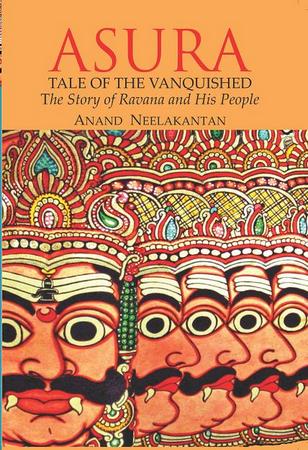

Anand Neelakantan tells Aparna Sundaresan of YouthInc just why he chose to narrate the Ramayana from the point of view of its villain in Asura -- Tale of the Vanquished: The Story of Ravana and His People.

Asura -- Tale of the Vanquished: The Story of Ravana and His People is the Ramayana told through Ravana's perspective.

No one in this tale, not even Ravana himself, is either god or devil. Instead, every character is human, only differentiated from the other by their caste and love of power.

Thus, terms such as Devas and Asuras which are otherwise connected to notions of divinity and evil are only different castes with no other associations of perceived morality.

What author Anand Neelakantan achieves is a deconstruction of the Ramayana myth to a more relatable and plausible chain of events, reminding us that legends of gods and such are only machinations of age-old politicos and the powers that be.

This 'Ravayana' is a fascinating interpretation of the Ramayana epic. One only wishes it were written with more finesse to hold the reader's attention better.

Why Ravana and why the Ramayana?

Ravana as a protagonist offers immense possibilities. His life itself is an inspiration, among all the conventional Indian mythological characters. Apart from Duryodhana, who is far less complicated, few characters in Indian mythology offer so much challenge. Who was Ravana?

He is not a run-of-the mill villain. He is a ruler about whom Rama talks in glowing terms. Rama tells Lakshmana to learn the art of governing from Ravana, when Ravana is in his last moments.

There is another folk story where it is told that Rama needed the most scholarly Brahmin priest to conduct a yajna before commencing the war. When he enquires, everyone tells that the most scholarly Brahmin alive is none other than Ravana.

Rama sends an invitation to Ravana to come and conduct the yajna to defeat Ravana. Ravana arrives at Rameshwaram and conducts the yajna and blesses Rama before war for his success.

I have not used this story in Asura, but such stories are not told about any other mythological character. A consummate Veena player, an astrologer, scientist, authority on medicine, musician, artist, warrior, great administrator -- I do not think any villain has been portrayed with so many qualities in any story.

It is such a villain that Indian folk traditions have been celebrating for the past thousands of years. I think that answers your question of why Ravana sufficiently.

Courtesy:YouthIncMag.com

How much and how long did you have to research before writing the book?

One cannot measure a book in terms of how long it took. It is not like the author keeps a stop watch and a calendar and writes.

Asura is a work of passion which has taken my entire life to write. I have been exposed to mythology right from my childhood and Ravana's story is something that has always fascinated me. As I grew up, I got exposed to various traditions and folk tales of Ravana.

The novel happened by itself. It took six years to bring it to the current form, with lots of breaks for travel and research in between.

Did you come across any surprising revelations during your research?

Everyday was a surprise. The richness of our mythology and tradition is beyond imagination. Every community, every tribe, every village has many tales to tell and the versions of Ramayana or other stories vary from village to village and even from the narrator to narrator.

This variation is what makes us the greatest story telling nation of the world. We have not restricted the creativity of people with dogmas and fundamentalism. One of the most surprising revelations was hearing about Moppilah Ramayana or Muslim Ramayana of the Malabar where Rama is Lama and is a Sultan instead of the prince of Ayodhya.

In another, Sita is a tribal princess for whose hand both Rama and Ravana fight. One of the Kannada versions says Ravana is the mother of Sita, yes, the mother, and another one portrays Rama and Ravana as brothers. The sheer variety is mind boggling.

When you set out to write the book, how did you plan the entire narrative?

