After she failed in her grade ten examinations, Aarti Naik would've ended up being a domestic help like most of her classmates but chose to fight the situation she was in. Today she teaches schoolgirls from her neighbourhood for free lest they fail in their examinations and in life.

Sometime in June 2003, when she received her State Secondary Certificate (SSC) examination mark sheet, Aarti Naik was crestfallen. She had failed in two subjects -- Social Sciences and Maths.

Her father, Dattatreya had enough of these new fangled ideas about educating the girl child. So he did what he always wanted to do -- he put a stop to her education.

During the next three years Aarti Naik stayed at home. She rarely stepped out of the house -- her father was dead against the idea of women crossing the threshold -- and spent most of her time making flowers out of satin ribbons.

Three years later, she decided to re-appear for the papers she had failed in.

When the mark sheet came out, she couldn't believe it was hers.

Aarti Naik had scored 70 on 140 in Maths and 110 on 140 in Social Sciences -- the most she'd ever seen in her life.

As she convinced her father to let her study further, she realised her greatest weakness was that even though she knew what she had to study, no one taught her how she should go about it.

So, in September 2008 Aarti Naik decided to start a free-of-charge coaching class of sorts where she could teach schoolgirls from her locality to learn better.

Today, the organisation aptly called Sakhi (or confidant) is almost three years old and operates from Naik's home itself.

It has 28 students, whose life it directly touches.

But in little and unknown ways it is also touching the lives of Aarti Naik and her family and those of the families around her.

This is her story.

You can reach Aarti Nain here: aartidnaik@gmail.com

The sky is overcast and there is a slight drizzle.

I am standing in the middle of the slightly wet road with half a dozen dumping trucks loaded with the city's trash rolling into the local dumping ground on one side and a funeral procession on the other heading to the Hindu cemetery nearby.

The overpowering stink of the trash and the dead is unbearable.

From a distance I notice Aarti Naik waving out to me. She's taken shelter in a local grocery store.

We shake hands -- her handshake is firm -- and proceed to her house located not very far from the cemetery and the dumping yard.

Khare Chawl is part of a huge squatters colony with rows and rows of houses divided by single-brick walls.

A two-feet walkway that also has an open sewage running on the side divides each of these rows.

Aarti Naik walks briskly, jumping over puddles and greeting the few women who look curiously in our direction.

At one point, she turns a corner and disappears. A moment later she comes back realising I was lost.

Around the corner is her house -- a 15x15 ft almost windowless room divided into a 'living area' and a kitchenette that also has a bathing space.

This was the house she was born in, she says, and for the longest time only world her mother, Pushpa has known.

Aarti Naik's father Dattatreya is a turner, someone who constructs machines that make cloth labels that are stuck under the collar of your shirts.

He hasn't, however, made a lot of those in his lifetime.

In the last 35 years, Aarti tells me, he has worked for a little over two years.

Their house runs from the rent of a store her father bought years ago, perhaps his only intelligent investment decision.

When she failed in her standard ten examination in 2003, Dattatreya Naik banned her from studying any further.

"What is the use?" he reasoned. "Someday you will get married and go elsewhere."

And so at a time when girls Aarti's age had stepped out of their cocoons into a life full of promise and started going to colleges Aarti was restricted to the four walls of her almost windowless home.

Dattatreya Naik is a wiry old man in whose worldview women are a burden on the family, aren't to be educated and palmed off on any man willing to take them in marriage, preferably without a dowry.

His wife and Aarti's mother Pushpa wears a huge vermillion mark on her forehead and like all mothers I know, offers me tea the moment I step into the house.

The 'organisation' (for the want of any other word) Aarti runs is on the second storey or rather a loft -- a part of the house that wasn't there till about a year ago.

This is where 28 girls from the neighbourhood gather each evening, six days a week to study. Or rather, to learn.

