Vat Vrikshya -- banyan tree in Sanskrit -- helps tribal women, with absolutely zero formal education, set up businesses.

"One day I thought to myself, what am I doing sitting in a cubicle and making an MNC richer!"

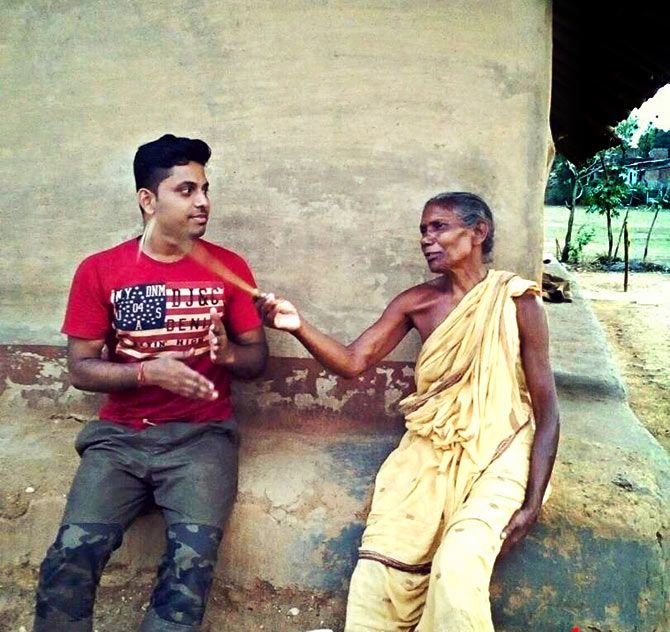

With these thoughts, Vikash Das, 28, decided to quit his high paying job as a security analyst at IBM, Bengaluru, where he had been working for three-and-a-half years.

"I had a good job, but I lacked engagement," he recalls. "I realised that professional success doesn't necessarily lead to happiness or fulfillment."

"I had a dream job, owned high-tech gadgets, lived in a fancy apartment and had luxuries that a 26 year old could possibly imagine. But I was not happy."

He needed do something more meaningful with his life.

A trip back home to Bhubaneswar decided what it would be.

Vikash decided to dedicate himself to the betterment of tribal communities in the Naxalite-infested areas of Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and West Bengal.

While hunting for ways and means to help this group of needy people, he realised his focus had to be on tribal women.

Vikash figured out the importance of supplementing the incomes of these women by guaranteeing they had an alternate occupation.

Thus began Vat Vrikshya, which he founded, that helps tribal women, with absolutely zero formal education, set up businesses.

Vat Vrikshya in Sanskrit means banyan tree -- his first meeting with the tribals was under a banyan tree, so he decided to go with that name.

Wondering how he does it?

First, an initial donation of Rs 2,000 from Vat Vrikshya, which he seeded, is made to women of every family in the villages where Vat Vrikshya works.

The women are welcome to add their savings to that amount and set up a small business.

Then, he trains them to create 'commercially viable products' using traditional handicraft skills like pottery, metalwork, pickles, saris, shawls, etc which they market in local bazaars or venture to big cities with.

If these women need help with marketing, Vikash steps in.

If they need to secure loans to run their businesses, he helps them.

Clueless about availing government subsidies or maintaining balance sheets, he takes care of that too.

If need be, these women are given vocational training as well.

The idea is simple: To provide as much help as possible to tribal women so that they can become self-sufficient entrepreneurs.

In the three years since he founded this social enterprise, Vikash has not only helped several tribals set up their business, but also augmented their income by 30 per cent.

A graduate in information science from the Visvesvaraya Technological University in Belgaum, Karnataka, Vikash completed his master's in software engineering from Manipal University, Manipal, also in Karnataka.

His father is a retired banker and mother, a homemaker.

"I am the first generation entrepreneur," he says.

"The Adivasis lost their land and livelihood. They were physically isolated from mainstream society and had no access to markets to sell their products. Tribal children were malnourished and had no access to education," he says.

All these factors pushed Vikash into working for tribals his mission.

