The Festival of Lights is special for Sikhs too, finds Arthur J Pais.

When G P Singh, an engineer and would be community leader, arrived in San Antonio, Texas, 34 years ago, he was not only the first turbaned Sikh in the city but also among very few Sikhs.

“We celebrated Diwali with our Hindu friends,” Singh, who is also active in the mainstream community as a philanthropist, says of this week. “But with more and more Sikhs coming to this city -- now there are over 1,000 and a second gurdwara is coming up -- we have our own Diwali and langar.”

For devout Sikhs, Diwali is celebrated not just as the triumph of good over evil in the life of Ram and Sita -- who they will proudly say are mentioned hundreds of times in their scriptures, especially Ram in the Guru Granth -- but also the triumph of their sixth guru, Hargobind.

“He not only won freedom for himself, from the Mughal ruler, but also made sure he could free at least 52 captive rajas who were Hindus and who were held as political prisoners,” says Singh, recalling history of the early 17th century. Guru Hargobind had stood his ground. But Emperor Jehangir, who had come to realise that the religious fundamentalists who had been behind the martyrdom of Guru Arjun were a greater threat to his throne, wanted to release the guru.

Guru Hargobind wanted other political prisoners be released too. “Legend has it that the emperor told him he could take as many people as those who held to his robe and he extended the robe in such a way that 52 could cling to it,” Singh adds.

“I am an engineer and finding creative solutions to a problem has interested me all along,” he says. “And here was our guru who was not only creative but also cared for justice and fairness. So celebrating his life example gives the Sikh Diwali a tradition of its own. With the growth of the Sikh community in this part of Texas we could also have our kirtans and remember the teachings and examples of our gurus.”

The Bandi Chhor Diwas (The Freedom Day), as the occasion is known, may not be the most important Sikh festival, says Rahuldeep Singh Gill, a professor of religion in California. The birthdays of Guru Nanak and Baisakhi (spring celebrations) are more important but this day is commemorated with pride and the remembrance of the need for justice and humanity. Guru Hargobind, a freeman, returned to Amritsar from the Gwalior prison on the Diwali day, according to Sikh history.

The festival in India falls around the time of the second yearly harvest, he says. “A large number of Sikhs are agriculturalists and marking the Bandi Chhor Diwas has a special significance to them,” he added.

Hundreds of Sikhs, who migrated to Canada and then to America in the first decade of the last century, were also agriculturalists. Hounded by racism and xenophobia from state to state, farm to farm, often marrying Mexican Christian women, they were not in a position to publicly mark Baisakhi or Diwali.

Things began to change in the late 1960s, especially with the rise of the Civil Rights movement, the descendents of the early Sikhs say. And the festivals of Indian origin started being celebrated openly.

‘There was a time, we used to shut our windows and doors and mark the Baisakhi or Diwali,’ a son of first generation Sikh settlers in Sacramento, California told a reporter not long ago. ‘But today, we proudly mark our heritage and we throw all windows and doors open. Let the world know of our culture, our religion and our food.’

There are over 500,000 Sikhs across America. The Diwali season is one of the busiest times for them. They, especially those who are married to Hindus, also mark Diwali festivities with their Hindu friends. And they have their own gurdwara celebrations.

“I would be surprised if any Granthi will not recall the story of Ram and Sita, the stories of valour, sacrifice, courage and repentance,” said Tejinder Singh Bindra, a prominent Sikh organiser in the New York tri-state area, whose family has instituted the biannual Guru Nanak Prise for ecumenism. “Anyone familiar with our holy book knows how many times Guru Nanakji has invoked the name of Ram,” he added. “This is the time for not to just pray for a better life and prosperity, but also renew our spiritual orientation, and celebrate the triumph of good anywhere.”

Sonny Singh, a musician and a grass-root community organiser, who calls himself a radical, uses occasions like Diwali and Bandi Chhor Diwas as a reminder for self-renovation and commitment for social justice. A member of the Red Baraat band, based in Brooklyn, New York, he says his faith has made him a stronger fighter for justice in the mainstream community and work for marginalised people of many faiths and ethnicities.

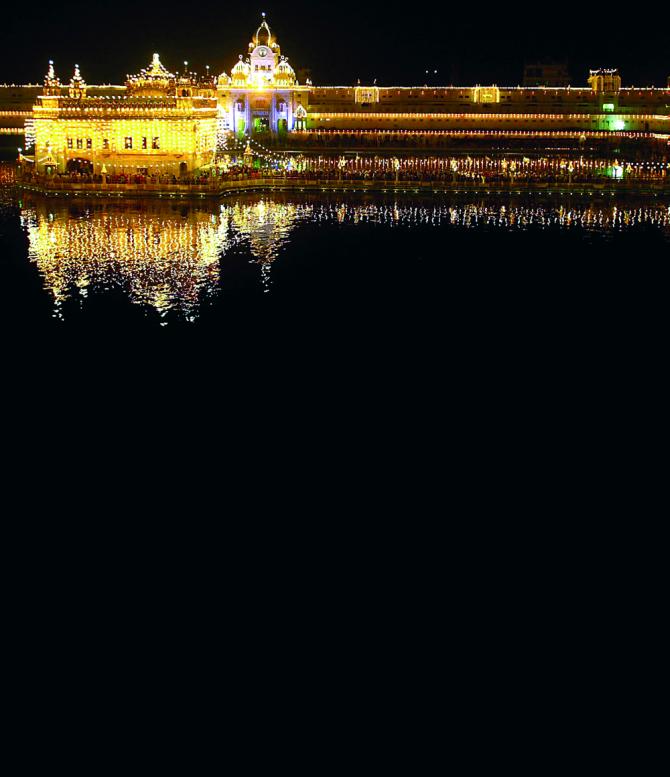

Like many Hindus and Jains who mark Diwali, Sikhs also feel they cannot have fireworks freely across America as their kith and kin in India. Many Sikhs say their fond hope is to be in Amritsar not only for Baisakhi but also for Diwali when their holiest temple is lit in a spectacular display. “Dal roti ghar ki, Diwali Amritsar ki’’, said one quoting a popular saying. (There’s nothing like the home-made food, and Diwali at Amritsar.)

Major Kamaljeet Kalsi would be taking off couple of days from his army base to mark the two festivals with his family and friends in New Jersey. He will also visit the gurdwara near his home, seeing it lit for the festivities and his family could join the langar volunteers.

“It is significant that the two festivals are held around the same time,” he says taking a few minutes off his 24-hour long ER practice. “In Diwali and Bandi Chhor Diwas, we mark the triumph of good virtues. And that is also a constant reminder to us what Sikhism is about. Guru Hargobind, in particular, fought not only for his Sikh heritage and identity but also for the welfare of non-Sikhs. And that means even today we have to carry out his legacy, as that of Guru Nanakji in embracing good influence of other faiths and remind ourselves that as Sikhs we ought to not only look after our own but fight for justice and goodwill for everyone.

“Diwali and the Bandi Chhor Diwas remind us every year who we are and what we ought to be. In these times when there is so much of a division and mutual distrust, we should mark these festivals with humility and the best of intentions for all our fellow human beings.”

Isn’t it a wonderful thing, muses Kalsi, that the Sikh festivals hail two men who had both released abducted people?