His innovation to churn out low-cost sanitary napkins is a double boon to poor women of rural India: they can lead a hygienic lifestyle and it helps them earn a living too!

Forty-seven-year-old A Muruganantham does not like to call himself a businessman. The company he has started, Jayashree Industries, supplies machines and raw material for making sanitary napkins. The difference is that his machines go only to poor women in the rural areas.

There are already 250 machines installed in 18 states in India.

Last year, President Pratibha Patil presented the National Innovation Foundation's 'Fifth National Grassroots Technological Innovations and Traditional Knowledge Award' to him in New Delhi.

His machine was chosen by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to be deployed in Africa. Though a school dropout, the success of his innovation has enabled him to go to IIM-Ahmedabad as a visiting professor and talk about his work. He was one of the speakers at the TiE (The Indus Entrepreneurs) conference too.

He spoke to rediff.com on his innovation and future plans.

Tough childhood days

My father was a handloom weaver and my mother, a farm labourer. There was no question of me dreaming about being an entrepreneur.

But my mind was always active with ideas and I wanted to be an inventor.

When my father died in an accident, the financial condition of my family worsened. My mother's meagre earnings -- Rs 7 daily -- was all we had for food and schooling.

I was forced to drop out of school when I was in the 10th standard. I stared working in workshops as a helper. I preferred workshops because I was always fascinated by machines. I earned Rs 2 a week!

Life went on like that, and I didn't even know how I grew up.

...

If you wish to contact him, please write to him at muruganantham_in@yahoo.com or visit www.newinventions.in

How sanitary napkins became an obsession in his life

One day I saw my wife walk past me hiding something. I enquired what was it. . . but she evaded me, saying it was none of my business.

When I insisted I found she was carrying a piece of cloth that was dirtier than the rag I used in the workshop. I was horrified to learn that she would use it for personal hygiene during her menstrual cycle. Here was a woman who had studied up to Plus 2 (Class 12) and was behaving like an illiterate woman!

She told me she was aware of sanitary napkins, but if all the adult women in the house used them then they would have no money to buy food.

I had no idea that they were so expensive. As a matter of fact I had absolutely no idea about the whole issue -- what they looked like, why women need them -- nothing.

I went to a store and bought a packet. I found 10gm cotton in each napkin. It should not have cost more than 10 paise, but was actually selling for Rs 3.

I wondered why I could not make it affordable for poor women, like my wife and sisters.

I bought a good piece of cotton cloth and cotton, made a very simple napkin and asked my wife to be a volunteer. Unfortunately, all three -- my wife and my two sisters -- refused.

I tried an experiment by filling a football bladder with animal blood that I collected from a butcher's shop. It proved completely useless.

I then went to the Medical College which was around 28 kms away from my village, and requested some students to be my volunteers, and they agreed. But their feedback was negative. They were not satisfied with my product.

I was so obsessed, the women folk of my house thought I had gone mad and become a pervert, and they left the house calling me, 'mental' and 'psycho'!

Those were the first accolades I got! But I was unperturbed. I was only obsessed with the thought about why my napkins didn't work.

...

Mystery solved; it's not cotton!

In the meantime, I had sent the branded napkins to various labs to test what was inside, and the verdict was: cellulose.

I was told that the cellulose used in the napkins would be available in the United States.

I took the help of a college professor to draft a letter to the manufacturer to see the sample material. As you know, I, a school dropout, didn't know enough English and couldn't draft a formal letter.

What came to me from the US was a small parcel with ten cardboard sheets. I was puzzled.

Only after ten days, when I tore open one sheet that I realised that fibre from pine wood was what was inside, and that was what was used in sanitary napkins.

I also found out that you needed a machine to make cellulose out of wood fibre. Cotton absorbs fluid but does not retain it while cellulose, both, absorbs and retains it.

Once I learnt the mystery behind the napkins, I searched for the machine. To my horror, I found it cost Rs 4.5 crore (Rs 45 million).

...

Machine to produce sanitary napkins designed

That was when I decided to design one. It took me around two years to design a machine that could process cellulose and make sanitary napkins. It was by trial-and-error that I reached the final product in 2005.

But I never looked at what I did as a business model because I knew I would never be able to compete with the multi-national giants.

I gave the material and machine to the women in my house so that they could have cheaper napkins to use. There was enough raw material for five years. But after two months, when they asked me for more raw material, I was shocked.

