Vaihayasi Pande Daniel discovers Ross Island where the clock can never be turned back.

There's a little speck of Indian territory -- smack in the middle of the Bay of Bengal -- that once, briefly, was in the eye of history.

You have probably never heard of this tiny smudge of land.

Its name is Ross.

When you journey to the Andaman islands not many people tell you to head to Ross island near Port Blair.

They suggest you visit the cellular jail, Port Blair, where hundreds of freedom fighters (including nearly my grandfather) were incarcerated by the British.

They say you must not miss going to the pristinely splendid Havelock Island, a place of sparkling beaches and iridescent coral waters.

Or to see the spot at South Point, Port Blair, where Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi hoisted a flag last year, that is now marked with the giant numerals 1943. The flag raising in 2018 was to honour Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose who raised the tricolour at the Gymkhana ground in Port Blair on December 30, 1943 declaring the islands the first independent Indian territory, which he named Azad Hind.

But plenty of history was made on the lonely, windswept Ross island too.

And the abandoned isle, which is about as big as Mumbai's Nariman Point and was called Paris of the East, has a haunting, melancholy beauty that is bewitching.

Ross is a place that stuns too because it is hard to visualise how so much history came to pass on such a remote, forlorn island, far away from the rest of the world.

Accessed only by water from the Aberdeen jetty at the Rajiv Gandhi water sports complex, Port Blair, Ross is about a kilometre away from the capital of this Union Territory by speed boat. The ride will set you back about Rs 350 per head.

As you approach the sun-dappled island your first sight is of swaying palms and the Tricolour.

It is only after you get off the craft, buy your ticket and wander in, that you see the splendid, ghostly ruins. Wandering amongst them wistfully floats you back to another period of history.

Ross Island, now renamed Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose island, was once on the crossroads of world history, during turbulent times, for a brief few decades. And how colourful those years were!

The earliest colonists of the Andaman and Nicobar islands were probably the Cholas, in the 11th century, who used the archipelago as the location of a naval base in their skirmishes against the rulers of Srivijaya empire (now Sumatra, Indonesia).

The first European colonists were the Danes in 1755 and they gave parts of the Nicobar islands the unlikely name of New Denmark and later Frederick's island. In 1778, in their footsteps, unknowingly, followed the Austrians, who called the parts of the archipelago they took over, Theresia islands.

But it was the British who finally staked a more lasting claim in this region, first on the Andaman islands in the 1780s, which extended to the Nicobar islands (after the Danes relinquished or actually sold their rights in 1868).

The islands were subsequently charted from 1788 in a meticulous manner by East India Company marine surveyor Archibald Blair.

After the Mutiny of 1857, the British decided to establish a much more permanent penal colony on the Middle Andaman island, ensuring, in a way, that the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago, luckily for us, became a part of British India, though geographically it was far closer to the then both British-ruled Myanmar and Malacca (modern-day Malaysia) or the Dutch-ruled Sumatra.

The British hit on wee Ross, named after another British marine surveyor Daniel Ross, as the location for the prison colony, because of a shortage of water at Port Blair.

Jailer Captain Dr James Patterson Walker, who arrived in 1858 with apparently 774 prisoners (mutineers) and an army of staff, was in charge of the operation.

Not only was the prison established on Ross, but the British also chose to live on the island, making this sultry Bay of Bengal locale their home and administrative quarters from 1858 to 1941.

To that end a rather elaborate seat of power was constructed on Ross. Basic barrack huts were put up for the prisoners and the prisoners were bullied into building the various ornate structures that came up on the island. The island gained importance and the superintendent of Ross was promoted to the rank of chief commissioner.

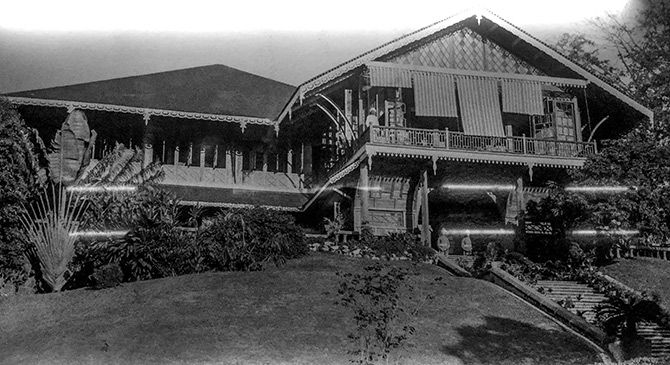

Just how extravagant life was on this remotely located, lonely island in those days is easily discernible from the ruins of the buildings left behind, that even today boast ballrooms, Italian tiles, spring-mounted dance floors, sweeping architecture and heavenly vistas.

When you examine the buildings -- the church, the government house etc -- one is mildly astonished at the vigour with which the British adapted to Ross Island and recreated a life -- quite like what it might have been like in say Cambridgeshire, England -- all the way across two oceans at this distant tropical jungle outpost.

The island, which is not even 2 km, across had two clubs (one of which was for the officers and the other was called Subordinates Club), bakeries, stables, a hospital, the governor general's mansion, a secretariat, a printing press, a church, water treatment plant, an artillery, a cemetery, a swimming pool, a hospital, tennis courts, its own newspaper (Ross Island Literary according to Wikipedia) and more.

All too many ghosts dance tantalisingly before your eyes as one strolls through the now wild Ross. You can imagine the squeak of swirling carriage wheels, the neighing of horses, the fancy balls and the rustling of silks and taffetas, the whoosh of punkahs, the smell of horse dung and ladies' perfume, the starch and chatter of Indian bearers.

You are conflicted. It is a moment when you feel the insistent and compulsive urge to voyage back in time to vicariously know or relive a grandiose epoch in history.

At the same time you are perfectly aware of the tendency of the mind to glamourise and romanticise the excesses of history.

It, weakly, does not have the ability to wrap itself around the terrible miseries that must have lived, side by side, on the island -- the wretched condition of the prisoners, who enabled this beautiful life, and the painful early deaths among the island residents -- be they the imprisoned or the imprisoning -- from malaria, dengue and other fierce tropical diseases that gave the dreaded Kala Paani its name.

The whole place has an overgrown Manderley (a la Rebecca) feel with the foliage and the peacocks gradually gaining the upper hand.

As you wander through the crumbling ruins you notice how the enormous peepul trees and banyans now firmly rule the roost. Their ever-advancing roots and branches are actually the rapacious tentacles of Nature, a serene half smile on her face, taking back the island, righting historical wrongs in her own judicious and faintly sardonic manner, relegating Ross to oblivion.

Ironic too was what happened to the island.

When the Japanese invaded Andaman and Nicobar in 1942, the British fled, but not before a deputy chief commissioner was beheaded and other top administrative figures were imprisoned and later sent as prisoners of war to Singapore.

The Japanese, as the new conquerors, fancying themselves to be nose-in-the-air toffs too, took up residence in the elegant buildings left behind by the British, with the Japanese admiral occupying the chief commissioner's mansion. They built a few bunkers to protect their conquest.

A famous visitor to the island was Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose who spent a day on Ross in December 1943 meeting Japanese officials and hoisting the Indian flag on Ross's government house.

By 1945 Ross's time in the limelight was over.

The Allied forces overpowered the Japanese and took the Andaman and Nicobar islands back. Ross was eventually deserted.

Never again would the microscopic island regain its grandeur or find another moment to call its own in history.

As you exit the island the ghosts call out to you wondering if you too will ever be back.

One of the epitaphs from the cemetery says it all, for Ross too:

He glanced into our world to see a sample of our misery

Then turned away his languid eye, to drop a tear or two.

And die.