Dr Rajan’s export pessimism, and his dismissal of the value of an undervalued currency for a country trying to export, relies on a claim that India is substantially different from East Asian tigers that had 'weak firms and small domestic markets'.

Dr Rajan’s export pessimism, and his dismissal of the value of an undervalued currency for a country trying to export, relies on a claim that India is substantially different from East Asian tigers that had 'weak firms and small domestic markets'.

In two major speeches on Sunday, Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan made several thoughtful points about the global economy and the direction of monetary policy that deserve careful consideration.

At the Ramnath Goenka Memoral Lecture, Dr Rajan made a powerful case that India should no longer be seen as 'obstructionist' in global negotiations and instead build coalitions to 'influence the global agenda', thinking that is largely in line with the government’s own reconfiguration of such negotiations.

He also made the case for greater Indian representation at the high table; this links into his speech at the conference organised by the finance ministry and the International Monetary Fund where he repeated his warning, made several times previously, about the dangerous impacts on emerging markets of the “spillovers” from expansionary monetary policy in the developed world.

He called for the Fund to more clearly recognise the threat such spillovers posed to monetary policy, and for discussions to begin on whether a code could be formulated to promote stability under such circumstances.

From a realistic perspective, it is difficult to see how such a code could operate; it is to be presumed that Dr Rajan does not expect any such instrument to come into being in the near or medium term.

The RBI will be on its own in fighting the instability injected into the Indian system by developed-world central banks fighting recessions.

Dr Rajan also discussed, at considerable length, the question of the rupee’s 'true' value, and its impact on imports.

He argued that the impact of the exchange rate of the rupee on India’s exports was 'in the eye of the beholder', saying that the real effective exchange rate had been quite “flat” in the recent period even as India’s exports slumped.

His point, however, that the collapse in Indian exports 'is similar to what has happened elsewhere' is not quite on the money.

Even as India's exports have been contracting for several consecutive months, many countries in its peer group have in fact seen their exports increase while world trade has slowed down -- Bangladesh saw exports go up about nine per cent in the period between July 2015 and February 2016.

Vietnam posted a trade surplus in the first two months of 2016, with a three per cent increase in exports over the same period in the previous year.

Dr Rajan’s export pessimism, and his dismissal of the value of an undervalued currency for a country trying to export, relies on a claim that India is substantially different from East Asian tigers that had 'weak firms and small domestic markets'.

On the one hand, if Indian firms were indeed as competitive as the RBI Governor implies, they would not be clamouring for protection, and they would be doing better as exporters than they are.

On the other hand, it is dangerous to rely on policy based on the size of a domestic market; that argument leads to the temptation of protectionism.

The argument for a weaker rupee is, therefore, substantial.

While it is true, as Dr Rajan said, that capital inflows -- that push the rupee up -- are an important part of India’s infrastructure-building strategy, it is nevertheless the case that the RBI should not shut its eyes to the dangers of the rupee’s overvaluation being sustained.

Indeed, the government and its political leadership should resist the temptation of propping up the rupee in the mistaken belief that this alone would improve India's strength as an economy.

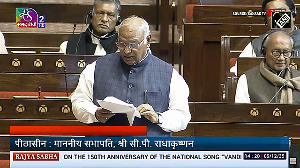

Image: An employee carries bundles of Indian currency notes inside a bank in Agartala. Photograph: Jayanta Dey/Reuters