

Will it die a quick death within this year, or a painful, government-funded one over the next two? I fear the latter.

Project Sakshat even has a busy website so it looks like a project well under way.

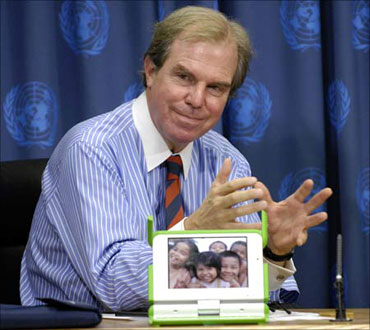

The Rs 10,000-personal computer. . . The Simputer. . . The $100 MIT laptop. . . NetPCs from a host of companies. . . India's so-called $10 laptop. . . How many flops and failures will it take to convince governments (and brave but misled companies) to get these facts of tech, products, and life?

You don't launch products until you have a product to launch. Else it is vaporware. The Indian government is building up a good track record of vaporware, from $10 laptops upward. (Apple launches with a million units ready to sell, and midnight queues outside.)

. . .

Why India's $30-laptop joke isn't funny anymore

Image: Human Resource Development Minister Kapil Sibal displays the low-cost computing device during its unveiling in New Delhi.Photographs: Reuters

You don't show prototypes unless they are working ones with running apps, backed by a clear game plan to build up a vendor and apps network, and a clear design, spec (and preferably bill of materials).

It isn't about the hardware. It's the application and the apps ecosystem. What will it be used for, and who will make those apps? Where's the developer community and the roadmap for hundreds of apps, as Apple had when it launched the iPhone and the iPad?

Product design isn't a one-off procedure. It's an ongoing process, with software updates, improvements, upgrades, and most of all, growing apps support.

You can make a working laptop, but it's no trivial task maintaining it through the life-cycle of the product, ensuring support, firmware and hardware upgrades, and new versions.

Replicating the Tata Nano story is no joke. It takes years, expertise, innovation, hard work and lots of luck (and many patents, as with the Nano) to launch a product at one-tenth the current market price.

I don't know of any examples of such overnight miracles (the Nano arrived after years of work, at about half of the current entry-level product's price tag.)

You don't re-invent the wheel. We already have $35 computing devices. We call them mobile phones. They're capable, connected, always-on, personal, and every second Indian has one.

They're an ideal front-end to information and entertainment, served over voice or SMS or data.

. . .

Why India's $30-laptop joke isn't funny

Image: Nicholas Negroponte, shows a model of the $100 laptop computer he developed for the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) non-profit group.Photographs: Chip East/Reuters

Over the years I've been less blunt about cheap-PC efforts. But now I am angry. The government is wasting its efforts and my tax money, and making a laughing stock of Indian technological prowess.

It isn't the government's job to create and sell cheap PCs.

If it wants to use ICT for development and education, it can use some of our tax rupees to build the ecosystem. Create compelling G2C (government to citizen) apps. Shift to education delivered over networks, make e-tax filings mandatory, create citizen services delivered over the Internet . . .

And ramp up tech usage in the government. Ensure employees have broadband at home, with reasons to use it -- intranets and work-from-home -- as well as mobile data and apps.

Oh, and it can use the funds and roadmap of the Sakshat project to fund content development for $35 mobile phones -- of which there must be 100 million in India.

This isn't the first 'cheap laptop' effort. MIT's $100 laptop hasn't taken off yet, though it's at the $200 level currently and has a roadmap -- including options to fund a subsidy.

And maybe Sakshat 2.0 is not a hoax, unlike its predecessor. Yes, you can reach any price with sufficient subsidy. But that is no enduring solution. It may make more sense for India negotiate a rock-bottom price for 10 million of last year's laptops, and subsidize them down to $35.

Prasanto K Roy, chief editor of CyberMedia's ICT publications group.

article