‘Is this man crazy?’ the postmaster asked.

‘Yes, who? Ali, na? Yes, saheb. Five years have passed and, no matter the weather, he comes to collect a letter. It’s very rare for him to receive a letter,’ the clerk replied.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

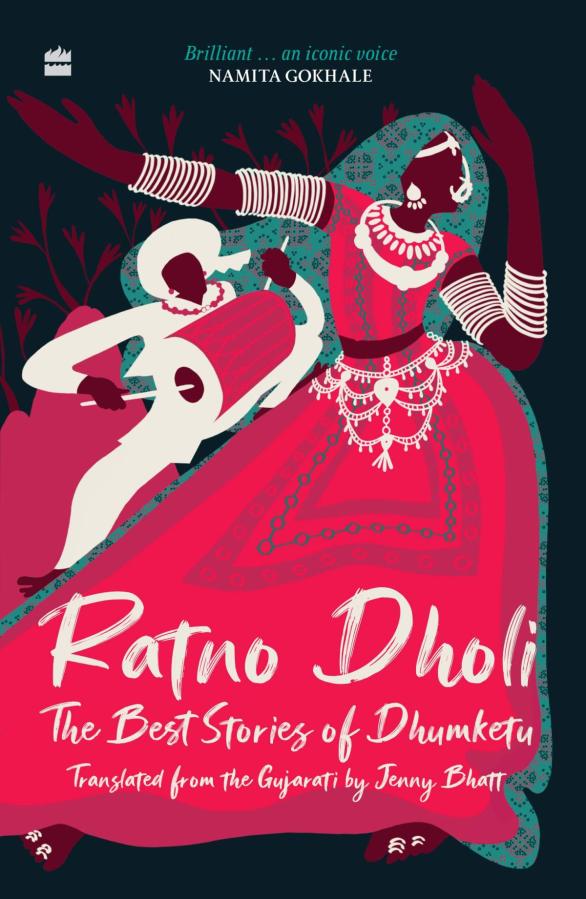

Dhumketu was the pen name of Gaurishankar Govardhanram Joshi, one of the foremost writers in Gujarati and a pioneer of the short story form.

When his first collection of short stories, Tankha, came out in 1926, it revolutionised the genre in India.

Characterised by a fine sensitivity, deep humanism, perceptive observation and an intimate knowledge of both rural and urban life, his fiction has provided entertainment and edification to generations of Gujarati readers and speakers.

Read on to enjoy one his most well-known short stories, The Post Office.

The hazy dawn sky was glittering with the previous night’s stars -- big and small -- like happy memories shimmering in a person’s life.

Wrapping his old, tattered shirt tighter around his body to protect against the blasting wind, an old man was making his way through the centre of the city.

At this time, the unrestrained, rhythmic sounds of mills grinding, along with the delicate voices of women, could be heard from many homes.

The odd dog’s bark, some early riser’s footsteps heard from a distance, or some prematurely awakened bird’s tone -- except for these, the city was entirely silent.

People were snoring in sweet slumber and the night was more dense thanks to the cold of winter.

Bearing the pleasing temperament of a man who can kill without uttering a word, the cold was spreading its tentacles all over, like a deadly weapon.

Shivering and tottering quietly, the old man exited the city’s gates to reach a straight path and, slowly-slowly, continued walking with the support of his old stick.

On one side of the street was a row of trees, while the city gardens stood on the other.

Here, it was more chilly and the night was more velvety.

The wind pierced right through and the fine brilliance of the morning star, Venus, fell on earth like an icy flake of falling snow.

At the very end, near the edge of the gardens, there was a beautiful building. And lamplight was spilling from its closed windows and door.

As a devout person experiences a reverential joy on catching a glimpse of the destination of his pilgrimage, so did this old man feel happy upon spotting the wooden arch of the building.

The arch had the words ‘Post Office’ painted on an ancient signboard.

The old man sat outside, on the verandah.

There was no discernible sound from inside but he could hear some indistinct whispering, as if some people were busy at work.

‘Police superintendent!’ A voice called from inside.

The old man startled, but sat back down quietly again. Faith and affection were, in such cold weather, giving him warmth.

The noises inside began to rise in intensity.

The clerk was reading out the English names on letters and tossing them towards the postman. Commissioner, superintendent, diwan saheb, librarian -- calling out such names one after the other in a practised manner, the clerk was flinging the letters rapidly.

During that time, a playful voice called from inside: ‘Old coachman Ali!’

The old man sat up where he was, looked up at the sky fervently, moved forward, and placed a hand on the door.

‘Gokalbhai!’

‘Who is it?’

‘You said old Coachman Ali’s letter, right? I’m here!’

In response, there was merciless laughter. ‘Saheb! This is a crazy old man. Does a futile round of the post office to collect his letter every day.’

