Photographs: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Reuters Shankar Acharya

The choice before India is not whether to urbanise or not, but rather between reasonably planned, efficient, growth- and employment-enhancing urbanisation, and the higgledy-piggledy expansion of congested, polluted, under-serviced and unhealthy urban sprawl, feels Shankar Acharya

Halfway through its 40-page manifesto, the Bharatiya Janata Party -- the likely anchor of a new coalition government -- identifies ‘urban areas’ as ‘high growth centres’ for India’s development and promises to build ‘100 new cities’.

The identification of good urban policies as prerequisites for rapid economic and social development is sound: two-thirds of national gross domestic product comes from urban India.

The apparent focus on new cities is not.

What India needs is not a whole lot of very costly, brand new cities but a revamping of urban institutional structures and policies to improve the obvious squalor and inefficiencies of the country’s existing 8,000 cities and towns.

. . .

What actually plagues India's cities

Image: A general view of the residential apartments is pictured at Gurgaon, on the outskirts of New Delhi.Photographs: Parivartan Sharma/Reuters

The BJP’s brain trust on economic and social policies would do well to read three good new books on Indian urbanisation that have been published over the last two months: Transforming Our Cities, by Isher Judge Ahluwalia (Harper Collins); Urbanisation in India, edited by Isher Judge Ahluwalia, Ravi Kanbur and P K Mohanty (Sage); and Cities and Public Policy, by P K Mohanty (Sage).

They could start with Dr Ahluwalia’s highly readable and engaging introductory chapter to her book.

In this brief column, I rely heavily on these recent books to give some flavour of the major issues and challenges that India faces as her urbanisation proceeds.

. . .

What actually plagues India's cities

Image: Traffic moves during the evening as the Howrah Bridge is lit up in the background in Kolkata.Photographs: Jayanta Shaw/Reuters

And proceed it will, since the shift from rural to urban habitation is an intrinsic dimension of the larger process of economic development and structural change experienced by all major nations.

As incomes rise, the relative role of agriculture shrinks, while those of industry and services rise.

And, the world over, these non-agricultural activities of industry and services prosper best in urban areas, which nurture the economies and efficiencies of scale, scope and connectedness (the so-called benefits of agglomeration).

The choice before India is not whether to urbanise or not, but rather between reasonably planned, efficient, growth- and employment-enhancing urbanisation, and the higgledy-piggledy expansion of congested, polluted, under-serviced and unhealthy urban sprawl that is so typical of today’s Indian urban landscape, and so damaging to India’s long-term development prospects.

. . .

What actually plagues India's cities

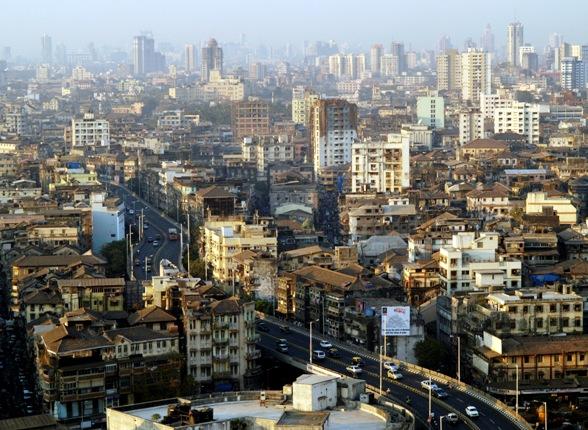

Image: Actually, the pace of India's urbanisation has been slow by international standards.Photographs: Reuters

Some dimensions of the challenge

Actually, the pace of India’s urbanisation has been slow by international standards.

According to census and United Nations data, India’s share of urban population in 2011 was 31 per cent, compared to around 50 per cent in China, Indonesia and Nigeria, 61 per cent in South Africa, 78 per cent in Mexico, and 87 per cent in Brazil.

In the 60 years from 1950 to 2011, India’s urban population share rose from 17 per cent to 31 per cent, while China’s quadrupled from 12 per cent to 49 per cent.

Nevertheless, the number of people involved is large: in the 20 years from 1991 to 2011, India’s urban population rose to 377 million -- 160 million more than in 1991 and 90 million more than in 2001.

By 2031 the urban population is projected to increase by more than 200 million to 600 million, or 40 per cent of the national population.

. . .

