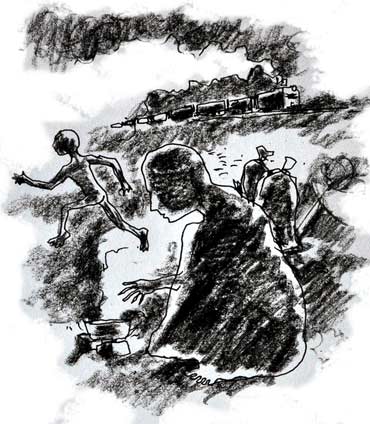

Bharath Moro journeys by train through the grim coal terrain of Jharkhand and meets an unlikely band of women.

It's 6 am and there is a fierce wind blowing across Dhanbad Station. I am tired, my feet hurt and my nose is simultaneously being assaulted by the damp, fetid smell of a city that's taking a collective morning dump and the pungency of chillies and eggs being broken into a pan smoking with mustard oil. I also get the feeling that I am lost. This despite the fact that my fellow traveller is VSP.

Both of us are in Dhanbad after a whirlwind tour of Varanasi that was overwhelming. Too many sights and smells crammed into a six-hour window followed by what I tell myself later was a foolishly indulgent piece of theatre. All to prove to myself that I could travel general class, in the harshest of winter, on one of the most crowded trains in the country -- the Howrah-bound Kalka Mail.

VSP is back after purchasing tickets, which we will use to board the Dhanbad-Ranchi Passenger. Confident as ever, he points in the direction of Platform 5 and says "Let's go, that's where our train will arrive." While we wait for it, I pick up a copy of the Dainik Jagran -- the only newspaper available.

My Hindi is rustic at best and I struggle to read a story about a mine fire that's eating up roads near Hazaribagh. VSP, meanwhile, seems more interested in eating scrumptious-looking omelettes, which are promptly ordered and devoured.

There's a bit of a scramble when the empty rake eventually arrives, but we eventually find side window seats in an odd coach -- there are no toilets at either end! Only later on do I realise that it is a retrofit of a MEMU (mainline electrical multiple unit) coach.

There's a gentle bump as the locomotive is attached. I venture out to note that it is a venerable WAM-4 from Mughalsarai. The paint is peeling off in chunks, taking bits of the shell with it! It clearly has seen better days and I head back wondering how long it will remain in active service.

Back in the coach, VSP is busy pouring over his timetables and making notes for our journey later on in the day. The plan is to head back to Tatanagar from Ranchi using the MEMU via Muri and Chandil.

There is a certain comfort in having a person like VSP around, knowing that at your disposal is probably the best brain holding vast amounts of train data. For an intrepid traveller like me, who dislikes too much planning and too much structure to his journeys, it can get overwhelming -- but not today!

Ten minutes later, with a gentle toot from the WAM-4, we get moving. Six metres into the journey and I immediately realise the folly of choosing a window seat in the direction of travel on a cold, cold December morning.

There's an irritating one-inch gap that the glass shutter will not cover and the thin blast of frigidity is relentless. But I look past this minor irritant as we negotiate our way through a maze of lines and catenaries.

Rolling through the crowded suburbs of the city, I notice how everything seems to be covered by a thin sheet of coal dust -- the rails, the catenary poles, the sleepers, the houses, the drains. Even people seem a shade darker than usual.

Our first stop is Kusunda, a station with raised earth platform, a ramshackle room that dispenses tickets and a few dogs scratching themselves awake. I don't notice it immediately, but on the other side of the station and towards the south is an enormous yard, six to seven lines all occupied by rakes overflowing with coal.

Through the dirty glass of the shutter, I strain to make out the details. Suddenly, I let out a low yelp. No, not a weird locomotive sighting, but a man is on top of one of the wagons and busily throwing down huge lumps of coal, which his helper down below is stuffing into a sack.

He is six inches away from certain death and yet there is a calmness and assuredness behind this pilferage that is amazing. I point this out to VSP and in his characteristic Deccan-y twang, he says something that can't be repeated here.

