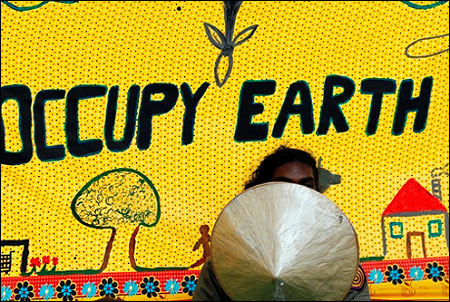

Durban will create climate apartheid, under which rich polluters evade responsibility, but underprivileged people suffer the worst effects of climate change for which they are least responsible, writes Praful Bidwai.

India's corporate media isn't known for professional treatment of news relevant to society. But never before has it so blatantly blacked out or distorted a major international event as it did the climate conference at Durban, South Africa, under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. It declared it a historic success, a victory for climate equity, and a triumph for India.

In reality, Durban was a disaster for global climate protection and the survival of millions of poor and vulnerable Indians. One didn't have to be physically present at Durban, as I was, to say this. It's obvious from public documents.

Durban was the world's last chance to make global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions peak in this decade, and breathe new life into the sole legally binding climate agreement, the Kyoto Protocol, beyond 2012, when its first phase ends.

Only thus could catastrophic climate change be averted and global warming limited to the 1.5-to-20 Celsius (over preindustrial temperatures) ceiling that Planet Earth can tolerate.

That chance has been lost. The world is now on course to 3-to-4 degree C, perhaps 5 degree C, warming by this century's end, if not earlier. Such a warmer earth won't be the same planet anymore.

At 3degree, many "tipping points" will be crossed beyond which the climate system changes irreversibly, and remedial action becomes useless. At 4 degree, say scientists, only one-tenth of the world's population may survive.

Click on NEXT for more...

Durban will create climate apartheid, under which rich polluters evade responsibility, but underprivileged people suffer the worst effects of climate change for which they are least responsible.

Consider the contrast between media reports and reality. The media says India forced a "climate breakthrough" and "regained its position as the ... moral voice of the developing world". It quotes environment minister Jayanthi Natarajan: "[W]e got the extension of Kyoto Protocol ...and restored equity as a central dimension of the debate. We firmly reiterated the right of ... developing countries to ...growth under the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities [CBDR]...".

CBDR holds that all countries have a common climate protection responsibility, but: rich industrialised countries of the North, responsible for three-fourths of accumulated atmospheric emissions, must do more, and do it first.

However, the key conference outcome, "the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action", does not even mention equity or CBDR. The Northern countries wanted an altogether different regime from that defined by the 1992 climate Convention, the Kyoto Protocol and the Bali Action Plan (2007), which created a firewall between the North's obligations and the South's voluntary actions.

A CBDR mention, they insisted, must be qualified by mandating its interpretation based on "contemporary economic realities", including recent North-to-South power shifts, and China and India's emergence as among the world's top five emitters. This would have opened a Pandora's Box.

At Durban, the Kyoto Protocol did not get its second "commitment period" (CP2), or post-2012 effective phase. The decision was postponed to next year's climate conference, without clarity on the North's commitments to higher ambition or equity.

Such commitments seem highly unlikely given past experience, and the Great Recession. The Protocol will turn into a soulless "zombie" until replaced by a new agreement that's even weaker.

Click on NEXT for more...

At Durban, developing countries didn't forge new solidarity, nor did "emerging" India become their "moral voice". They further split, with the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the least developed countries (LDCs), allying with the European Union.

Some of them expressed resentment at the insistence of the two-year-old BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India, China) grouping on "the right to develop". "While they develop, we die," little Grenada's ambassador said.

Durban failed to mobilise adequate emissions-reductions ambition, with 40-45 percent cuts by the North by 2020 over 1990.

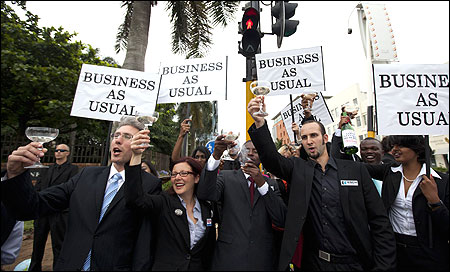

The biggest gainers are the North's fossil fuel-driven industries. The biggest losers are underprivileged people, especially in the LDCs and Africa - and the prospect of a fair, ambitious and binding agreement, based on science and equity.

