In the past three months, the Bombay Stock Exchange benchmark, Sensex, has corrected 10 per cent from its highs and the valuations have fallen below historical averages.

In the past three months, the Bombay Stock Exchange benchmark, Sensex, has corrected 10 per cent from its highs and the valuations have fallen below historical averages.

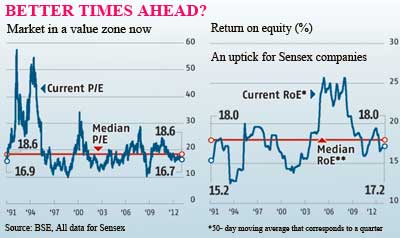

The index is now trading at a price-to-earnings multiple of 16.5 (trailing 12 months) on a standalone basis -- lower than its 20-year median earnings multiple of 18.6.

In the past, whenever its earnings multiple has fallen below the median, the Sensex has bounced back to give healthy returns to investors who put money in a falling market.

The index looks even cheaper if the expected earnings growth during the fourth quarter of 2012-13is taken into account.

In the first nine months of the financial year, the aggregate net profit of the Sensex 30 companies rose 9.5 per cent; analysts see a near-flat to marginal growth in the profit of these companies in the fourth quarter.

Many experts have been asking long-term investors to use the correction as an opportunity to enter the market.

“If FIIs continue to sell, markets may fall further from here but that will be an opportunity to accumulate quality stocks.

"You can never catch the bottom; it makes more sense to accumulate in a falling market than wait for the indices to hit the lows,” says Motilal Oswal Financial Services CMD Motilal Oswal.

Fund managers, meanwhile, have shifted their focus to large-cap stocks to ride out the storm. “I don’t expect any big fall from here and the Sensex will be range-bound till some clarity emerges on various macroeconomic issues.

This gives us an opportunity to accumulate select large-cap stocks,” says Swati Kulkarni, vice-president & fund manager (equity), UTI Mutual Fund. According to her, large-cap diversified funds have out-performed the benchmark indices in the past five years.

This should not be surprising, given the resilience shown by bigger companies during the economic downturn.

Collectively, Sensex companies offer 17.2 per cent return on equity, based on 2011-12 earnings -- the highest among all emerging-market indices and next only to the US Dow Jones, according to an analysis by Aditya Birla Money.

The ratio is likely to see a further uptick once the 2012-13 numbers are out. This might be the reason why the Indian market trades at a premium to its emerging-market peers, and foreign investors continue to buy Indian equities (see chart).

After the recent correction, the Sensex has lagged the recent growth in its underlying fundamentals, such as earnings, dividends and books value, on a trailing 12-month basis (calculated on a per-share basis, that is, per unit of index).

In

The divergence greatly reduces the downside risk from the current levels.

“On most valuation parameters, the Sensex is back to the level where it was during the lows of 2008.

"This greatly limits the downside risk from the current level,” says Devang Mehta, vice-president & head (equity sales), Anand Rathi Securities, though he adds that traders stop looking at valuation ratios when fear and panic grips them.

In the past 20 years, the index has moved in sync with the rise and fall in the underlying fundamentals -- it corrects whenever it overshoots and rises when its lags. The greater the gap, the sharper has been the ensuing countermove.

The Sensex began to run ahead of the fundamentals in 2006 and its price-to-earnings multiple crossed 28x by the end of 2007, while dividend yield fell to a 10-year low of 0.8 per cent. The index peaked on January 8, 2008.

The Sensex began to run ahead of the fundamentals in 2006 and its price-to-earnings multiple crossed 28x by the end of 2007, while dividend yield fell to a 10-year low of 0.8 per cent. The index peaked on January 8, 2008.However, by the end of 2008, the index had corrected nearly 60 per cent and was trading at a price-to-earnings multiple of 11x, and the dividend yield exceeded 2 per cent.

This led to a V-shaped recovery in 2009.

In the middle of 2010, it again began to overshoot the fundamentals, leading to a correction in 2011.

Thankfully, there is no sign of a similar exuberance right now. On all valuation parameters, the Sensex is reasonably priced and would get cheaper once the 2012-13 earnings and dividend payouts are taken into account.

The rate of India’s economic growth has been declining for two years now and is likely to bottom out, at around four per cent, during the quarter ended March 2013.

In 2003, the economic growth had bottomed at 3.8 per cent.

The bull run started within a few months of a decade-low economic growth and about a year ahead of the 2004 general elections. The scenario is not very different this time.

It will be keenly observed if the history repeats itself.