Cheap milk prices, rising fodder cost and the difficulties in buying new cattle and selling old ones on account of cow vigilantism have cast a triple shadow on this sunshine sector in Indian agriculture, reports Sanjeeb Mukherjee.

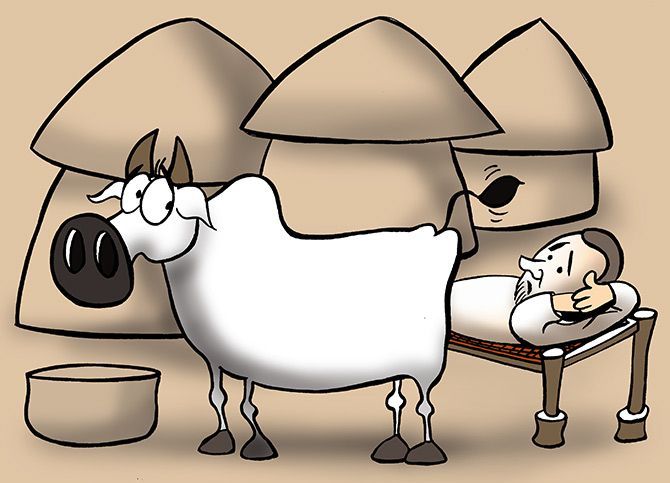

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

For 27-year-old Chaman Singh, the business of milk and dairying runs in his blood.

His forefathers have been milk suppliers and cattle farmers. Now, Singh is thinking of quitting this inherited business.

"I took a loan of around Rs 200,000 to modernise the business. Once that is repaid next year, I am seriously considering leaving the dairy business," he said.

The reasons for his planned exit capture the pressures in one of India's stellar agri-businesses today.

Cheap milk prices, rising fodder cost and the difficulties in buying new cattle and selling old ones on account of cow vigilantism have cast a triple shadow on this sunshine sector in Indian agriculture.

As with other agri-commodities, falling milk prices are the result of sustained over-production.

Between 2008-09 and 2017-18, India's milk production rose a staggering 57 per cent.

So much so, that even during the drought years of 2009, 2014 and 2015, milk production didn't fall, unlike all other farm commodities.

This steady increase in output has not only made the country the world's largest milk producer but also a big player in the global dairy and milk products markets.

But the jump in production has not been matched by adequate avenues to absorb the surplus. As a result, wholesale milk prices have plunged.

Traditionally, surpluses could be disposed of in the export market. But the plunge in global commodity markets has impacted skimmed milk powder (SMP) exports, too.

According to Global Dairy Trade, global SMP prices have more than halved, from $4,868 per tonne in December 2013 to around $1,965 per tonne in November 2018.

The impact of this sharp price fall can be seen in India's SMP exports. India usually exported around 100,000 tonnes of SMP annually. This has fallen to a trickle of less than 15,000 tonnes.

At the start of the flush season in July, India's big private dairies and thousands of cooperatives, which transformed a once milk-deficit country, had unsold milk stocks of over 150,000 tonnes.

No surprise then that the milk purchases, which started in October, were lower, driving down prices even further.

In north India, Singh says, buffalo milk is selling at Rs 32-33 a litre and cow milk for Rs 20-22 a litre, 30 per cent and 40 per cent below 2016 prices, respectively (surprisingly, retail prices have fallen only Rs 1-2 per litre in select cities).

"Earlier, a cow, which has an average yield of, say, 4 litres of milk a day, could fetch us almost Rs 200. Today, those earnings are not even Rs 150, while fodder costs have doubled.

"That is why the entire business has turned unprofitable," says former army man Satpal Malik, a farmer who runs a small dairy business with 16 cows and seven buffaloes on the outskirts of Delhi.

One solution to this problem of plenty in the dairy industry is to create new demand, especially via the myriad public food distribution schemes.

"If the government buys 200,000 tonnes of SMP from companies and cooperatives and distributes it through mid-day meal scheme in government schools or sends it to Africa as aid, much of the surplus problem could be solved," said Pushpendra Singh, leader of Kisan Shakti Sangh, a farmers' organisation.

Such alternative distribution channels could solve the economic problem associated with dairying but not the social stigma associated with transporting, purchase and sale of cattle that is turning out to be a bigger evil.

The cow vigilante movement, which has been gathering pace since the 2015 lynching of a man in his home on the outskirts of the capital, is taking its toll.

Recently, two incidents of cow vigilantes attacking a truck carrying cows and buffaloes were reported from Kathua. A police inspector was among two people killed in violence over cow slaughter in Bulandshahr.

The fear of being attacked by cow vigilantes has raised the risks of transporting cattle and pushed up bovine prices across the country, Uttar Pradesh in particular.

"In north India, because of the menace of gau rakshaks, the cost of a good quality buffalo, which gives an average of 10 litres of milk a day, has gone up to Rs 60,000-70,000 from Rs 35,000-40,000 in 2011.

"For good quality cows, prices have risen from around Rs 20,000 to nearly Rs 70,000-100,000," says Mohan Singh Ahluwalia, a member of the Central Animal Welfare Board.

Ahluwalia, a former president of "Gwala Gaddi", a grouping of small milk farmers, added that bovine purchase prices have risen even as selling prices of old bovine have dropped sharply because nobody wants to take the risk of owning cattle, narrowing the scope for fresh investments for the dairy farmer.

Earlier, old, infirm, non-milch cattle would have been sold at Rs 10,000-20,000 in the market. Nowadays, old cattle wouldn't even fetch Rs 1,000, Ahluwalia said.

"We used to sell old cows and buffaloes to butchers and get some money in return, which was invested for buying new, healthy cattle.

"These days, no one is willing to buy old cows or buffaloes, so we are forced to leave them in jungles because we can't afford to carry on feeding them," Singh added.

The number of gaushalas or cowsheds where old and infirm cattle can be sent once they stop giving milk are inadequate and those that do exist have poor facilities.

In Madhya Pradesh, for instance, cows from a local gaushala are released into farmers' fields at night, destroying their crops.

The long-term prognosis, therefore, looks grim.

"If you keep adding factors that are cost-imposing, India's milk producers won't remain competitive in the global markets and if there isn't any growth in demand, your natural growth in milk production will suffer," said T Nandakumar, a former agriculture secretary and ex-chairman of National Dairy Development Board (NDDB).

In such a situation, he added, the bovine population may not fall but farmers will underfeed the animals, causing them to produce less milk, which will impact overall output.

Given that most cattle farming is done in India by small, landless farmers, the situation could get acute for them unless the Centre and state governments move quickly to shore up the business -- both in terms of its basic economics and the societal issues that are acting as an additional disincentive.

On current reckoning, India's most successful agriculture story in the last decade after BT Cotton is in danger of losing the plot.