'I can snap my fingers and get 1,000 people overnight, but I can't guarantee that they will develop because there has been zero change in education in the country in the last nine years.'

Nikita Puri and Dasarath Reddy report.

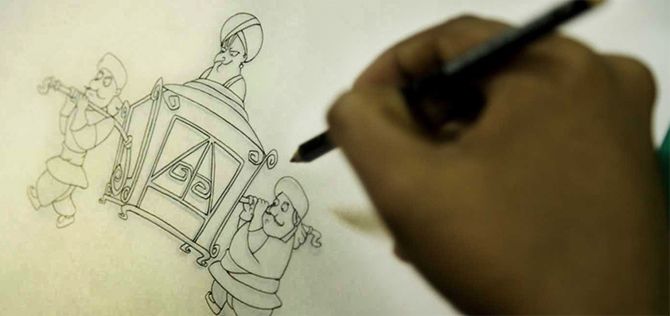

Seated at a round table, like King Arthur's knights, are students at Arena Animation in Malleshwaram, Bengaluru.

Armed with plain paper and pencils, they all have their own holy grails to pursue.

One of them is sketching a human figure frozen mid-flight.

All rippling muscles and wearing only underpants, a red lightning-shaped mask covers the character's face.

"I'm still deciding on his superpowers," says the student.

Behind the group is a table covered with clay Ganeshas -- the result of an anatomy class coinciding with a festival.

On another floor, a student has just finished making a dragon in 2D.

She had dreamed it up a while ago and now wants to see it in "real and 3D".

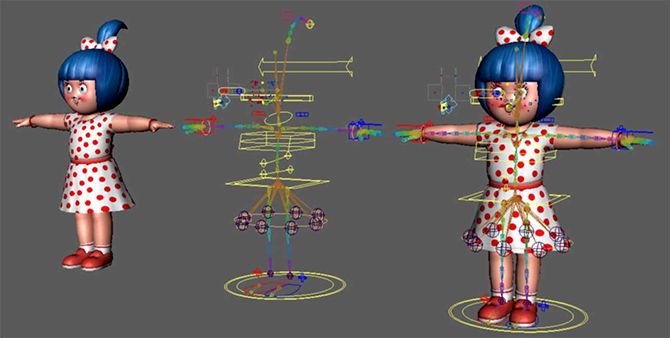

From scenes shot in the green room to another room where there's a session on how to build 3D skeletons (called rigging), India's animation story arises from places such as these.

It then takes on a life of its own as it enters studios, largely in Mumbai, Hyderabad, Bengaluru and Chennai.

According to a 2018 report by consultancy EY, the media and entertainment industry grew 13% to reach Rs 1.5 trillion last year.

This growth was led by digital media, film and animation and visual effects segments.

Analysts expect this sector to grow two-three times by 2020.

"The recent success of Incredibles 2, which collected over Rs 300 million, gave us the boost to bring Ukranian fantasy film, The Stolen Princess, to India and also dub it in Hindi, Tamil and Telugu," says Rajat Agrawal, syndication and creative head, Ultra Media & Entertainment group, Mumbai.

India-born animation for Indian audiences has for long been marked by shallow pockets and sub-par content.

But change is coming.

"Producers are increasingly going after scripts which merge good storylines with visual effects rather than banking on a single character," says Sudhir Reddy, head of Digital Domain's Hyderabad studio.

"They aren't cutting corners anymore. It's not happening on a large scale yet, but it is a good start."

The budgets of animation TV shows have doubled over the past 10 years, says Rajiv Chilaka, creator of the popular Chhota Bheem series, and founder, Hyderabad-based Green Gold Animation.

But, says Reddy, "Content for pre-school audiences, as well as exclusive content for girls, which is huge across the world, still remains to be explored in India."

A significant hurdle that studios collectively agree on is a lack of "industry-ready" talent.

There are more than 100 fine art colleges in Karnataka alone, but many of these artists haven't touched a digital tool, says Bengaluru-based Biren Ghose, country head at India for Technicolor.

"It took me four years to get 60 artists. I can snap my fingers and get 1,000 people overnight, but I can't guarantee that they will develop because there has been zero change in education in the country in the last nine years," laments Pete Draper, founder of Makuta, the company that created computer-generated imagery of the waterfalls in Baahubali, the movie series.

