Photographs: Reuters Rajni Bakshi

Many people who recognise the grave implications of climate change find it difficult to grapple with it. The problem is too big and thinking about it can be unbearable, says Rajni Bakshi.

'System change not climate change' may be the most evocative slogan by protestors who have gathered outside the annual UN climate summit now underway at Durban.

'The system isn't broken, it was built this way,' said one banner at one of the many rallies that have been held by activists from across the world.

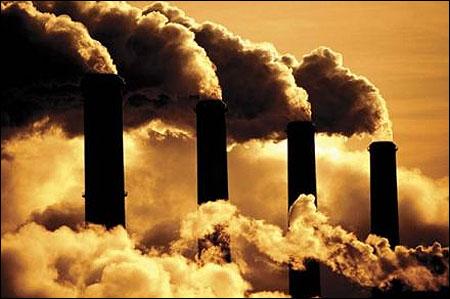

Inside conference halls, the richest nations -- who are also the largest emitters of green house gases -- are reportedly working to kill the Kyoto protocol. Unless the protocol is renewed it will expire in 2012.

Effectively this could mean that there may be no globally agreed framework for a significant and rapid reduction of greenhouse gases. This in turn would drastically increase the chances of catastrophic climate change over the next few decades.

Ironically, the top story of the last week in India has been FDI in retail. That is because both its advocates and its opponents claim that the future of the Indian economy is at stake. But the implications of runaway climate change are incalculably greater.

. . .

Wanted: System change not climate change

Photographs: Reuters

In 2010, out of the 950 natural disasters reported, 90 per cent were weather-related. These disasters cost the global community $130 billion.

Even then, climate change has fallen off the front pages of most newspapers and not just in India. For example, on BBC's website the Durban conference is being covered in the science and technology section, not as a top story.

This is partly because 'climate change deniers', those who claim that projections about human induced climate change are exaggerated, have had a substantial impact on the global media in the last few years.

Many people who recognise the grave implications of climate change find it difficult to grapple with it in their day to day lives. The problem is too big and thinking about it can become unbearable.

And yet the protests at Durban are a reminder about the wide range of people, across the world, who are engaged in highlighting the problem and campaigning for solutions.

. . .

Wanted: System change not climate change

Photographs: Reuters

'Climate Justice' is the term around which much of this mobilisation is happening.

In South Africa the call for climate justice is particularly poignant. Patrick Bond, director of the Centre for Civil Society at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, said in an interview last week that this campaign has created more hope politically than anything since the end of apartheid.

"The struggle for action on climate change is incomparable to any other struggle that we have seen," said Kumi Naidoo, executive director of Greenpeace.

"Other struggles have affected one country -- or maybe a group of countries -- but climate change affects every single human being on the planet."

The objective of these mostly decentralised but globally pervasive campaigns is what journalist and activist Praful Bidwai has called 'FAB' -- a Fair, Ambitious and (legally) Binding global agreement that would ensure both justice between rich and poor countries while adopting an emergency programme to reduce emissions drastically.

. . .

Wanted: System change not climate change

Photographs: Reuters

Bidwai's book, The Politics of Climate Change and the Global Crisis: Mortgaging Our Future, was released last week. In this book Bidwai outlines the following points as the 'highest achievable result' possible out of the Durban meeting.

- An agreement on a second commitment period for the Kyoto protocol with an ambition to make global emissions peak well before 2020 and fall by about 20 per cent by that year in an equitable manner.

- At present various countries have put conditions on their pledges to undertake mitigation measures. These conditions should be removed and targets must be set for reducing emissions.

- Agreement is reached on mobilisation of substantial finance for adaptation, mitigation and low-carbon development -- that is deliverable within a democratic governance structure.

These are ambitious goals. Cutting global emissions by 25 per cent by the year 2020 is probably the toughest collective challenge ever faced by the nations of the world.

. . .

Wanted: System change not climate change

Photographs: Reuters

It is made harder by the fact that the political climate in the United States of America and Canada is hostile to what is being asked of them -- namely a 40 per cent reduction of emissions by 2020.

Moreover, the top leadership in many key countries, including India, is perceived to have put these matters in the background.

As if this were not daunting enough the concluding lines of Bidwai's book set the bar even higher: "In the last analysis, combating climate change is not about tinkering at the margins -- by promoting some windmills and solar power stations, or imposing peripheral climate-related or 'green' obligations upon businesses, or even encouraging them to be ethical. It is about transforming the existing relations of power, overhauling the entire way in which humanity consumes natural resources to produce goods and services, and bringing about change, not of degree, but of kind."

Thus the slogans in favour of 'system change' at Durban and countless other protest sites across the world. No claims are being made about the potential of such civic mobilisation to actually change the course of events.

But after the events of this past year, from Tahrir Square to Occupy Wall Street, there is a renewed energy and hope at such gatherings.

article