A new study aimed at finding the difficulties working parents faced while balancing their families and offered solutions.

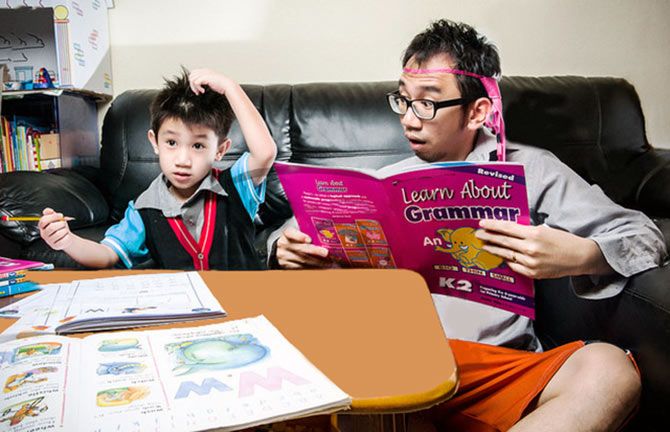

Photograph*: Sonador Arte Studio/Creative Commons

Busting the conventional notion, a recent study has found why 9 to 5 isn't the only shift that can work for busy families.

The study from the University of Washington focused on two-parent families in which one parent works a nonstandard shift, hours that are common in health care, law enforcement and the service sector.

The study found that the impacts of parent work schedules on children vary by age and gender, and often reflect which shift a parent works.

Rotating shifts -- a schedule that varies day by day or week by week -- can be most problematic for children.

"Workers often struggle to carve out the work/life balance they want for themselves, and in dual-earner families, balancing partners' schedules remains an issue for many families," said Christine Leibbrand, author of the study. "Parents are facing these decisions of balancing work and caring for their children."

Nonstandard schedules, especially for single-parent and lower-income families, are associated with behaviour problems among children, according to past research.

To add to that research, Leibbrand examined data on two-parent households in which one parent worked a nonstandard shift. On this, she was inspired in part by her own family: a sibling who's a nurse, another a firefighter, both with children.

These are some of Leibbrand's findings:

- A mother's night shift tended to have benefits for boys and girls, especially when they're young

- A mother's rotating shift, or a split shift -- say, going to work for a few hours in the morning, and again in the evening -- was associated with greater problems among boys of all ages, and among older girls

- A father's rotating or split shift was associated with more behaviour problems among girls, particularly younger girls

- A father's night shift tended to coincide with behavioural benefits among boys

The gender differences may relate to parent involvement.

Some research finds that fathers tend to be more involved in their sons' lives, perhaps explaining why fathers' shift schedules are more likely to be associated with benefits for boys.

Other research on the impact of shift work on adults' physical and emotional stamina, Leibbrand said, suggests that parents who work nonstandard schedules may be under more stress and sometimes have less energy, or "psychological capital" to meet their child's needs.

Unstable shift schedules, like rotating shifts, could be especially stressful for parents.

This stress may have important repercussions for children, as children learn to model their parents' behaviour.

But when it comes to nonstandard shift work, a consistent schedule -- the same hours, on the same days each week -- appears to buffer the negative effects, according to Leibbrand's research.

It provides consistency in child care, gives children more structure and allows the family to predict a parent's availability for activities.

A parent who regularly works the night shift, for example, may deliberately try to be awake and available for children before and after school, while the other parent handles dinner and bedtime routines.

But families don't always have the resources for child care or control over work schedules. That's where employers and policymakers come in, Leibbrand said.

Solutions could involve allowing greater flexibility in the workplace or in providing paid family leave and access to quality child care.

"Most parents want to spend time with their children and want to find a way to do that," she said. "We should be prioritising people's well-being and balancing of work and home life."

The study has been published in the Journal of Family Issues.

Lead image used for representational purposes only.