Two decades ago, though, people like Srinivas Sribhakta, director of Arena Animation's centres in Bengaluru's Malleshwaram and Rajajinagar, took the initiative in plugging the training gap.

This was the time when Hollywood was looking to outsource work.

When Sribhakta started his institutes, he remembers going door-to-door just to talk to parents about encouraging their children to study animation.

He describes that first generation of students as "risk-takers".

Today, Sribhakta is the secretary of ABAI (formerly the Association of Bangalore Animation Industry, the body uses just the acronym now).

The two centres he heads have 800 students.

In total, Arena Animation has over 100 centres in India and Bengaluru alone produces 1,000 to 1,500 students, he estimates.

There are plenty of other institutes churning out batches of potential animators, too.

"Besides availability of talent, it was also our knowledge of English that diverted projects from China and the Philippines to India," says Vaibhav Kumaresh of Mumbai-based Vaibhav Studios.

He is also a member of a Mumbai-based association of volunteers, The Animation Society of India (TASI).

Among Kumaresh's best-selling original characters is Lamput, a gooey orange shape-shifting creature.

The animation industry is broadly divided into two.

"One is where you provide services for ideas given to you from outside agencies. The other is where you create original content and seed ideas in the studio," explains Simi Nallaseth, an animator who worked on Ice Age (2002).

Projects such as Kung Fu Panda, Penguins of Madagascar and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles fall into the first category and good chunks of these films were made by Technicolor in India.

Finding a stuffed Mickey Mouse in a grown man's office can be a bit startling, but not if that man is Ghose of Technicolor, the production power house that has bagged seven Emmy awards in the past eight years.

Right above the Disney character is a framed image from The Jungle Book, which won the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects in 2017.

Ghose is also president of ABAI.

In India, where Pokémon and Shin Chan (both imports) dominate the world of animation, a character like Chhota Bheem has moved the needle a little, but it should have been a much bigger franchise, says Ghose.

Much like how Kaun Banega Crorepati disrupted the market of game shows, India's animation industry "is still waiting for that one swallow that'll make a summer," he says.

It is in this space that a company like Bengaluru's Graphic India has stepped in to build home-grown characters, heroes and stories.

While Baahubali: The Lost Legends, an animated series by Graphic India, is on Amazon Prime, their action-adventure-themed Astra Force features Amitabh Bachchan as a mythical hero.

India has been in a long-drawn-out start-up phase where animation is concerned, and we've received some of the biggest projects for purely financial reasons, say veterans.

Indian labour, across industries, is famously cheap. And the industry has received flak for far-from-ideal working conditions.

Like in any fledgling sector, the conditions are too diverse to offer a typical image.

At one end there are animators who reportedly work out of shanties in Mumbai's suburbs; on the other, Graphic India's office is a comfortable bungalow complete with two dogs as permanent residents.

And Technicolor India's 3,300 employees operate from a posh business park in the midst of software companies.

The industry is such that it can be a stressful workplace.

"You have to burn the midnight oil when the release date is near. Some people take it positively, some call it sweatshops," says Reddy.

As the government recognises animation's potential to rake in big money and also create jobs, veterans say the sector will be reformed.

Animation, under the audio-visual industry, was been identified by the Centre last February as being among the 12 champion sectors whose development will be closely looked at.

State governments are stepping up, too.

In 12 months, Draper's company, Makuta, will move into the Image Tower in Hyderabad, a private-public partnership built to give a boost to the animation, gaming and multimedia industry.

ABAI, in association with the government of Karnataka, unveiled a centre for excellence in Whitefield, Bengaluru. This centre will continue to be supported by the state for three years.

It will offer a finishing school with tech at par with international studios, including motion capture (body) suits, an incubator for start-ups, and a post-production facility open to animation studios.

Much like the West has created superheroes, or Japan, Korea and China have exported their anime, manga and manhwa to the world, India is ready to take on the mantle of a global exporter of creativity, feels Sharad Devarajan, co-founder and CEO, Graphic India.

"Our responsibility is to find young talent and give them the resources to take their ideas to the world."