Under "the Durban Platform", countries will negotiate by 2015 "a protocol, another legal instrument, or an agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all", to be implemented from 2020 onwards.

The tortuous wording of the last phrase reflects India's reluctance to accept binding commitments, and leaves the legal form somewhat open to interpretation. But postponing deep emissions cuts to 2020 will aggravate both climate change and the global developmental crisis. The longer the North delays cuts, the smaller the South's room for manoeuvre.

The Platform resulted from bad compromises imposed by the North on BASIC. The EU shifted the goalposts. Instead of unconditional support for a CP2 for Kyoto, it demanded that all nations accept binding reductions in a new deal.

This alone would bring the US, the world's greatest emitter which never ratified Kyoto, into the obligations net. The real reason was growing domestic climate pessimism amidst a massive economic crisis in the EU. The EU further its climate ambition under the presidency of fossil fuel-addicted Poland.

Click on NEXT for more...

Instead of mounting political-diplomatic pressure on states opposed to a Kyoto CP2, the EU-led negotiating bloc isolated and divided BASIC. BASIC's differences widened. South Africa and Brazil were willing to accept binding commitments, but not China and India. South Africa as the conference host, was keen to declare it a success by supporting the EU-led bloc.

At Durban, China indicated "flexibility" by offering to accept binding commitments on conditions, including a Kyoto CP2 covering all Northern emitters, higher ambition and transparency, pledges not to shift the climate burden from the North to the South, immediate activation of the promised $100 billion Green Climate Fund for developing countries, and rejecting binding obligations until 2020. These conditions were unlikely to be fulfilled. But they highlighted China-India differences.

India was seen as inflexible and got isolated. India failed to anticipate the EU's attempt to win over the most vulnerable and poorest of developing countries through financial promises, coercion and threats, similar to those used at the 2009 Copenhagen conference to secure adherence to the so-called Copenhagen Accord. WikiLeaks disclosed this.

The Copenhagen Accord was a collusive agreement between the world's greatest historical polluter, the US, and its biggest current and future emitters: BASIC. It was not officially adopted or endorsed. But it came to prevail and shifted the climate stabilisation burden from North to South.

In Durban's final session, there was much wrangling over the phrase, "agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention".

The US backed this - probably because it was the last chance to push China into binding commitments. Indian negotiators claim that the formulation means that the obligations must be in keeping with the Convention's principles, including CBDR.

Click on NEXT for more...

However, the Durban political context, with sharp divisions over CBDR's application and lack of a central differentiation criterion, suggests that differentiation will undergo substantial reformulation in favour of the North. After Durban, China's and India's room for manoeuvre will further shrink.

Ms Natarajan still claims that the new instrument need not apply symmetrically to all countries, and even that binding commitments do not necessarily mean emissions reduction obligations.

But India's own BASIC partners disagree with this. More vitally, the Bali Action Plan has been dumped. The Working Group on Long-Term Cooperative Action established in Bali will be terminated in 2012, and a new process will begin, with considerable dilution of differentiation.

There is a case for introducing gradations and nuances into CBDR. The world has changed since 1992. China has become an industrial giant. Developing countries now account for 55 percent of global emissions.

But most developing countries are way behind the less affluent Northern nations in living standards, emissions, and capacity for climate action.

The big emerging economies should accept obligations less stringent than the North's. But it would be totally unjust to paper over aggregate North-South disparities. Yet, the Durban Platform comes close to doing this.

Click on NEXT for more...

After Durban, "might is right" will prevail, further vitiating the negotiations and wiping out past gains for narrow short-term self-interests of a handful of powerful states.

The process reached a low point at Copenhagen, where India too acted deplorably. It will now descend to more abysmal levels.

Susan George, an extremely perceptive observer, has called the climate talks "the most important negotiations ever undertaken in the history of humankind".

Over 20 years, these produced some gains and many hopes. But since 2007, they have gone downhill. The Northern leadership's will to fight climate change in the face of corporate opposition has weakened thanks to its slavish adherence to neoliberalism.

India could have better prepared itself for Durban had it practised coalition-building by offering AOSIS and LDCs need-based financial and technological assistance in climate change adaptation, and also strengthened the G-77 developing-country bloc. It could then have pressed the EU on Kyoto CP2, isolated obstructionists like the US and Canada, and produced worthy results.

India shouldn't have put all its eggs into the BASIC basket. The ad hoc grouping nearly disintegrated at Durban. But India didn't summon up the required policy independence and resilience. It lost the plot.