I have a rough plan of the plot. But once I sit with my laptop, the characters lead me to their story than the other way round. I only control the general layout of the plot and I give freedom to my characters to evolve, narrate, talk and take the story in whichever way they want as long as it does not leave the general plan.

Some authors plan every line before they write it. I prefer spontaneity to detailed planning. May be I am disorganised, but it gives me more pleasure in writing.

One of the most appealing things about the book is that nobody is a god and nobody is a devil. Why, in your opinion, do we Indians deify everyone and everything?

Indians have been conditioned to deify everything and everyone from childhood. Having respect for others is a very good thing. Finding divinity in animate and inanimate things is also a very good thing. One of the most beautiful poems in the Rig Veda praises Ushas, the goddess of dawn. But that did not stop our ancestors in applying a very rational mind to life's problems.

The essence of the Upanishads is questioning. The quest was important, the doubt was essential. Of the six systems of philosophy or Darshanas, three deny the existence of God. In ancient literature, we find arguments and counter arguments questioning every kind of thought. Buddhism and Jainism are essentially rebellions against the supremacy of the Vedas.

If see all these things, we can see that the great schools of philosophies we Indians developed are a product of a very confident people who were sure of their intellect and capability. When Ramayana and Mahabharata were written there was no deification of Rama and Krishna.

Deification started when the cultural collapse began. Even Buddha who was silent about God became a god. Mahavira became a god. If we read our history correctly, deification was an off-shoot of the Bhakthi movement, which in turn was a product of the serious threats faced by our country and way of life by the repeated invasions during the middle ages.

The benefit of deification was that it formed a wall of defense against an Islamic overrun of India. Deification in itself was a rebellion against monotheistic Islam. True, common people have always deified nature and objects like trees, but Bhakthi movement gave respectability and intellectual approval for deification of all things. Debate and dissent vanished. The questioning stopped suddenly. Hinduism became more rigid, more caste oriented, more ritualistic as it was withdrawing into its shell.

The change from this came first in Bengal renaissance of 19th century, when intellectuals started questioning the tradition. This was again simulated by the collapse of Islamic rule and the dawn of another threat, that of Christian missionaries. Initially, when the British rule started, society withdrew further into its shell, but later when English education spread, its confidence grew.

Society understood that it required new defenses and the reformers borrowed heavily from the new religion to counter its threats. This reformation of our society continued and the movements against social evils like untouchability, Sati, child marriage etc. were spearheaded by great rebels (now they are called reformers) like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Vivekananda, Gandhiji, Ambedkar etc.

The period of deification was over, or that was what everyone thought. But in the 1990s, a new wave of deification and fundamentalism swept the country. This was again a reaction to a collapsing society in the grips of poverty and the threat of a total breakdown due to caste politics.

National confidence was at its lowest, with the country pledging its gold for making ends meet. We see that whenever our society faces a threat, it withdraws to fundamentalism and the deification of certain men, events or places. Whenever society becomes confident, it questions.

This is a cyclic process. The economic success of the last two decades has given more confidence to our society. The questioning process has already started. Asura is just a small part in this big process that has just begun.

In a religious country like ours, how important is it to deconstruct myths? One of the dangers of deconstruction is an instant uproar from the more fundamental religious quarters. How do you manage with that threat?

A confident country can afford to deconstruct myths. That is how a country or civilisation progresses. In medieval Europe, people used to be burnt at stakes for the slightest dissent from the church. Europe was living under the stress of the Crusades, plagues and economic upheavals.

Later, with economic prosperity, the grip of fundamentalism and the church waned. Now the church has become irrelevant in the west. Nobody took Charles Darwin to task for suggesting the theory of evolution just because it made the creationists look like a bunch of blabbering clowns.

Their society had become confident by that time. Remember that poor Galileo had to apologise for suggesting that the earth revolved around the sun, a few centuries ago. The same is true about other communities that look very fundamental now and resort to violence. I think we have gained enough confidence to accept differing points of view.