"I had no concrete plans, but I was confident of making a difference in the life of these people. Today, I may not be earning as much as I used to, but I am happy and satisfied."

Rediff.com's Anita Aikara spoke to Vikash Das in Balasore, Odisha, where he is based, about his work, his dreams.

How did your family react to your decision?

It wasn't easy for them. They thought that I was putting my life at risk. Later, when my parents got to know my ideas, they supported me.

I was born and raised in a tribal predominant region. I got the chance to interact with several tribal villagers, in and around my town Balasore. I have witnessed how tribals are neglected and ill-treated.

As a child, I always wondered why God was so unfair to them. Gradually, I realised it's us who could really bring about a change.

I felt that charity and few hours of voluntary work every week could make a difference.

Tipping point?

Something happened (on a trip back) to my hometown that changed my notion forever.

I saw an old tribal woman, holding her grandson, begging outside a temple.

When she tried to enter the temple, she was literally abused and thrown out. They considered her impure and unclean.

After witnessing that, for the first time, I felt a deep sense of responsibility, being a part of the same society.

That set in motion a number of questions... Why am I here? What is my purpose on earth?

I am blessed to have access to opportunities that a lot of people might deserve, but don't get.

That's why I decided to start a sustainable social enterprise to create diversified livelihood opportunities for tribal women, rather than giving them charity.

I wanted to make them business partners, so that they could earn and live a dignified life.

The self-replenishing social good business could generate profits that are later utilised to tackle social problems in that region.

Foray into social good:

Every now and then, one can read in the newspapers about the plight of tribals.

Some of them work as bonded labour and are exploited...

A couple of years back, the fingers of two tribal migrant workers were chopped off because their (employer) felt their work was poor.

Tribal girls have often been victims of child trafficking.

The Dana Majhi case (a photograph of Majhi, a tribal, Kalahandi district farmer, carrying home his dead wife, on his shoulders, made international headlines) sheds light on the kind of social discrimination tribal people experience.

Such cases aren't acceptable, especially when our country is the emerging superpower.

My core purpose is to encourage the economic empowerment of women artisans through handicrafts, uplift their social status and strive for their education, health and financial security.

(Subsequently) adequate livelihood opportunities and favourable work conditions have helped women to stay at home instead of migrating to cities.

They are using their monthly earnings to invest in agriculture, get their children educated and to take care of their family's health.

We have developed a beautiful range of commercially viable products putting their traditional handicraft skills to good use.

This is like a school, where the women, with no formal education, are provided business skills and made financially literate.

How many women began with you at the outset?

Initially, we started with 22 tribal women.

The number has grown to 2,300.

Dhokra is very popular among the tribal people of Odisha, Chhattisgarh and West Bengal.

Did you live with the tribal people when you started out to understand how you might be able to help them?

Initially, it was like looking at the tribal problems from a glass wall.

So, I stayed in tribal pockets for two months.

It wasn't easy for someone like me, who was working in Bangalore and had a comfortable life.

There were no electricity, roads, Internet, mobile networks or a proper place to live.

Add to that the language barrier.

The tribal households are solely dependent on agriculture and forest products for their livelihood.

Because of adverse weather conditions and outdated agricultural techniques, their farming was not productive.

Poor Adivasi women had to walk for miles, in difficult conditions, collecting wood, gathering fodder, picking leaves, brewing liquor and selling (their products).

Very generically, the major problems are geographical isolation, unemployment, landless-ness, illiteracy, malnutrition, health problems, sanitation, non-profitable agriculture, exploitation by middlemen, traders and money lenders.

What are the kind of diverse livelihood opportunities you help the tribals with?

Vat Vrikshya provides training and building support capability to tribal women by promoting tribal handicrafts in cities.

We also give market linkage to tribal artisans and nurture entrepreneurial skills.

The tribes of this town earn their bread through primary occupations such as hunting, gathering and agriculture.

In agriculture, due to the uncertainty of weather conditions and lack of proper infrastructure, farmers live a destitute life and often end up committing suicide.

