Photographs: Courtesy Upasana Mataki's Facebook page Vatsala Chhibber, YouthIncMag

What inspired 24-year-old Upasana Mataki to quit her corporate job and launch the country's first lifestyle magazine in English for the blind? Read on to find out about the young entrepreneur's courageous decision and the challenges she's faced so far...

Upasana Makati, a BMM graduate from Jai Hind College in Mumbai, was dissatisfied with her job as a public relations officer.

On completing her graduation, Makati received a scholarship and left for Canada to study communication.

Upon returning, she secured a job with a public relations company in Mumbai, but something didn’t feel right.

"I always wanted to do something different. I always felt this vacuum when I worked at a PR agency. That’s when I started thinking about different ideas that I could explore," confesses Makati.

This dissatisfaction eventually gave birth to White Print, India’s first magazine for the visually challenged.

In the interview that follows, Makati tells us how she came about launching the magazine, fighting the challenges and emerging a winner.

Why did you decide to start a lifestyle magazine for visually challenged people?

The idea struck me one day when I thought that if I had to list publications that I could read in my leisure time, there are plenty of options available, based on different languages and interests.

But when I thought about a visually impaired person, no name came to my mind.

That is when I started researching and asked someone to connect me to visually impaired people.

When I started talking to them, I realised there were not many publications and that they were waiting for something eagerly.

I went to the National Association for the blind and spoke to them.

Initially, they were wary of the idea of a 24-year-old starting something like this.

They had their apprehensions whether things were ever going to move forward. But I was not discouraged by their response and I decided to move on.

What were the hurdles you had to overcome while setting up the magazine?

It took me eight months to get a title because in the Indian system, there is always room for error.

They rejected my title twice.

In my third attempt I got my title registered as White Print.

I had taken up random freelance jobs and was writing for websites and editing entertainment magazines just to keep the ball rolling, just so that money came in and I could invest that into basic government activities.

After I got the title registered, even NAB offered to support me.

They said, 'people would love it because they don’t have any options; you’re giving them a monthly magazine right at their doorstep, they would definitely want to take it.'

Courtesy:YouthIncMag.com

Please click NEXT to continue reading...

'We have these misconceptions that stop us from thinking that the blind lead a normal life'

Image: For representational purposes onlyPhotographs: Eddau/Wikimedia Commons

How did you narrow down on the content of the magazine?

We thought of coming out with a lifestyle magazine and decided to have a good mix of things such as food, fashion, travel, etc.

We also included short stories because we wanted to add a literary element to the magazine as there are not many novels available in Braille. We also have success story interviews because we realised that the visually impaired wanted to know more about their own community.

We also do a lot of interviews in terms of music because music is something they love, and also film features.

We tend to think that they might not know about films but one girl told me Katrina Kaif was her favourite actress as she loved her voice.

Another girl told me that she accompanies her friend to the theatre to watch movies. We have these misconceptions in our minds that stop us from thinking that they lead as normal a life as any of us would.

One girl who loves shopping, has a sort of a stick, like a pen. When you put that pen on a particular texture, it tells you what colour that is.

We also have a readers’ section where we invite visually impaired people to send whatever they want. We give them a platform and that has been a very popular section.

You’ve said that White Print is not a charity venture. How do you plan to make money from this enterprise?

We have not promoted ourselves as a charity venture because when we were speaking to visually challenged people, they said they were done being sympathised with.

They don’t want to be looked down upon as a community that cannot afford. We charge a very nominal amount (Rs 30 per issue) and totally bank upon advertising revenue.

For our first issue itself we got Raymond on board.

A lot of people wonder how ads are going to be in Braille because advertising has always been about graphics, colours and text.

Raymond was the first one to try it.

It was a big challenge for me to change that perception and convince people to advertise for a very, very marginal community in the country.

Raymond contributed a five-page article about their spring-summer collection, an advertorial.

We are in the process of speaking to a lot of big companies to convince them.

What is the reaction of advertisers when you approach them with the idea of Braille advertising?

A lot of people wonder how we are going to design an ad for them because they want their product packaging, etc in a print ad while in Braille you can make very simple squares.

Some people would have a big question mark on their faces; somebody didn’t even know that Braille is a combination of six dots for the visually impaired to read.

These are people who work at higher positions and when they don’t know what Braille is, you can’t blame small localised brands for being ignorant.

It has been a challenge and we are asking people to cater to this community as well.

'If you're prepared to take the harder route, you can definitely make a mark'

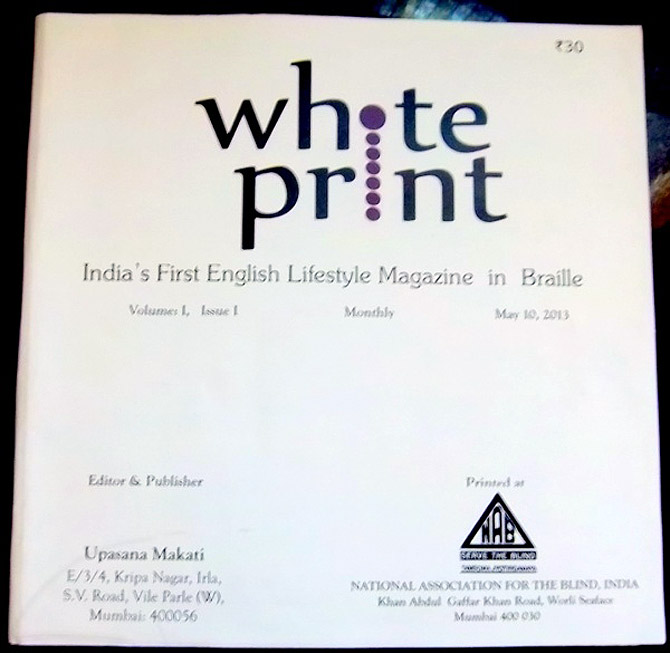

Image: Cover of White Print's first edition launched in May 2013Photographs: Courtesy Upasana Mataki's Facebook page

What plans do you have for the future of White Print magazine?

My first aim is to ensure that the magazine reaches out to maximum number of people.

There are 56 lakh people who are literate in Braille in our country and I want to see most of them subscribe to my magazine.

Post that, we would love to come out with another magazine in the same space, maybe on some other topic of interest, but definitely something to do with Braille and the visually impaired for sure.

For those who are hesitant to leave behind a secure, financially lucrative career for a social endeavour, what advice would you offer?

I wouldn’t advice, but I would just say it is very important to follow your dream.

The atmosphere is so cluttered right now that you have to think out of the box, think differently.

There are ways in which the two could be brought together.

It’s about how you want the world to see what you do; it’s about how you want others to perceive you.

Once that’s clear in your head, you have to be dedicated.

I could have given up the second time when I didn’t get my title. I could have paid an advocate Rs 20,000 to get it done.

But we didn’t want to take that route, we wanted to do it ourselves.

That dedication is sometimes missing in a lot of people.

If you are prepared to take the harder route, you can definitely make a mark for yourself and help people and society.

Contributors to White Print include renowned journalist Barkha Dutt and stand-up comedian Sapan Verma

Comment

article