They told me they sold the napkins to the women in the neighbourhood, that too not as packets but as single ones.

97% of rural women do not use sanitary napkins

Let me quote you some statistics. As per a government study, only 7 per cent of India's female population uses napkins and that includes urban women too.

In rural areas, only 3 per cent use. That means 97 per cent of rural women do not use napkins. Why do they not use it? Because of two reasons: availability and affordability. Then I hit upon an idea.

Why not give the machine to rural women so that they could make cheaper napkins? The result would be both easier availability and affordability.

...

Award from IIT- Madras

In 2006, when I approached the Indian Institute of Technology-Madras to evaluate my machine, I was told to send in all the details.

I did not know that they had included my innovation in the competition that was held at that time on Best Innovation for the betterment of society. My machine was chosen as the best innovation from 689 entries.

The news appeared in all the newspapers and local TV. Soon I started getting orders for the machine but I had no plan to sell it for commercial purposes. I know what suffering is and I wanted in some way or the other to be useful to the society.

Machines only to poor rural women

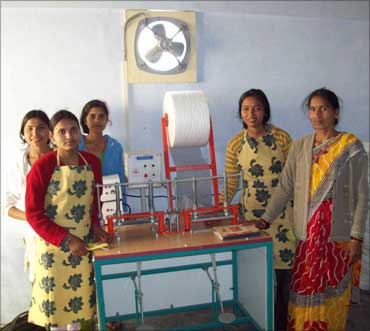

I decided to supply my machine only through DRDO or a self-help group to the poor women in rural areas. I have sold 250 machines till now, and they are spread all over India, in the rural areas of 18 states.

All the machines are operated only by the poorest women in the villages. My job does not end with supplying the machine; I myself go and train them to operate the machine.

I don't supply it to any government as no government is interested in the betterment of people.

...

Future plans

In the next one-and-a-half years, I want to supply 20,000 machines. I started selling them at Rs 47,000 but now, the price has gone up to Rs 80,000, and that included 12.5 per cent tax.

To set up a machine with raw material, it would cost Rs 150,000. In most places, the SHGs arrange for bank loans.

Unlike the MNCs who make napkins in one place and transport to various areas, these women make napkins and sell in that area alone. From each machine, you can make 1,000 pieces a day and a minimum of 25,000 pieces a month.

The Union government is now talking about supplying free napkins to women by spending Rs 200 crore (Rs 2 billion).

With the same amount, we can create 100,000 units across India and each unit can have 10 women working in it. This way, we create employment for a million women.

Think of those poor women in Bihar, the beedi workers of Sivakasi and many such places. I am interested only in employment generation and women moving from unhygienic rags to using napkins. We also teach the women hygiene and ways to dispose of the napkins.

...

Recognition from MIT, IIM-A

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US bought my machine for African countries. The condition of African women is no different from ours.

I am happy that the world's premier institute found my innovation worth recommending. I am also getting enquiries from Kenya, Ethiopia, and Nigeria. This will be useful to women residing in Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka too.

Being a non-business person, I am going to transfer the technology which I have patented to the African countries as I have no plans to sell my machines there.

I was invited to speak at the TiE (The Indus Entrepreneurs) meet in Mumbai in 2009. I asked the elite crowd, "When a school dropout from a small place in Coimbatore can think of making his innovation useful to society, why don't you educated people think on these lines?"

The Indian Institute of Management-Ahmedabad, and other business schools and engineering colleges, invited me as a guest professor.

I ask them, "Are you trying to survive in this world by accepting a job that offers you crores of rupees or are you trying to achieve something?"

I am proud to say that quite a few were disturbed by my question.

I believe that the quality of your work is more important than money. Money has to be a by-product, not the aim.

...

Award from the President of India

Last year, President Pratibha Patil presented the National Innovation Foundation's 'Fifth National Grassroots Technological Innovations and Traditional Knowledge Awards' to me.

I must say I never aimed for any award; they are just by-products. Awards help me take my product to the targetted audience.

I am not a businessman. I also don't like to say that I am a social entrepreneur though many use that word to describe me. I am not serving society; I do what I like and what I enjoy doing. I only want to be a job provider.

The biggest award I got was from a woman from Uttaranchal who told me, "Bhaiyya, I admitted my daughter in a school!"

A woman from such a far-off place called me bhaiyya, her brother. She could put her daughter in school only because of the money she made by selling napkins. Her words were the biggest award I have ever won!