As Lok Sabha speaker Meira Kumar's daughter, politics as a career was perhaps an obvious choice. Yet somewhere between getting a degree in business and working in marketing, Devangana Kumar discovered her love for history and art. The result is an opulent and colourful collection called Pageants of the Raj.

It started with a postcard, an old picture really. The picture was that of a colonial peon who stood obediently beside a chaise longue dressed in a sherwani with a matching hip sash. The postcard was labelled 'Office Peon'.

This rather quaint picture postcard piqued Devangana Kumar's interest. It wasn't the first postcard of the kind she had owned -- Kumar had been collecting colonial postcards and pictures such as these for over seven years before she decided they could be of more worth than just lying around at her home as part of a collection that few saw and perhaps fewer appreciated.

So about three years ago, Kumar decided to put these postcards to better use.

"I have been collecting (colonial) images and postcards for over ten years now -- from flea markets and antique shops to the Internet -- and about three years ago I decided to do some research about these images, about why postcards featured these photos (of domestic helps) specifically," she says.

A lot came out of the research most of which was conducted in New Delhi's Nehru memorial library. Kumar learnt more about their roles, what they did and how they were identified.

"The British would send these postcards around the world, to showcase to the outside world what India was and (perhaps unconsciously) underline the (white man's) burden that lay on their shoulders to civilise the people they ruled over," she says,

Hence you had the nameless army of domestic helps that was photographed (sometimes against their will), labelled, identified not by their names but rather by their profession and sent around the world to be consumed by people in far away lands.

As an identity reclaiming of sorts, Kumar began first by christening the people in the postcards.

"None of them had real identity. What they did in (the house of the sahibs) was denoted by their uniform. So I started out by giving them names -- fictitious names but names nonetheless."

So the barber was named Ismail, the khidmatgar became Abbas Khan, the aabdar got Gaj Singh as his name and so on.

Following an elaborate process, the postcards were enlarged to life-size images.

Devangana Kumar's version of the sepia-toned postcards is colourful and the characters that inhabit them wear coloured clothes. All the images are Giclee prints on velvet or silk; some of these have fine embroidery embellished with beads and add-ons that range from brass to Swarovski crystals.

"You do not tend to associate silk and velvet and bright colours with the working class of the time. The idea was to give them bright coloured clothes and fineries that would have been denied to them because they were considered impure," she says.

Thus some of these working class heroes and heroines do not necessarily 'look their part'; the office peon for instance, looks like an important person after the embellishments (the only thing giving away his identity being his bare feet) or one of the khidmatgars seems ready for a royal procession.

It is evident that much thought has gone into these images so it comes as a surprise when Kumar tells me she never studied art. "Or history for that matter," she adds, "I studied business management in Australia, returned to India and worked in marketing before getting married and having a baby!"

Yet, Devangana Kumar was never too far from art. Her mother, the Lok Sabha speaker Meira Kumar was a painter before her career in politics took over. "My brother is an antiques collector and my sister-in-law is into craft," Kumar says pointing out that her family's sensitivity towards art and history as well as empathy for the downtrodden perhaps influenced her in ways she never imagined.

Kumar's husband, Amit Tyagi runs a chain of kebab takeaway counter in Delhi while Kumar and her sister Swati run Tota Maina Designs a company that creates handcrafted lifestyle products. Kumar also independently runs Itum Bomb a company that turns around mundane objects into edgy collectibles.

Over the last three years though, much of her business has taken a backseat as she dedicated herself largely to putting together this exhibition that has had a run in Delhi and is showing in Mumbai's Tao Art Gallery till November 15.

Kumar eventually plans to put together a sequel to the show, featuring the downtrodden and forgotten before she seeks out photographs of the maharajahs for inspiration. In any case, she says the focus will be on the human factor rather than the opulence that we so often associate with the Raj or the royalty.

As we stand looking at one of the images on display -- the interview's been over for a while -- neither speaks. She breaks the silence telling me about art that moves her and inspires her own work.

"Art must make you think. It should make people look beyond the obvious and make them think. People have stopped thinking; they've stopped asking questions." she says without turning around.

I ask if she supposes her collection will do the same.

"Perhaps," she says still looking at the image, "Perhaps it will."

In the pages to follow, we bring you images from the exhibition itself, alongside excerpts from Devangana Kumar's essay A Pageant of Colonial Stereotypes: A 'Native' Workforce to give you an insight into the world that was.

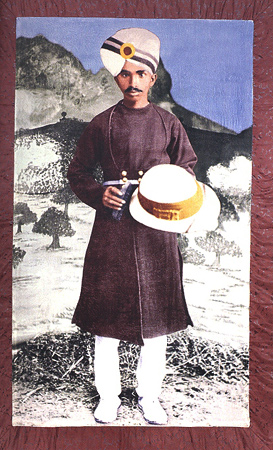

The office peon or chaprasi

As defined by George Clifford Whitworth, the office peon or chaprasi was a servant or messenger who wore a chapras or brass plate on his shoulder belt, as a badge of his office. On the chapras was engraved the name of the office or the name of the master who the messenger served. The chaprasi was the primary mode of communication between the colonists; he delivered on foot the notes or chits exchanged by the sahibs and remained in attendance at the veranda. He was also the main source of conveying gossip between the memsahibs. In the office, he circulated files and served tea.