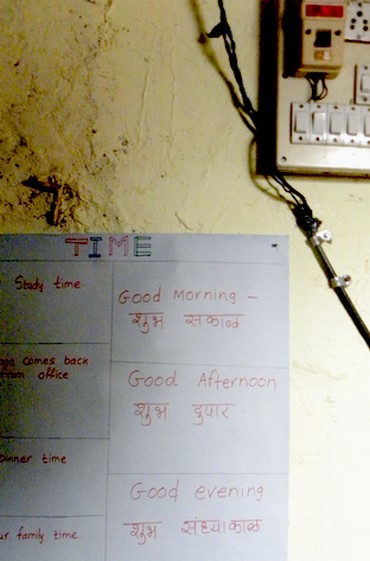

The walls of the loft seem freshly painted and have handmade charts. There are letters of the alphabet, forms of greetings in English and that beloved nursery rhyme about the cat who scared the little mouse under the queen's chair written in the Devanagari script.

There's also a cane bookshelf in a corner that is just about beginning to see thin books piled one on top of another. Most of these books are on Basic English for young children but there are others that inculcate values through stories and even others that encourage little ones to read.

This is Sakhi (the word can be very loosely translated into English as 'a female friend and confidant') a place that the girls call their own.

***

The idea of Sakhi came about one afternoon as Aarti sat poring over her books while still in her class 12.

She'd been through hell trying to get her head around the algebra formulae and making sense of social sciences.

The three years she'd been banned from studying, Aarti would spend her days making flowers out of satin ribbons. It earned her Rs 9 each day. The task was arduous.

It required her to use a sharp pin and fold the ribbons in a particular manner so it would make it look like a flower. She would then use these flowers to make a garland.

She would work for hours straining her eyes, ignoring the bruises the pin would cause.

For all of this, she would be paid Rs 9.

Sometimes she'd sit in the bathroom draw the curtains, switch on a tiny lamp and work through the night so she could earn a few bucks more.

When she had saved up some money, she opened a savings account in a local bank and started putting away whatever she would earn.

One day, she discovered she'd saved up Rs 4,000.

Her future didn't seem as bleak as it had when she held her mark sheet three years ago.

Aarti Naik had found hope for a new life, nine rupees at a time.

Her father though remained unmoved. He would rather be dead than see his daughter step out of the house again. But for three years, she'd let him control her life and now she'd have none of it.

Ignoring her father, Aarti re-appeared for the examinations.

Two months later, when she received her marksheet, Aarti Naik was over the moon. She'd scored 70/140 in Maths and 110/140 in Social Sciences -- they very subjects she'd failed in!

Two years later, she completed her higher secondary certificate examination too.

When she was studying for this exam, Aarti Naik realised that her greatest weakness had been lack of proper guidance.

"All through school, I was taught to rote learn. I'd rarely understand and assimilate. Reproducing what I read in my words was unheard of till then," she says.

The idea had begun to take shape. Aarti did not want other girls to go through the same travails as her.

"Municipal schools tend to freely promote their students, especially girl students, so they can get them off their hands as soon as possible. The problem is when they reach the tenth standard. That's when they fail miserably, like I did," Aarti says.

"But unlike me not everyone may have the will power to go on. Many of my friends who failed stopped studying. Today they are either sitting at home or are working as domestic helps. I didn't want that future for these kids."

So Aarti approached an NGO -- Ashoka Youth Venture -- for funds.

"It was an open forum where I had to present my ideas. That was the first time I had stepped out of Mulund (where I stay) and gone to Dharavi. It was like travelling to another city. I took two of my friends with me. Hesitant at first, I began telling the people there about my ideas. They seemed to be impressed."

Soon after, Aarti travelled to another place that she'd never heard of -- Tata Institute of Social Sciences from where she collected a cheque for Rs 5,000. She'd won a grant and it was the first time she'd seen so much money.

"I trusted my friends and I transferred the money into their account. Once they got the money, they had different ideas. They said we could start mehndi classes! I didn't want to start mehndi classes. I wanted to educate young girls."

Soon after, she realised that they'd used up almost all the money.

"I was really upsetc And I felt I was cheating the people who gave me the money. So I told them about it and one of them intervened. Finally, I only got Rs 900 back from them."

From the Rs 900, Aarti bought some chart paper, stationery and a basic set of books and started out.

Her father, who was already fuming at the idea, was told that this was part of her college curriculum.

"It took me a month to convince him," Aarti recollects.

On August 13, 2008 Aarti Naik met up with six sets of parents and told them that she wished to teach their children and not charge them for it.

"As long as their children were off their hands, they didn't care what they were doing. So they agreed."