What actually plagues India's cities

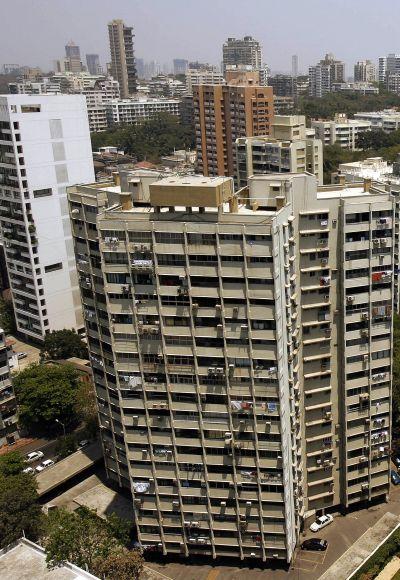

Image: The condition of urban communities and their services in India is woefully inadequate.Photographs: Reuters

Despite India’s relatively low level and pace of urbanisation (by international standards), the condition of urban communities and their services in India is woefully inadequate. Consider the following:

- Twenty-five per cent of urban India dwells in slums; in Greater Mumbai the ratio is over 50 per cent.

- Barring a couple of small towns in Maharashtra, no city provides continuous piped water.

And the water that does come, fitfully, is rarely fit to drink without boiling or other treatment.

In contrast, cities in China and Brazil get much better water 24x7. - Very few Indian towns (such as Chandigarh, Navi Mumbai and Surat) treat over 90 per cent of their sewage (excrement and waste water) before discharge into rivers, sea and lakes.

In the vast majority of urban communities, the treatment rate was far lower, well below 50 per cent.

Until recently it was 30 per cent in Delhi, and has now increased to 50 per cent. - Urban India is estimated to produce 180,000 tonnes of garbage every day, most of which ends up in huge rubbish heaps or ‘landhills’, instead of being composted, converted to energy or sealed in sanitary landfills.

Overflowing garbage bins and rubbish heaps are common sights. - Little wonder that diseases like dengue, malaria, typhoid, swine flu, diarrhoea and respiratory ailments are on the rise in most towns in India.

- Urban road systems are grossly inadequate and poorly maintained.

Typically, public transport is scarce: only about 500 out of 8,000 cities and towns have a public bus system.

. . .

What actually plagues India's cities

Image: The institutional framework for urbanisation in India has been historically weak.Photographs: Reuters

The way forward

At the heart of the quality of urbanisation is the governance system of institutions and policies that guide and oversee the planning, execution and co-ordination of land use, building regulations, road construction and delivery of key services such as water supply, sanitation, transport, and solid waste disposal, while ensuring adequate mobilisation of the necessary financial resources.

The institutional framework for urbanisation in India has been historically weak. Significant improvement occurred in 1992 through the 74th Amendment to the Constitution, which emphasised the importance of urban local bodies.

But many believe that this matter needs to be revisited to assign better revenue resources to ULBs, clarify expenditure responsibilities in relation to state and central governments, and improve their staffing and competencies.

. . .

What actually plagues India's cities

Image: Labourers work at a construction site of a commercial complex in Mumbai.Photographs: Vivek Prakash/Reuters

Such systemic reform may well be necessary.

But a great deal can be accomplished within the existing framework, with strong administrative and legal support from state governments and some assistance from the Centre, as through the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission.

First, it is surely shocking that while over 2,000 new areas were designated as ‘towns’ by census enumerators (according to established criteria of population, density and employment in non-agriculture pursuits) between 2001 and 2011, the number of towns with statutory ULBs increased by less than 250.

Thus, a very large number of small towns do not have a ULB to deliver the basic services necessary in order to avail the benefits of agglomeration.

The facilitation of new ULBs is surely a primary task of state governments, with some assistance from the Centre.

. . .

What actually plagues India's cities

Image: Labourers work at the construction site of a commercial complex in New Delhi.Photographs: Anindito Mukherjee/Reuters

Second, ULBs are chronically short of resources.

Yet within the existing framework, many of them, especially city municipalities, could do a far better job in exploiting existing revenue bases such as the property tax.

International comparisons show that Indian cities are unusually deficient in raising revenue from property taxes, usually the prime source of income for urban local governments worldwide.

Indeed, as Dr Mohanty spells out, there is a range of other revenue instruments that could be deployed for harnessing some of the soaring land values in urban locales to fund the necessary urban infrastructure.

Third, user charges need to play a bigger role to fund provision of services such as water, electricity, bus services and waste disposal.

Fourth, as Dr Ahluwalia shows, ULBs can improve -- and have improved -- resource mobilisation and service provision through intelligent deployment of information technology.

. . .

What actually plagues India's cities

Image: Well-functioning urban institutions and sound policies will nurture faster economic growth.Photographs: Reuters

More generally, there is a great deal that India’s urban governments can learn from each other.

Dr Ahluwalia documents some 40 case studies of progress in urban service provision. Not all of them are replicable or scalable.

But quite a few surely are, especially with the support of state governments.

The basic point is simple.

Well-functioning urban institutions and sound policies will nurture faster economic growth and more employment for the cities as well as the nation.

Continued neglect of urban governance and policies could cost the nation dearly.

And the focus has to be on India’s 8,000 existing cities and towns, not on a few dozen costly new showpieces.

Shankar Acharya is honorary professor at Icrier and former chief economic adviser to the government of India. These views are personal

. . .

article