India's macroeconomic condition remains quite shaky and certainly does not warrant an iota of complacency, rues Shankar Acharya

Hardly six weeks ago a sense of grim crisis pervaded India's economic policy-making circles and much of the public at large.

The underlying causes are well known: the post-2011 collapse of growth and investor confidence, major problems in the infrastructure and energy sectors, persistently high inflation, shrinking job opportunities, and large fiscal and external account deficits.

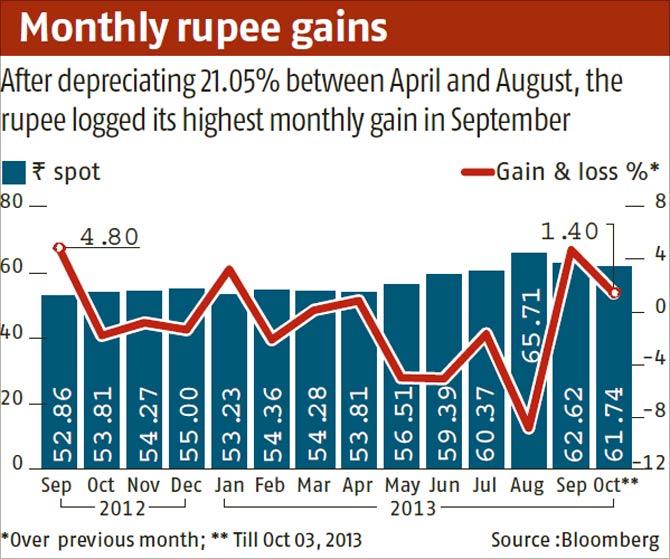

The alarm bell that had most strongly signalled (and reflected) the onset of economic crisis was the plummeting value of the rupee, which had dropped from 53-54 to the US dollar in May to nearly 69 by end-August.

The rupee's free fall had occurred despite a wide range of measures to reduce gold imports, restrict external payments and drastically tighten monetary policy.

The tide began to turn in early September with the new Reserve Bank of India governor's confident and well-considered initial policy statement on September 4, including the announcement of swap facilities to banks for foreign currency non-resident (bank), or FCNR (B), deposits with maturity of three years and over at a rate of 3.5 per cent per year.

. . .

This quasi-exchange rate guarantee soon triggered fresh inflows.

Within days of this initiative, wobbles in the US economic recovery suggested possible postponement of the US Federal Reserve's pre-announced intentions of "tapering" its monthly quantitative easing liquidity injections, a likelihood that was duly fulfilled by the Fed's September 18 announcement and restored a "risk-on" posture towards emerging markets. India's July and August trade data were also encouraging.

Together, these developments ensured a significant recovery in the foreign exchange and capital markets, with the rupee climbing back to the 62-63 range to the dollar by September 20.

As the currency and financial markets recovered, the sense of crisis and urgency dissipated swiftly.

By early October senior government officials were reportedly exuding confidence that the currency turbulence was over, that the 2013-14 current account deficit would be held below $70 billion (around 3.7 per cent of gross domestic product, or GDP) thanks to a sharp decline in legal gold imports (August onwards) and some recovery in exports; that the Centre's fiscal deficit would not cross the "red line" of the budgeted 4.8 per cent of GDP; and that economic growth would recover to average about 5.5 per cent of GDP for the full year, despite the 4.4 per cent rate recorded in the June quarter.

Confidence is certainly commendable, but when does it shade into complacency? Let us consider the realism of these official macroeconomic expectations.

. . .

If the sharp decline in gold imports in recent weeks persists, it would certainly help scale back the current account deficit.

A significant question is: how much has this decline in gold imports through official channels been substituted by an increase in smuggled gold?

As we know from the high levels of smuggled imports in the pre-1990 era, these are typically associated with financing arrangements that tend to reduce the recorded levels of invisible earnings and capital inflows, thus offsetting the apparent gain in the trade deficit.

Another major imponderable is the impact of the ongoing US government shutdown and possible failure to raise the debt ceiling.

On the one hand, such uncertainties are likely to prolong current levels of QE and, thus, ease the financing of India's current account deficit. On the other, a significant setback to US and global economic activity could damp exports of goods and services and reignite global financial turmoil.

It is impossible to assess the net effects on India's external accounts at this stage.

. . .

The government's expectation of 5.5 per cent growth this year looks decidedly optimistic.

Aside from a good, monsoon-propelled performance in agriculture (which accounts for only 15 per cent of India's GDP) and a modest recent uptick in some core sectors (from depressed levels) and some exports, it is hard to locate signs of a significant resurgence in economic activity.

On the contrary, various business surveys (such as by CII-ASCON) point to industry continuing in the doldrums.

Major sub-sectors such as automobiles, consumer durables, textiles and construction remain in negative territory. Perhaps more significantly, the latest HSBC Purchasing Managers' Index data for September show a sharp contraction in the hugely important services sector, with the index falling below 45 (index values below 50 indicate negative growth outlook).

The PMI for manufacturing and services combined fell to 46, the lowest level in four and a half years. It is hardly surprising that the projections by foreign and domestic financial institutions (including the International Monetary Fund) cluster in the range of four to 4.5 per cent growth in 2013-14 - that is, even lower than in the previous year, and the lowest in 11 years.

The most implausible element in the finance ministry's present confident/complacent macro expectations pertains to the fiscal deficit target of 4.8 per cent of GDP.

As we know from the recently published fiscal accounts for August, the fiscal deficit in the first five months of the year already accounted for 75 per cent of the full-year target.

In contrast, tax revenues were just over 20 per cent of the yearly total, while non-debt capital receipts (mainly from disinvestment) were less than 10 per cent.

. . .

There is little prospect of huge buoyancy in these receipts in the second half of the year.

On the expenditure side, subsidies will overshoot significantly because of higher rupee prices for oil and fertiliser imports, unless prices are raised soon.

Two or three weeks ago, there were strong rumours about a Rs 4-5/litre increase in diesel prices. But these have subsided, and such price rises look increasingly improbable with major state elections due next month and the general elections by May.

For similar reasons the sharp curtailment of other budgeted expenditures of the kind done last year looks much less feasible this year.

In sum, the fiscal deficit could be overshot by a significant margin by the time the fiscal year ends.

In the first five months of 2013-14, the Centre's fiscal deficit ratio has been running at a whopping 8.7 per cent of GDP. Bringing it down to 4.8 per cent in the remaining seven months looks impossibly difficult, without recourse to seriously creative accounting ploys.

In any case, it is worth pointing out that a deficit that stays high through most of the year imposes the associated costs of higher inflation, higher interest rates, more crowding out of private investment and greater pressure on the current account deficit during the period, even if "miraculously" corrected in the final months.

It is also worth emphasising that if the months unfold without any serious policies to correct the deficit, there is a growing risk of negative external perceptions (including a possible credit rating downgrade), which could have serious adverse consequences for external financing of the current account deficit and for currency markets.

In other words, India's macroeconomic condition remains quite shaky and certainly does not warrant an iota of complacency.

This is doubly true if one considers the available patchy data on employment trends, which point to miserable job prospects for the country's burgeoning youth population.

Shankar Acharya is honorary professor at Icrier and former chief economic adviser to the Government of India. Views are personal