For people like me, all these fast-moving gadgets are not only costly and confusing but emotionally barren as well notes Barun Roy.

Photograph: Anonimski/Wikimedia Commons

In that classic movie, Roman Holiday, where Gregory Peck plays the role of a bored reporter for an American news agency, Audrey Hepburn plays the heir to the throne of an unspecified nation, who comes to Rome at the end of a long European tour.

She feels suffocated by the close watch of her guards and wants an escape to go on a night out to find out how common Italians live before her farewell march through Rome next day.

She gets her watchers drunk, gets drunk herself, and we see Peck recognising her lying on a park bench.

He brings her to his apartment to save her from the police. To him, it's also an unexpected news break. The story ramifies from there on. But that's not our point.

As Hepburn sleeps, we see Peck working on a desktop typewriter to write a story, page by page, adjusting its black-and-red ribbon from time to time, and waiting for a time slot to send in his report.

The thing is, nobody today, except clerks at courts and notaries, uses desktop typewriters any more. There is email and direct communication through mobile phones. The typewriter has simply vanished from our life forever.

As I wander the back lane of memory, I find so many other things have quietly faded away from our lives.

Like the 'Number Please' women. I think I was nine when I had my first exposure to a telephone. Beads of perspiration formed on the back of my neck as I lifted the handset and waited to hear 'Number Please'.

I gave the number I wanted to call, heard a clicking sound, and I was connected. That experience has gone forever with the inevitable wind of change.

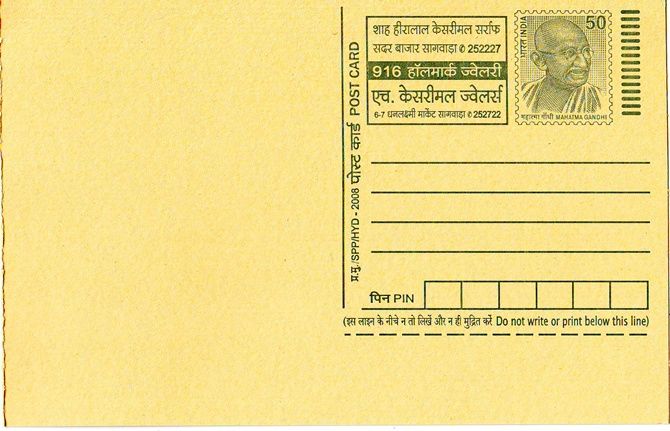

Other things have vanished as well. For example, the postcard and the blue-hued inland letter folder. I haven't received a postcard in my mail box in a decade or so.

Yet, at one time, it was a cheap and convenient way of keeping in touch with friends and relatives.

National artist Nandalal Bose used it all the time just to say "hello", sometimes putting in a quick drawing on the side.

I remember going to an exhibition of Benode Behari Mukherjee's postcard drawings not so long ago, where the exhibits occupied the walls of no fewer than three display rooms. Mukherjee was one of the pupils of Bose and considered a pioneer of Indian modern art.

I remember going to an exhibition of Benode Behari Mukherjee's postcard drawings not so long ago, where the exhibits occupied the walls of no fewer than three display rooms. Mukherjee was one of the pupils of Bose and considered a pioneer of Indian modern art.

Famous for his mural at Hindi Bhavan in Santiniketan, his postcards captured the lives of ordinary people, village scenes, farmers going to fields with their cows to till, city streets with horse-drawn carriages, clusters of banana trees by a pond, faces of tired old men and women, and whatever else appealed to his senses.

To this near-blind artist, when he could do no serious painting any more, postcards represented a wonderful outlet for a joyful celebration of life.

Gramophones have vanished too, those manually operated record players with turntables, using a stylus to play 78 round-per-minute discs. Even electrically operated players with more rpm capability are no longer available.

As a result, I am left with a huge stack of old records but no machine to play them. Of course, I could have them digitally transferred into CDs but that would cost me a bundle. That's a different thing.

Remember the Ray movie, Apur Sansar (The World of Apu), where Sharmila Tagore fans a coal-fired clay oven, filling the sky with billowing smoke? Well, we don't wake up to smoky mornings any more.

Electric and gas ovens have totally changed our kitchens and rid us forever of that daily choking experience.

Today it sounds like a fairy tale that mail used to be carried at one time in bundles on the back of runners, who ran faster and faster through the night to reach their destinations before the break of dawn.

Electric and gas ovens have totally changed our kitchens and rid us forever of that daily choking experience. Poet Sukanta Bhattacharyya, who died very young at 22, was inspired to write a poem about it. The lyric was later rendered into music. Hemanta Mukherjee sang those lilting notes: "The runner is shooting through the night, ringing those bells of his. The stars are twinkling in sympathy as the early dawn waits to send its message of compassion."

Electric and gas ovens have totally changed our kitchens and rid us forever of that daily choking experience. Poet Sukanta Bhattacharyya, who died very young at 22, was inspired to write a poem about it. The lyric was later rendered into music. Hemanta Mukherjee sang those lilting notes: "The runner is shooting through the night, ringing those bells of his. The stars are twinkling in sympathy as the early dawn waits to send its message of compassion."

Nobody sends telegrams any more. Those punching sounds "tick-tock-tick-a-tock-tock" are gone.

Mobile phones and short messaging services are there to do the job. Who writes with nib pens dipped in inkpots? Nobody. There are ball pens.

If you ask me if I miss them, my answer has to be: "Yes I do, but I can't help. Change has to take its own course. It is the great leveller."

But there are things I miss despite the march of time.

I miss the once-familiar early morning washing of roads, the rattle of first trams snaking out of their depots - despite the sad memory that poet Jibonananda Das, a habitual morning walker, was struck down and killed by one of them - and the chants of roaming Vaishnavites, who used to come round later to collect whatever one could give.

I miss the scent of flowers. It no longer hugs me like my beloved's arms when I go out on the street. I miss blue skies and starry nights, but air pollution has stolen them away. How I wish I could get them back in my life again!

Are we better off today than we were earlier? Perhaps. One has to walk the primrose way to the everlasting bonfire of change. But perhaps it's a change that's spinning far too fast for people like me, at 78.

Young boys and girls may not care, crazy to lap up new gadgets as and when they appear.

For people like me, all these fast-moving gadgets are not only costly and confusing but emotionally barren as well.