'China has reclaimed, after two years, its mantle as the world's fastest-growing large economy.'

'This, when its working age population is shrinking, while ours is growing.'

'And talking of jobs, China expects to create 11 million urban jobs this year; for India, don't ask,' says T N Ninan.

In India, the housing market is in the doldrums.

In China, house prices in the last two years have risen by more than 40 per cent, and mortgages now account for half of all new bank loans -- double the share a year earlier.

In India, the government is looking for ways to boost economic activity; in China, they are shutting down aluminium plants to control pollution, and clamping down on the housing market.

In India, the debate on special economic zones saw a brief revival before dying down; in China, the Xiongan New Area, south of Beijing, is being launched as another Shenzhen in the making (2,000 square km, a third bigger than Delhi state).

In case you missed the point, Shenzhen's GDP is equal to more than three-quarters of India's.

While we talk of Make in India and of exploiting low wage costs, Xiongan is designed for high-value-added industry.

In China they have built ghost towns; in India we have half-built tower blocks.

The ghost towns deliver revenue, because in China money from the sale of land use rights goes to local governments and accounts for 30 per cent of their income.

In India the costs are borne by might-have-been home-owners. The benefits often go to clever operators; ask Mr Vadra.

In India, we have imposed anti-dumping duties on steel imports, and bankrupt steel companies are to be auctioned by banks; in China they added new steel-making capacity in 2016 that is equal to half of India's annual production.

But in some areas, the two economies are on the same page: Both have seen exports fall 10 per cent over two years, and both have seen trade revival in 2017.

The difference is that China has a trade surplus while India has a growing deficit.

Despite that, and higher inflation to boot, the rupee has dropped less than the yuan, against the dollar, over the past three years.

Then there are the mysteries of debt.

In India the ratio of corporate debt to GDP is only 51 per cent; in China it is a whopping 169 per cent.

Never mind the difference, in both countries the private corporate sector has slowed fresh investment.

With government debt it works the other way. China's debt to GDP is only 46 per cent, compared to the Indian government's 69 per cent.

So Beijing has the fiscal headroom to push for growth, and used it last year; the Reserve Bank has ruled that out for India.

Finally, Indian households have a 10 per cent ratio of debt to GDP; the ratio for Chinese households is 45 per cent.

Yet it is Chinese households, not India's, that are fuelling a housing boom.

In terms of systemic risk, China's overall debt is more than 250 per cent of GDP, while more conservative India's is barely half that.

Yet China's ratio of fresh investment to GDP is 50 per cent higher than for India.

Therefore, every forecaster has declared China's growth is unsustainable. Beijing said so too, and planned to step on the brakes for 2017, to bring down growth by two notches to 6.5 per cent.

Only to step on the accelerator; growth was 6.9 per cent in the first half.

Here we keep saying things will improve, but they have tended to go the other way.

So China has reclaimed, after a gap of two years, its mantle as the world's fastest-growing large economy.

This, when its working age population is shrinking, while ours is growing.

And talking of jobs, China expects to create 11 million urban jobs this year; for India, don't ask.

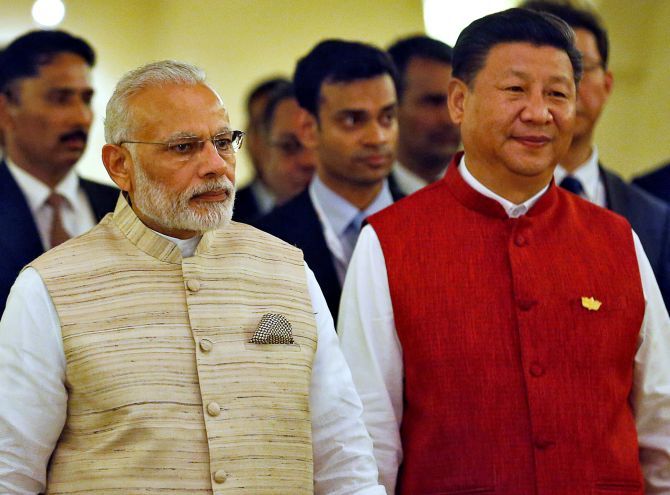

IMAGE: Prime Minister Narendra D Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping at the 8th BRICS summit in Goa, October 2016. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters.