India's likely medium-term potential growth will almost certainly be markedly lower than that experienced in pre-pandemic years, predicts Shankar Acharya, former chief economic adviser to the Government of India.

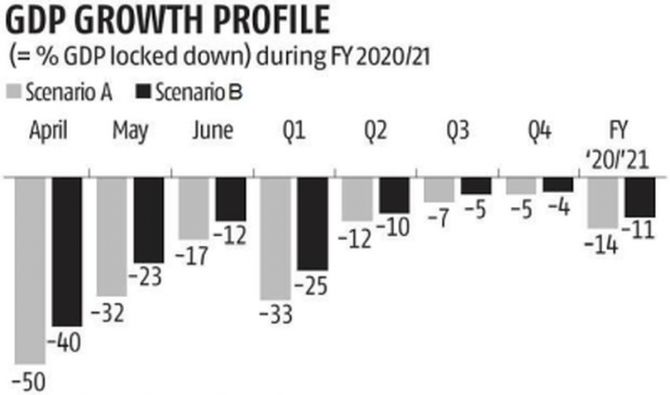

Almost exactly a year ago, hardly three months into the Covid pandemic in India and seven weeks after the imposition of a national lockdown, I had projected that GDP in the first quarter (Q1) of 2020-2021 would crash by 25 per cent (y-o-y) and full year GDP could plunge by 11-14 per cent.

At that time, the government, international organisations like the IMF/World Bank, leading investment banks and credit rating agencies were still expecting positive growth in 2020-2021! In the event, 2020-2021 Q1 GDP did crash by 24 per cent.

However, thanks to a remarkably swift recovery in Q2 and Q3, following the lifting of the lockdown, the full year GDP drop was contained to 8 per cent, still a record decline for post-Independence India.

Today, more than two months into the devastatingly ferocious 'Second Wave' of the pandemic and six weeks into the new financial year, what can we speculate about the economic outlook?

At present, the earlier referred cast of institutional projectors still expect current year GDP growth of around 9-12 per cent (essentially driven by recovery from the previous year's low base).

But now, two months later, that expectation looks decidedly optimistic.

March and April have been deadly months as officially tallied, daily infections and deaths have soared to levels of more than 400,000 and 4,000, respectively, (both numbers considered serious underestimates by many experts) the national health infrastructure has crumbled under impossible stresses, and a sluggish, supply-constrained vaccination programme has not done much to mitigate the ongoing health disaster.

Inevitably, regional lockdowns and curfews have proliferated, especially in some of the most economically productive states like Delhi, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

After the disastrous economic impact of the spring 2020 national lockdown, the central government has, so far, wisely resisted imposition of another national lockdown, despite substantial pressures for such a measure from both medical and political quarters.

The economic impact of the surging pandemic and regional lockdowns is already visible in the high frequency economic indicators for April.

Fresh vehicle registrations have fallen to a nine-month low.

Google data on visits to retail and workplace show sharp declines.

Power generation and fuel demand have dropped.

The overall employment rate (total employment divided by working age population) is at its lowest level since June 2020, with over seven million people losing jobs during April according to CMIE data.

The number of households availing of the national rural employment guarantee programme in April was about 80 per cent higher than a year ago.

Economic distress among the poorer half of the population is clearly on the upswing, and this after the huge shock suffered by them in spring-summer of 2020.

With the second wave of the pandemic raging pretty much out of control, and the prevailing pattern of rolling, temporary, regional lockdowns likely to continue, it is extremely difficult to predict the trajectory of economic activity over 2021-2022.

That trajectory will be determined by the interaction between the evolving pattern of supply restrictions, the health and commercial risks perceived by economic agents and the emerging profile of major demand aggregates, that is, consumption, investment, net government expenditure and net exports. The outlook for all of these is uncertain and subdued.

Nevertheless, at the risk of being foolhardy, here are a couple of guesstimates for now.

Real GDP in Q1 of the present year is likely to grow by around 15-20 per cent (y-o-y) from the deeply depressed trough of 2020-21 Q1.

This compares with earlier expectations of 25-30 per cent growth.

Basically, I foresee a significant dip from the GDP levels achieved in Q3 and Q4 of last year, perhaps in the order of 5-10 per cent.

So, when the National Statistical Office releases their Q1 estimates at end-August, the high growth will find many cheerleaders in government and outside.

But it will represent an appreciable drop in the level of economic activity from that enjoyed in the last quarter of 2020-2021.

Importantly, GDP in 2021-2022 Q1 is likely to be significantly below the level in 2019-20 Q1.

For the full year, 2021-2022, projections are even more dicey, given the prevailing massive uncertainties about the course of the pandemic, the vaccination programme, the possible proliferation of dangerous new virus variants, the governmental policy responses at all levels and global economic and political events.

Still, following on the path of foolhardiness, I would be surprised if economic growth in 2021-2022 is much outside the range of 6-8 per cent.

While one can readily anticipate the proud headlines of 'fastest growing large economy', let us not lose sight of the harsh reality represented by such numbers.

They would mean that the level of real GDP in 2021-2022 was still below that enjoyed in 2019-2020 (a 9 per cent growth would bring GDP up to that level).

What's more, compared to the likely pre-pandemic trajectory of output and growth, India would have lost at least 10-12 per cent of GDP increment forever.

Furthermore, since the pandemic and lockdowns will inflict deep scars on the society and the economy, India's likely medium-term potential growth will almost certainly be markedly lower than that experienced in pre-pandemic years.

What about policy to promote a better outcome than the one outlined above? By far and away the best policy is a greatly ramped up programme of vaccination against Covid.

It is a tragedy that vaccine production, distribution and injection has not proceeded at a much faster rate.

That would have helped mitigate the severity of the second wave and its unfortunate health, mortality and economic impacts.

To the extent the programme can be substantially accelerated, its beneficial effects on health, lives, livelihoods and overall economic activity could be quite large.

After the massive expansions of fiscal deficits and monetary liquidity in the past year, the scope for further increases is extremely small, without seriously risking financial stability, debt sustainability and damaging levels of inflation.

Shankar Acharya is honorary professor at ICRIER and former chief economic adviser to the Government of India. Views are personal.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com