As the clerk said this to the postmaster, the old man sat back in his place. Over the past five years, he’d developed a habit of sitting in that spot.

Ali had been a skilled hunter. And, slowly-slowly, he had become so proficient that, like the addict needs opium, Ali needed to hunt.

As soon as his eye spotted the colourful partridge, which could somehow still blend like dust within dust, it would be within his hands!

His sharp scrutiny could reach into a rabbit’s warren.

Sometimes even the hunting dogs couldn’t separate the dirty grey colouring of a clever rabbit sitting hidden with cocked ears in the nearby dry, yellow kaasda or raampda grasses.

The dogs would carry on forward and the rabbit would be saved.

But Ali’s sight, like that of an Italian eagle, would land precisely on the rabbit’s ears and, in the next moment, it would be no more.

Then, sometimes, Ali would team up with the fisherman to hunt in the water.

But when the twilight of life seemed to be approaching, the hunter abruptly turned in another direction.

His only daughter, Mariam, got married and left for her in-laws’ home. Her husband worked in the army, so she went to Punjab with him.

From that Mariam -- for whom he had been holding on to life -- there had been no news for the past five years.

Now Ali had learnt what affection and separation meant.

Earlier, one of the pleasures of the hunt was the baby partridges running around in bewilderment once he had shot and killed the parent. The delight of hunting had permeated every nerve.

But, since the day Mariam left and loneliness engulfed him, Ali had forgotten the hunt and begun staring steadfastly at the brilliant green fields teeming with grain. And, for the first time in life, he understood that a universe of love and tears of separation, both exist in nature.

One day, Ali sat under a palash tree and cried his heart out.

From that time on, he would awake at 4 am every morning to arrive at the post office.

There was never a letter for him but, with fervent devotion and hope-filled cheer that his daughter’s letter would arrive one day, he always showed up before anyone else and sat waiting outside the post office.

The post office -- perhaps the most uninteresting building in the world -- became his holy land and place of pilgrimage.

He always sat in the same spot, in the same corner.

Upon seeing him, everyone would laugh. The postmen would make jokes and sometimes, in jest, call out his name even though there was no letter, making him come running to the door of the post office in vain.

As if possessing an endless faith and resolve, he came every day and returned empty-handed.

While he sat, peons came one after another to pick up their office documents.

Largely, these twentieth-century peons were like the secret confidantes of their officers’ wives. So the private history of every officer in the entire city was recited now.

Someone sported a turban. Another one had sparkling boots on his feet. In this manner, each one displayed his unique status.

Just then, the door opened and, in the lamplight, the postmaster sat in the front-facing chair with his pumpkin-like head and displeasure-filled, indifferent face.

With no radiance on the forehead or face or eyes, the clerk and postmaster of this century are rather like Goldsmith’s village schoolmaster.

Ali did not shift from his spot.

‘Police commissioner!’ the clerk boomed and a young man reached his hand out impatiently for the police commissioner’s letters.

‘Superintendent!’

Another peon came forward.

And, in this manner, the clerk always read out the entire list for names like a Vishnu devotee.

Eventually, they all left.

Ali got up. As if there had been some miracle in the post office, he offered his salutations to them and left. Arrey! Like some villager from ancient times!

‘Is this man crazy?’ the postmaster asked.

‘Yes, who? Ali, na? Yes, saheb. Five years have passed and, no matter the weather, he comes to collect a letter. It’s very rare for him to receive a letter,’ the clerk replied.

‘Who’s sitting with free time? How can there be a letter every time?’

‘Arrey, saheb! But his mind has slipped away. Before this, he committed many sins. And then he did some wrong in some place. Bhai, one must suffer for one’s actions.’ The postman offered support.

‘The crazy ones are very strange.’

‘Yes, I had once seen a madman in Ahmedabad. He made piles of dirt all day. Bas, nothing else. Another one had a habit of going to the riverbank every evening and pouring water on a stone.’

‘Arrey, I know of one who walked back and forth all day. Another kept singing a poem. Yet another kept slapping his own cheek. And then, believing that someone else was hitting him, he would keep crying.’

Today, the mythology of the mad had emerged in the post office.

Taking examples like this and talking about them for a few minutes at leisure has become an established habit for pretty much every working person -- much like an alcohol habit.

Finally, the postmaster got up and, while leaving, commented, laughing: ‘Gosh, the mad folks also have their own world. The crazy must consider us crazy and their universe must seem like a poet’s universe.’

One of the clerks would, when time allowed, enact some behaviours of madmen.

Speaking these last words in the direction of the clerk who often caricatured the actions of madmen, the postmaster went away laughing.

The post office became as quiet as before.

Part 2: : The Post Office

Excerpted from Ratno Dholi: The Best Stories Of Dhumketu by Jenny Bhatt , with the kind permission of the publishers, HarperCollins India.