Meanwhile, having completed her HSC, Aarti opted to complete her graduation from Yashwantrao Chavan Open University so she could plan out her classes.

At Sakhi, Aarti teaches them basic English and focuses on reading and writing. She encourages them to understand what they read and asks them to narrate or write down what they understood.

The kids are engaged in simple letter games like one involving a set of homemade cards -- each carrying a letter of the English alphabet, which they must arrange in the proper order.

Aarti also ensures that they interact with each other in English, a language that is rarely spoken in the neighbourhood.

For a year the six girls and Aarti would huddle each evening and study. It was as much a learning experience for the girls as it was for Aarti.

It taught her that there was a lot she had to learn too. So she started taking English lessons herself.

"I don't speak good English but I want to. There are books I read, classes I attend so I get better. That way I can teach them better," she says.

At the end of the first year, she decided to show what the girls had learnt. So she organised an event where the girls came on the stage and simply spoke.

"Someone spoke about their mother, another girl spoke about Savitribai Phule, someone else talked about Ambedkar. We even played out a skit.

It wasn't anything great but we got the point across. Parents who thought their girls were demure and didn't talk much were surprised to see how confident they were outside of their homes. Others realised that their children had something to learn too."

At the end, Aarti took the microphone and narrated her story. She told them about her failure, the nights she spent working and earning a measly sum just so she could fund her education.

Later that evening more parents came to Aarti with their daughters. Today, that number has swelled to 28.

Last year, Aarti received a grant -- a sum of Rs 20,000 from another NGO Life Unlimited. She'd proposed to make a loft to accommodate the increasing number of students.

Yet again, her father came in the way.

"It was funny how I approached it though," she says in retrospect laughing. "I told him that I had received a scholarship of Rs 15,000. And all he had to do was spend another Rs 15,000 and we could make a loft in our house! When I put it that way, he loved the idea!"

All of 10, Sakshi Kanudolas peeps over the partition on the main door before scampering away to play.

Sakshi has been one of Aarti's students for two years now. Her mother Pushpa is Aarti's friend. Unlike Aarti, she gave up education after seventh grade. Her husband abandoned her a little after Sakshi was born.

So Pushpa returned to her parents' home much to their displeasure. Up until a few years ago, she worked as an aayah (maid) at a hospital till her health deteriorated. Since then, she's been at home, a situation she's resigned herself into.

Even as the mother sits with a slouch, life having sucked the spirit out of her, Sakshi has a twinkle in her eyes, one that Pushpa hopes doesn't die.

Till a couple of years ago before she joined Aarti, Sakshi didn't know how to read or write -- not even in Marathi, let alone English.

This, despite the fact that she was in her second grade in a local municipal school and had technically passed at least half a dozen examinations before being promoted.

No one so much bothers about whether the students are attending the school let alone find out how they're faring in their examinations.

I am told the municipal school that another of Aarti's students, Pooja and her friends attend, didn't even tell them what their syllabus for the final examinations was.

"No one even seemed to know when their examinations started. I learnt about it when Pooja said they were 'writing on some papers'," Aarti says animatedly.

Aarti, who plans her own studies and those of her students according to their examination schedules, dashed towards Pooja's house and asked her parents if they knew their daughter was in the middle of her annual examinations.

The parents of course did not have a clue.

"Most parents here don't care about what their child studies," Aarti says, "As long as their children don't bother them, they're fine. It is only after some time, when they see their children speaking out or reading books that they realise they're doing something productive after all."

Aarti's greatest challenge today is trying to get the parents involved in their children's life.

She tries to overcome it by interacting with them as often as possible, at least once every couple of months, and telling them of their child's progress.

Once every month, she goes to each of their homes and hands them over a book that they must read and return the following month.

Some parents are seeing a difference in their children. Pooja's mother has seen her change from a quiet introvert not very good at her studies becoming more confident and taking more interest in academics. Her younger daughter Pradnya stood first in her class, a feat the mother still cannot get over.

As for Aarti Naik, she is yet to complete her education. Last year, she almost did.

When she had to pay her fees for the final year of graduation Aarti realised she was Rs 1,000 short.

During the year that followed she and her mother managed to save up the sum.

So now, sometime next month, Aarti Naik will step out of her house again and fulfil the dream she'd seen for herself.