We trundle along through the fog and cold at a leisurely 45 kmph. The tracks are in pitiable condition and the bounce and gait becomes disconcerting after a while. A line appears suddenly from a corner and disappears just as suddenly. This happens quite often and after 5 minutes, I give up trying to find out the origins of these spurs.

The halt at Baseria comes and goes without much fuss as we pass by enormous dumper trucks carrying coal, waiting patiently at a couple of level crossings. Somehow, the black seems all-pervasive. I have no clue just how much darker this is going to get.

Illustrations: Dominic Xavier

Rail enthusiast Bharath writes a blog titled http://www.purisubzi.in.

'Every single person who loaded the sacks is a woman'

A proper station at last comes into view. Sijua has a high-level platform and a footbridge. And lots of people milling around on the platform, waiting to board. Unusually, none seem the office-going type. Everyone has a sack or two of coal in front of them and wait patiently, almost cat-like, to pounce on the train and get in.

Thud, thud, thud! The entire coach shudders as a dozen coal sacks land heavily near the doors. There's shouting, screaming and rabid gesticulating as more people, mysteriously appearing out of nowhere, get in on the act. More floor-pounding, more coal sacks landing. The loco hoots once, which results in the noise level reaching ear-splitting levels.

Quick, sharp words are exchanged between people who've loaded the sacks and their 'controllers' on the ground. One more hoot. This time the chain's pulled and there's the loud hiss of air escaping the valves. I am trying to make sense of what is happening, but it seems surreal, as if Andre Masson himself decided to paint the scene unfolding before me. Big blur of people, voices and coal dust. But in this chaos, I notice something that makes me go, "No, it can't be. Are you really sure?"

Every single person who loaded the sacks and remains with them in the coach is a woman.

We get going eventually, after more hollering. The women clearly seem dissatisfied with their progress in getting the sacks on board and in what seems to be a fight between two rival groups, fingers are pointed and words are exchanged. Doors, ahead and behind me are jammed with these sacks. The women climb over a couple of them and fan out through the coach identifying places to store them properly. Loud arguments break out between people occupying seats and the coal women trying to shove them underneath.

In the adjacent bay, one man almost chokes a well-built and hefty woman, but calm prevails after a few others intervene. The burly woman very nonchalantly shows him her middle finger and gets on with the work at hand!

Angarpathra comes and goes with very much the same action at Sijua. There are now coal sacks stacked right up to the roof of the coach. Every inch of available storage seems to be taken -- except the space beneath my feet. I have resolutely put my foot down and not allowed any coal underneath me. I feel rather smug and proud. And with a guffaw, VSP seems to agree.

That's when I notice her.

Her eyes seem to be seeking something as she peeks from behind the partition of the first bay. A shimmer. And just like that the space beneath my feet is taken. I seem arrested by her presence and offer no resistance when she asks me to move. The sack comes thudding down from the strap on her head and after a few struggling seconds to contain a small tear, everything quietens.

"Thank you," she says in a very weak voice.

"It's okay," I mutter back.

And for the second time, I am astonished. There is a small baby tied to her bosom using a rudimentary sling. However did she manage to lift the sack and her baby and get into the crowded train? What is her name? Why does she do this coal-pilfering? Isn't she afraid of getting caught? Why am I seeing only women carrying these sacks? Questions like these flash through my head. I want to ask them and receive answers. Somehow, her appearance has completely managed to turn this leg of the journey into something different. Something that I am unable to point at and pick out.

Meanwhile, VSP momentarily distracts me to announce that we have arrived at Katrasgarh Junction. It is a smallish one, flanked on both sides by the now very ubiquitous coal-loading yards. And no surprise, most of the lines are occupied with overloaded rakes.

We start after a two-minute halt and continue to trundle through the vast, almost featureless, black terrain. A small rivulet called Tentulia flows swiftly by as we cross the eponymous station.

As VSP buries himself in his timetables, I take up the courage ask the child-slinging woman a few questions. My curiosity cannot be contained any longer.

"Do you mind if I ask you a few questions?"

"No saab, but I don't know why you want to talk to a person like me."

'Wait, what? You eat mud for dinner?'

