The day the Class X exam results were announced, Dhanalakshmi rushed back home from work in the afternoon.

She had found out by checking online that her daughter, 16-year-old Sridevi, had failed the exam and she was worried she might not be able to handle the disappointment.

But when she reached their two-room house in the crowded quarter of Jogupalaya in Bangalore, it was to discover the body of her son, 19-year-old Shekhar, hanging from the ceiling.

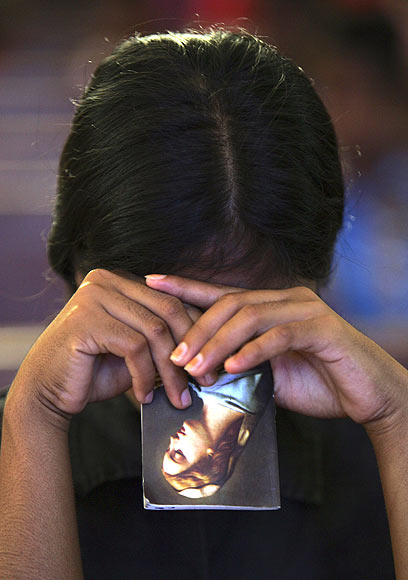

A week after the incident, Dhanalakshmi cannot bring herself to talk about it -- her sobs prevent her.

Her sister, O Jayalakshmi, and daughter try to explain, perhaps to themselves as well, why Shekhar took this drastic step while she gazes at the photograph of her son, and the small lamp burning in front of it.

Shekhar, they said, had been very close to his sister and had big plans for her. "He told me he would support me in whatever I wanted to do," says Sridevi, speaking softly.

Two lanes away in the same neighbourhood, where tiny houses jostle for space with each other, another family is grieving the death of their 15-year-old, Dileep Kumar.

Kumar had failed five subjects in the board exam and, worried that he had disappointed his father, a contractor and president of the Ambedkar SC/ST Welfare Society in the area, consumed pesticide.

"Before he died, he apologised to his father, and told him he had not wanted to let him down," says Kumar's mother Veni, who has been working as a nanny in Kuwait for the last 15 years. Her husband, who she says was very close to their son, hardly speaks during our meeting.

Kumar's and Shekhar's are hardly isolated cases.

Last year, a study on suicide mortality in India published by The Lancet pointed out that suicides were the second leading cause of death among 15- to 29-year-olds (the number one cause being road accidents in males, and maternal mortality for women).

And in March, the University of Washington's Institute for Health and Metrics Evaluation reported in the British Medical Journal that suicide was the leading cause of death for women in India aged between 15 and 49 years.

India's own National Crime Records Bureau reported that there were 135,585 suicides in 2011, the latest year for which the figures are availab#8804 that's more than the number of lives lost to HIV in the same year (116,000, according to the National AIDS Control Organisation).

The figure could also be under-reported because of the stigma attached to suicides and the fact that attempted suicide is a criminal offence, though the government has begun steps to delete this section from the Indian Penal Code.

What drives them to commit suicide?

The reasons, experts say, are varied -- from loneliness and alcoholism, to depression and economic factors.

"But our studies have shown that usually, it is a combination of one or more of these factors," says H Chandrashekhar, head of the department of psychiatry, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute.

Anita Gracias, a volunteer at suicide helpline Sahai, who answers calls with a warm 'Good evening, Sahai, may I help you?', says most of the calls she receives are from people who are lonely.

"People call and ask me where they can go to make friends," says Gracias, who has been a volunteer since 2002, adding that the age of callers has been reducing. Her youngest caller is a 15-year-old.

"The number of suicide attempts among the youth in India and in developed nations might be similar, because this is the group that is at the highest risk the world over due to a number of factors, such as youth being more impulsive. But unlike in the West, the suicide mortality rate in India is much higher because here, people have easy access to lethal methods and access to emergency medical care is limited," says Vikram Patel, professor of international mental health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and one of the authors of the Lancet study.

The number of suicides, across age groups has also been increasing, points out G Gururaj, head of the department of epidemiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences.

"There has been a three-fold increase over three decades -- from around 40,000 in the 1980s to over 135,000 now. And for every completed suicide, there will be 10 to 15 attempts."

But most worrying, perhaps, is that despite these numbers, policymakers have failed to recognise suicide as a public health problem.

"India is one of the few countries that continues to treat suicides as a purely sociological or economic or political issue, when they are actually a national public health issue," says Patel.

Acknowledging this would mean putting in place a national suicide prevention policy and programme, which would include a number of interventions.

Both Gururaj and Patel emphasise that because suicide is not restricted to any particular group in terms of region, age, income or any factor, for that matter, there can be no "one-size fits all" solution.

Please click NEXT to continue reading...

There are, however, certain policies adopted by various countries that have proven to be effective. Among these would be creating awareness which would help in early recognition of the symptoms, and restricting access to lethal means, such as pesticides.

"If you can delay the impulse to commit suicide by making it difficult to buy a drug or pesticide, you can change their minds," says Patel.

"If they don't get it at the first store, it's unlikely that they'll visit more."

Countries around the world have tried this, and succeeded.

Following a rise in the number of paracetamol overdoses and deaths due to paracetamol poisoning, England passed a law in 1998 restricting the number of tablets that could be sold and reducing the packet size.

The Centre for Suicide Research at Oxford found that suicide deaths from paracetamol and aspirin fell by 22 per cent the year after the legislation was passed, while overdoses fell by 20 per cent in the second and third year.

Closer home, Sri Lanka, which once had the highest suicide rates in the world, managed to reduce it by half in two years by restricting access to pesticides, says Patel.

In India, meanwhile, 15-year-old Kumar could kill himself by buying a pesticide used against bed bugs from his neighbourhood grocery store for Rs 35.

There is also insufficient research into suicides in India, says Gururaj.

"It's a hidden phenomenon. Nobody wants to invest in research because there is no profitable drug that's going to come out of it."

Other countries, says Patel, have managed to bring down their rates of suicide and there is no reason why we can't either.

"Unfortunately, we just discuss and debate the issue, instead of doing something about it."

Warning signs of suicide

Steps to reduce number of suicides