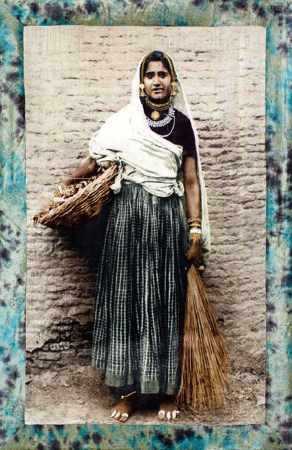

The Mehtrani

They were also known as bhangis. They swept the compound and the inner spaces of the colonial house. They were at the bottom of the social structure of the colonial household, the least paid, and the poorest. Nevertheless, they performed a crucial role in the functioning of the gussal khana or bathroom, their most important duty being to service the 'commodes' or 'thunder boxes' of the sahib and his family. They conscientiously performed their karmic duties in the hope of ridding themselves of the burdens of this life in their next birth.

The hajaam

He was a part-time servant of the colonial household. His duties involved hairdressing, shaving, cutting and trimming nails, and cleaning the sahib's ears. The memsahib, too, often employed his hairdressing services.

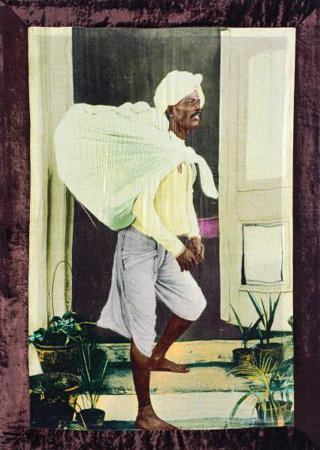

The dhobi

He was usually a part-time domestic servant who transformed dirty laundry into clean, bleached, starched, ironed, and neatly folded clothes. His services were indispensable to the colonial household, which accumulated huge piles of soiled linen and dirty curtains. The heat and dust of India compelled the colonial family, usually overdressed in an attempt to ward off the hot Indian sun, to bathe a few times a day to cool off.

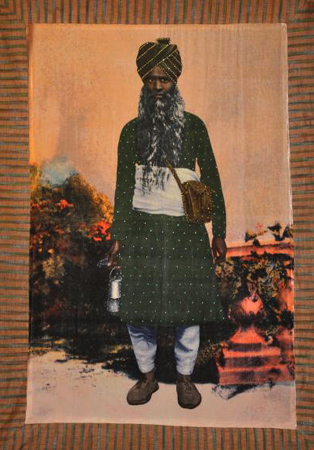

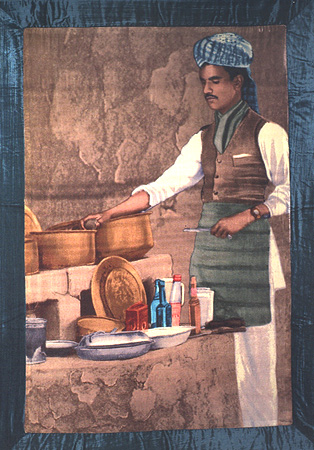

The khidmatgar or khidmatgor

Col Yule in Hobson–Jobson writes that the khidmatgor 'is the Anglo-Indian word applied for a musulman servant, whose duties are connected with serving meals and waiting at the table'. It was standard for each member of the family to have two, or sometimes even three, khidmatgors at their service. The khidmatgor accompanied the sahib to public and private gatherings. Positioning himself behind the sahib's chair, he attended to the needs of his master, moving silently to light a pipe, to offer a cigar, and occasionally wiping beads of perspiration from the brow of his employer.

The butler

According to Col. Yule in Hobson–Jobson, 'This is the title usually applied to the head servant of any English or quasi English household. He generally makes the daily market, has charge of domestic stores, and superintends the table. As his profession is one, which affords large scope of feathering a nest at the expense of a foreign master, it is followed by men of comparatively good caste.' The butler together with the cook was at the top of the domestic hierarchy of the colonial household, and was the highest paid. He was concerned with the running of the entire household, from keeping accounts to superintending other servants to making purchases from the bazaar. In contemporary India, the butlers role has been taken over by that of 'house manager'.

The bawarchi

He was also endearingly called bobajee. He was also the highest paid member of the retinue of servants. He was usually confined to the bobajee khana or kitchen, which was attached to the servants' quarters. In the absence of stoves, he cooked on a simple mud-brick chulha, with primitive cooking pots and utensils, yet he was capable of preparing a well-dressed three-course dinner for any number of guests.

Abdar or the walking refrigerator

Defined by George Clifford Whitworth, the abdar was 'a servant whose office it is to prepare water for domestic use'. It was the duty of the abdar to cool the water, wine, beer, and other table delicacies, and to serve these to the master and his family and guests. He was like a walking refrigerator and accompanied his master to dinner parties, carrying cold water and other cool refreshing drinks.

The knife grinder

He frequented the colonial house along with his stone-grinding wheel to sharpen knives, cutlery, and other metal tools. He played an important role in the smooth running of the kitchen, honing knives that had become blunted from cutting through tough meat.