Her eyes are sharp and clear as she begins to answer. Her frail and thin frame hides a very confident voice that has a very sexy rasp. Rupa.

"So, Rupa, why do you carry these coal sacks? Where do you get them? Where do you take them? And why is that I only see women doing this work?"

"Saab, what to do? We are poor and we have no other work. The big mines around this place are either closed or don't employ people like us, so we all pool together and dig these small holes that are not officially allowed. We then take the coal out from them and sell them at the market near Bokaro and Kotshila."

I am about to ask her another set of questions, but she's talking rapidly and completely into the flow.

"Sometimes the babus come and close the holes, so we have to steal from the trains and sell the coal, like today. Yesterday, three men came up to my village and thrashed a few of us and asked us not dig these holes. See this big bruise on my left hand," she is pointing towards a red welt, "This was caused by one fellow trying to drag me away, but luckily my neighbour saw it and chased them away with a stick."

The baby shifts in her sling and seems to be waking up, but she caresses it back to sleep. "His name is Arjun." There is an extra twinkle in her eye as she goes on for a few minutes about how she's the only person among these women to take care of her baby and work at the same time.

"But isn't this kind of work dangerous?"

"Yes it is, saab. But I have to do what I have to do to give my baby a good life, no?"

"But don't you have a husband who can help you with it?"

There is a twinge of regret as soon as the words are out of my mouth and I can't help notice that she doesn't want to answer. She doesn't. Several minutes of uncomfortable silence pass, in which I try to distract myself with more of the black bleakness outside.

Phulwaritanr comes and goes with the line from Mohuda to Gomoh flying overhead, a little outside the station. We halt for a couple of minutes on either side of a bridge spanning the wide and very dirty Jamunia river.

At both halts there are lines that come together and then split and as VSP goes gamely on with the details, I try to take in as many of them as possible. Dugda is a biggish halt with a sizeable crowd disembarking and boarding. There is a flurry of activity in the coach as a few of the women unload and take on sacks. Rupa, meanwhile, is stone-faced and has buried her head in her hands, refusing to look up.

The line meanders through a series of deep cuttings and emerges into a clearing that is bordered by a very thick jungle. This is probably the most dramatic turn of scenery I have witnessed in a long, long time. A few metres down, a pair of lines join us, which VSP happily informs me are the main tracks from Gomoh to Chandrapura. The sight of these stirs the coach into a frenzy. The hollering begins; sacks are bought down from the luggage racks, shifted from below and crammed into a giant pile near the doors. I get the impression that the train will soon come under really heavy artillery fire and the bags are meant as some sort of protection!

We slowly pull into the station, at what looks like Platform 1. There are about half a dozen lines separating us from a platform on the other side. And as usual, all these lines are occupied by faceless, nameless WAG-7 hauled coal rakes. VSP takes this opportunity to stretch his legs a bit, but I stay put, wanting to talk to Rupa some more. She senses it.

"What to say about my husband, saab? I married him because my mother needed the money and he paid Rs 1,500 on the spot. I don't like him. Tell me, which 20-year-old girl will want to marry an already twice-married man who has a big drinking and gambling problem? Will you give your sister to such a person? Will your mother agree, even if you say yes?" The vehemence and hurt in her voice are clear.

"He doesn't work at all and he beats me if I don't give him money at the end of the day. I earn 35 rupees a day, by carrying these two sacks for more than 100 kms. What money do I have left for me and my baby, huh?"

I am shocked at this obscenely low amount, but before I say anything, she rattles on.

"For each sack we make 70 rupees, but we have to pay all these people. The railway police," she hawks and spits as she mentions them, "the people who help us dig our holes, the station master and coolies and the others". I don't have to guess who these 'others' are.

"On some days, all my money is taken from me. I start the day with nothing and end up with nothing. I dig up some fresh mud outside my house and eat that for dinner because I can't afford anything else."

"Wait, what? You eat mud for dinner? Please tell me you are only joking."

"Do I look like I am joking, saab?"

Wow. Space and time compress. Everything seems a blur. The loud wail of a passing WAG-9 only adds to the whirlpool of surrealism in my head. Sharp and piercing. Blocky and bulky. Colours that I can't even imagine start appearing and form a film before my eyes. Thirty-five rupees a day? Eating mud for dinner?