To overcome this issue, the organisation has formulated the idea of cultivation of different ranges of crops in one patch of land.

Hence, there could be an option at times, when one crop fails.

The women are engaged in preparing handicrafts, pickles and medicines from wild flowers, roots and leaves. They are involved in mushroom farming at home and offer vocational training.

Did you ever face resistance from the Maoist groups or the locals?

Yes, we did face resistance from locals, money lenders and middlemen.

There was a huge trust deficit among tribals.

They thought we are another group of people, who have come to their villages to exploit them.

Women weren't allowed by their family elders to interact with us and talk about their problems.

It was very difficult to click their pictures or even talk to them, as they required their husband's or son's permission to talk to us.

Due to lack of financial support, they were very vulnerable to loan sharks and money lenders.

Middlemen were exploiting tribal artisans by paying them a fraction of their wages.

The lack of information and effective market linkages were the main reasons for this poor eco-system.

When we put in efforts to fill these gap, we face resistance from money lenders and middlemen.

What were the other trials you faced?

The journey has been challenging as well as exciting.

To begin with, my family and friends were very upset that I was leaving my high paying job and settling down in a remote village.

They thought that something is wrong with me.

When they (understood) our business model and how effective it was, they gave in.

On the other end, since the tribals were always in the fear of being exploited by the outsiders, the toughest thing for us, during our initial stages, was to convince the community to become a part of this idea.

We operate out of of tribal areas, inaccessible to modern communication and transport.

Our team members risk their lives crossing dense forests and rivers to reach remote villages (Maoist infested areas) where outsiders may not be welcome for political or historical reasons...

Initially, they were sceptical about our idea.

When they gradually realised that the idea had the potential to change their lives they supported us.

It took its fair share of time to get them convinced.

Now the respect, the love and affection I get from them are heartening.

How did your presence help the tribals?

Now the women earn two to three times more than they were earning earlier.

So they have stopped (putting) their kids (to work, doing daily chores).

We encourage them to send their children to schools.

There are programmes for children which can help the dropout rates in school to be put under control.

Earlier, women lacked financial literacy and had poor-to-non-existent saving habits.

Women, who were earning some income from daily wages, or micro-scale enterprises, lacked the basic financial knowledge related to daily money management, profit and savings.

This led to increased dependence on private moneylenders which kept them trapped in the cycle of poverty.

Now the women not only manage the loan amount productively, but also help in an all-round development of society.

With growing confidence of being able to earn and save money, the women have now become important participants in decision-making processes.

Women now understand that if they don't save money in banks, the men would spend the earnings on alcohol.

Another important achievement is that women have stopped hiding their accounts, and openly admit that they earn and save, so that they can help when their families are in need.

Do you receive some remuneration as well?

No, we do not receive remuneration. We are a self-sustaining organisation.

We have our offices in Bhubaneswar and Balasore. There are 72 (of us).

A few are volunteers, the others are our shareholders (women artisans).

The profits that we get from the sale of the products is divided between the women artisans who are shareholders and me.

That's how we sustain ourselves.

Part of our profit also goes on training and other activities.

Part of it goes for the education of tribal kids and other social welfare activities in those tribal pockets.

Do you think the younger generation is hesitant to give back?

Is it because of the challenges. Or they are just lazy?

Almost each one of us wants to do our bit for society, but we tend to get sceptical.

We constantly ask ourselves, 'How does it matter if I contribute or not?' (They think) there are others, who can do good for society.

At times we ask ourselves, 'Do we have enough resources or the capacity to serve our interest of doing good for our society?'

I think the issue with our young generation is that they are always hesitant to take the first step of listening to their heart.

The moment they try to do so, the inner voice of self-doubt creeps in and gets louder.

The way forward

We plan on maximising product distribution.

Through effective digital commerce expansion, we could get the tribal handicrafts to markets across India and abroad.

We aspire to change the lives of 50,000 tribal families by 2030.

This will be achieved by empowering women artisans from each family.

We will also provide training to 35,000 rural women to start a new business.