Meet Indian-American Aysha Bagchi who is perhaps the most traveled of the 32 Rhodes Scholars for 2012. She shares her journey here.

She worked as a grocery store checker and entered high school contests in Austin with prize money to finance the trips to England, Israel, the West Bank, Malaysia, China, France, and Italy. Aysha N Bagchi, daughter of Uttarayan Bagchi, professor at the University of Texas at Austin, and Gail Nicholson, a lawyer, is perhaps the most traveled of the 32 Rhodes Scholars for 2012.

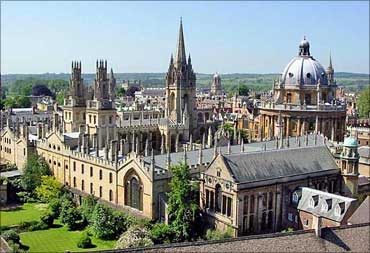

She is studying on a highly prestigious scholarship at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, taking classes towards a graduate degree that support her political theory research into the Israeli school system. As a Rhodes Scholar, 22, who earned her bachelor's degrees at Stanford in philosophy and history with honors in ethics in society, plans to pursue a doctorate of philosophy in politics at Oxford.

I have always been interested in social policies, public health and social service. I lived for a few days in the Arizona desert with an organisation helping the immigrants, who had slipped into the desert, with basic needs like water.

Hundreds of people die in the desert because of hunger and thirst and not many people are even aware of this. Back on campus, I designed and taught a course at Stanford on immigration in the winter and then led the 11 students on a spring break trip studying immigration in Arizona's desert and cities.

This led to the formation of the Stanford Immigrant Rights Project. I am no more at Stanford but I know it has become a thriving awareness, advocacy, and service group and has over 25 active members who help immigrant service organisations in Palo Alto around the campus and nearby areas providing health care and English language to immigrants.

Along with a few other members, I helped successfully petition Stanford President John Hennessy to publicly endorse the DREAM Act, a bill that was to aid undocumented students. (California has since passed its DREAM Act).

You are also known for your advocacy writing during your Stanford years.

At Stanford, my proudest contributions have come in aiming to promote a holistic undergraduate experience for students who, no matter whether we work in Washington, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, or beyond, will be called upon as global citizens.

In the context of an increasingly commercial and specialised world, I have used my writing in The Stanford Daily and my service on the task force reviewing Stanford's undergraduate education to advocate for an intellectually and personally transformative education, one that engages students' philosophical and value-laden identities as well as our technical skills.

In (historian) Tony Judt's words, I have tried to promote an 'ethically informed public conversation' about education at Stanford, aimed at fostering an ever-more reflective and responsible student culture.

In my application for the Haas/Koshland Memorial Award, I described how the 10-day visit to Israel I made just before college with leftover high school earnings led me -- a student who did not grow up with personal connections to Israel -- to dream of spending a year there.

A handful of my experiences included climbing the Mount of Olives overlooking the Old City, talking with an Arab mother and daughter as they walked on their way to the Temple Mount, witnessing prayers quietly whispered at the Western Wall, spending three hours in Yad Vashem, touching the star marking Jesus's birthplace in Bethlehem, visiting the outskirts of an Ultra-Orthodox Jewish neighborhood in Jerusalem, and living casually amidst a seemingly pervasive military presence.

Although I could not articulate precisely why, I felt as if I were at a gravitational center of the universe. In a sense, Israel is a boiling pot epitomising so many of the complexities that make us human. The Haas/Koshland Memorial Award is giving me the chance to make a new home in that world.

In my Rhodes essay, I wrote that the Middle East is a place where I see many penetrating lenses into important global questions.

For instance, the religious and cultural segregation in Israel's school system, which is leading to professional and political crises, provides a striking portrait of the potential tensions between child interests, parent interests, and the health of liberal democracies.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict provides a powerful look into the roles of religious differences, border disputes, and terrorism in global conflicts. The pilgrims in Jerusalem help us to think about what freedoms government was created to protect.

What is it to be an Indian American?

I am the youngest of two daughters. My older sister Dia is a scientist. Our father never said we should follow any particular career. He likes to travel and from him I learned that travel was also an educational experience. I have been to India with him and by myself many times. I have also volunteered as an English teacher in Hungary.

What will you be doing at Oxford?

My desire to complete an MPhil in politics (political theory) at Oxford -- a program that combines the politics and philosophy departments -- to have a deeper grounding in the philosophical debates that center around questions of justice.

In my later career, I want to encourage a public dialogue that approaches social, political, and humanitarian challenges with an emphasis on what Harry Truman described as 'the moral nature of man's aspirations'.

I want to encourage a dialogue that is motivated, first and foremost, by the question: 'What is just?' Oxford's program will help me gain a better mastery of the history of liberal thought and contemporary theories of justice.

Judt writes primarily to a rising generation that he sees as acutely worried about a host of national and global concerns: An intensifying fear of terrorism, shaken confidence in global financial markets, anxiety about our environmental future, and, more broadly, a sense that we lack common societal purpose beyond promoting economic growth.

In the midst of these and other challenges, Judt emphasizes the urgent need for the return of an "ethically informed public conversation", one in which we respond to a judicial decision or legislative act by asking questions such as: Is it good? Is it just? Will it bring about a better society or a better world?

I came to college as one of the students Judt describes, anxious about societal challenges and wanting to get involved. I planned to study political science or public policy, the majors that seemed directly concerned with important national and global problems.

Yet an introductory political science and philosophy course during my first quarter shifted my academic trajectory.

Introduction to political philosophy placed my public policy concerns within a world of deeper questions: Why do we have authority and the rule of law? What are a citizen's obligations in that context? What would a just society look like? What forms of freedom and equality do we seek to advance and how can those ideals be reconciled? The class forced me to grapple with the foundational questions that motivate the policies we fight for.

And so I began a college career in which I was often grappling with questions about the good society and the good life. I came to love exploring the past as well, discovering how studying and constructing historical narratives can similarly provide a deeper lens into policy concerns.

In my research, I applied these abstract fields to practical questions. For example, I spent a summer at the US Library of Congress examining the histories of US and French hate speech policies in order to understand our present differences.

My senior thesis navigated the philosophical terrain of competing child, parent, and state interests in education to develop a legal theory for handling the rapidly increasing number of US parental disputes over whether to homeschool a child.

While teaching English in two villages in Hungary, I gained insight into the lingering disillusionment from Hungary's years under Soviet rule and witnessed the country's difficulties in integrating its Roma population.

These experiences prompted me to reflect on the conditions that help societies become forward-looking and to consider the challenges facing multicultural democracies.

I plan to work either as an opinions journalist or in public office, two areas in which I see the opportunity to be a public voice on political, social, and humanitarian issues.

Excerpted from Aysha N Bagchi's Rhodes Scholarship essay