'Rupa's words continue to haunt me...'

I am shaken from my trance by VSP, who's returned from his walk. He curses the unusually long halt we've had. I nod, pretending to agree, but in reality my concept of time seems to have been shot.

Rupa's gone too, helping another woman load a sack of what look like vegetables. It's covered in black dust, so I can't tell at the moment.

The cause of our interminable delay soon turns up -- a grossly underpowered single WAG-5 hauling a fully-loaded rake. Within a few seconds, we are given the go-ahead and with considerable effort, we are finally off. The thick vegetation continues as we loop around the giant thermal power plant and cross the Damodar River using a classic truss bridge.

Next stop Bokaro. Home of the giant steel plant, many, many more industries and for us rail fans, the most zany liveried WDM-2 locomotives.

The station is clean and modern, befitting a town that seems very confident of its place in the world. As we pick up speed after a five-minute halt, I notice that the streets are clean, well-maintained and sterile. Seems like the perfect township, but with the character of an operating room.

The landscape changes dramatically again. After the black of Dhanbad and lushness around Chandrapura, this seems very desert-y. Small rolling hills of decaying shrub, littered with broken and decaying houses. Only the colours seem to have changed. The bleakness remains. The villages of Radhagaon and Pundag come and go quickly and the crowd in the coach starts to thin. Rupa is suddenly nervous as we approach Damurughutgu Halt. Her weight shifts constantly and she keeps knotting her fingers.

"What happened? Why are you so nervous?"

She looks around to make sure no one else is paying much attention.

"The hafta fellow usually comes on here and takes the money. But today I have nothing, so I don't know what to do. I hope he doesn't come." She sounds hopeful.

Her wish doesn't come true though, as a very thuggish-looking and muscular chap boards and starts eyeing the remaining women with coal sacks.

I can see small notes being passed around quietly and nervously. It is Rupa's turn. I want to intervene and do something, but I don't and with an almost invisible bat of her eyelid, Rupa indicates that she's glad of my decision. There's a loud argument between her and the goon, which results in her baby waking up and bawling.

Threatening gestures fly from both sides as I desperately try to keep calm. One of the other women intervenes and in about half a minute everything seems to have been worked out. Rupa is in tears, though. I ask her what's been promised to the goon, but she refuses to divulge. Everyone just goes quiet.

I am distraught and want to help, but I am afraid to do so. Despite her struggle, Rupa is a proud woman and won't take kindly to any pity. But I overcome this feeling and withdraw a Rs 500 note from my wallet and extend it to her. She balks.

"Saab, I don't need this. Why are you giving me this much money?"

"Please take it. It would mean a lot to me if you took it and used it for something you and your baby need."

"Saab" She hesitates. For a long time. But eventually she takes it and puts it into her baby's sling.

"Thank you, saab. I don't know what to say."

Before I can reply, there are loud noises from across the coach and about six women converge towards the door. I notice that we are slowing down. Rupa gets up and joins the rest of them as we pull up to halt at Kotshila. There's near-panic as about 25-30 sacks are rolled off on either side of the train. Rupa gets down too.

"This is where I sell the coal in the market. It's across the station there," she says, pointing towards the far end.

"Thank you again, saab. You are a complete stranger to me and I really don't know why I talked to you. I am sorry if I told you something I shouldn't have."

"No, no, don't be sorry."

And with that she's off. Lifting her sack and her baby and walking towards a Rs 35 reward for her labour.

We halt for quite awhile to allow the Hatia-bound Shatabdi to overtake us. VSP is all excited and awaits the run through with a great, beaming smile. But my mind is elsewhere. The overtake done, we swiftly progress to Muri Junction, where a giant aluminium plant that belongs to the Birla Group looms over the town and station. I venture out to buy something to eat, but return empty-handed.

The scenery out towards the climb from Muri to Ranchi is spectacular, but I can't get my head around to enjoy it. Rupa's words -- "Saab, what to do? We scavenge coal and eat mud. This is how our life is" -- continue to haunt me.

Comment

article