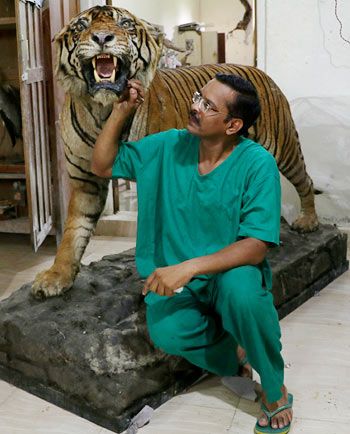

Mumbai's Santosh Gaikwad is on a mission to preserve India's wildlife for future generations, says Nikita Puri.

Photographs: Hitesh Harisinghani/Rediff.com

Two years ago, minutes before a flight to Mumbai took off from Delhi, the airline crew announced that a 'Dr Santosh Gaikwad' was required to approach them immediately.

"I instantly knew it was about my bags," says Dr Gaikwad, 42.

In a hurry to catch his flight after a long trip from Nainital, Dr Gaikwad had checked in two bags.

"There was a security alert because scans showed that one of the bags had a skull with canines and big bones. I had all the required documents, but I hadn't shown those papers in my rush to board the flight," says Dr Gaikwad, laughing.

The other bag contained a tiger skin.

Travelling with such oddities and handling the attention that is but a natural progression of carrying animal skin and bones is something that Dr Gaikwad has now become accustomed to.

A veterinarian by profession, Dr Gaikwad is the go-to guy for forest departments across the country as India's only practising taxidermist.

The skin and skeletal remains in his bag belonged to the country's last Siberian tiger, Kunal, who had died at Nainital zoo at the age of 22.

Dr Gaikwad had been asked to ensure that visitors to the zoo could still see a preserved version of Kunal for years to come.

He had heard that Siberian tigers were the largest in the family of big cats, but he had to compare Kunal's femur (thigh bone) with a lion's to confirm the fact.

Dr Gaikwad realised he wanted to be a taxidermist when in 2013 he saw the animal trophies at Mumbai's Prince of Wales Museum of Western India (now called the Chhattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya).

"The point of taxidermy is to preserve the past for future generations," says Dr Gaikwad. "I was always aware that a number of birds and animals in India are vanishing and we needed to preserve them."

His sentences are infused with a sprinkling of "baba" and "barabar hai na", marks of someone who has always called Mumbai home.

When he started out as a budding taxidermist, Dr Gaikwad worked as an assistant professor teaching anatomy at the Bombay Veterinary College; he was a practising veterinarian too.

A yoga and horse-back riding enthusiast, his fridge at home had tightly wrapped packages of pigeons, quail, ducks and chicken.

The thought that the birds might somehow contaminate the 'regular' food in the fridge concerned his wife, but he always assured her these were in well-sealed, air-tight bags.

"These domestic birds were my very first projects. I've spent more time on my dining table stuffing birds than I've spent eating," says Dr Gaikwad, who then quickly graduated to fish varieties like rohu, katla and mrigal before proceeding to cats and dogs.

Since he worked at a veterinary college, access to 'test subjects' was easy.

It was only after he had started out that Dr Gaikwad learnt the name of his new-found passion. " 'Taxi' means 'moment' and 'dermy' refers to 'skin.' It's about seizing the skin, like you seize a taxi, at the right moment," he explains.

The next thing he learnt was that there was no one who in the country who could teach him the art, nor were there any colleges teaching it.

Taxidermy, explains Dr Gaikwad, is a multi-disciplinary art and is the synthesis of five disciplines: Cobbling, sculpting, carpentry, painting and anatomy.

One has to be extremely patient, he explains. "A little extra force and the animal's skin can tear and become unpreservable."

After digging into reference books, Dr Gaikwad reached out to cobblers who taught him how to tan a hide.

Besides visiting design schools to see how sculptures were made, his education in taxidermy also came from the craftspeople who make idols for Ganpati puja.

By 2005, Dr Gaikwad was ready to wrap up his veterinary practice. Initially, the Maharashtra forest department was concerned about the continuity of taxidermy projects, if undertaken.

Besides, India's Wildlife Protection Act 1972 outlawed the hunting of wild animals and taxidermy trophies and now no one really knew how taxidermy worked. They hopped on board when Dr Gaikward painted the bigger picture, of preserving wild animals and birds for decades after their death.

Next, they needed to find a place with adequate workspace, light and water to set up what would become India's sole taxidermy centre.

Dr Gaikwad found a garage that fit in three minibuses and the Taxidermy Centre at Sanjay Gandhi National Park was officially opened in 2009. It's no longer unusual to find a lion, a sunbird, a python or even an ostrich in Dr Gaikwad's freezer.

Over the years, Dr Gaikwad has preserved a variety of animals: 12 big cats; a horse for the army; Himalayan black bears; a 140-year-old turtle which, at 6.3 feet, weighed 250 kg; a nine-feet alligator and over 400 birds, including a flamingo, peacock and the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard.

Some time ago, when forest officials in Gadchiroli's Alapalli jungles realised that a pachyderm stuck in flood waters wouldn't make it, they sent for Gaikward.

"I wanted to preserve the whole elephant; that would have been remarkable. But I was only allowed the head and trunk," he says.

That too came with its fair share of trouble. Since the head was heavy, Dr Gaikwad roped in two cobblers to help him with the work. "But when they saw the elephant, they wanted to immediately leave," he says.

His passion, in Dr Gaikwad's words, is ensuring "life after death."

So, pet owners are also turning to him. The most common pets brought in to be preserved include macaws and dogs.

When Mumbai-based Susmita Mallik's beloved Bruno passed away, the family couldn't say goodbye to the three-year-old German Shepherd. "It was not his time to go. Bruno wasn't a pet, he was a member of our family," says Mallik.

Two years after his death, Bruno continues to be a part of the Mallik family. "We asked Gaikwad to pose him in a seated position, he's done such a good job that Bruno looks as alert as ever," she says.

Stuffing exotic birds can cost Rs 3,000 while, for dogs, the price is Rs 10,000 to Rs 18,000, depending on the size and kind.

Dr Gaikwad's children, Samruddhi (14) and Sarthak (9), regularly take news clippings about their father to show their friends. "They feel very proud when I'm called to the school to talk about taxidermy," he says.

Archana Khamkar, a Mumbai-based schoolteacher who has been attending his workshops, says it is difficult to get people to leave after the sessions.

At one of the workshops, when a young boy approached Dr Gaikwad and asked if they could stuff his friend's dog when he passes away, Dr Gaikwad proceeded to tell the child how to preserve the body for taxidermy.

"The dedication he brings to the table is unbeatable," says Khamkar, recollecting the time Dr Gaikwad spent in "perfecting" the position of a bird's eye.

"I hope to learn the art from him. There's no one else who can teach this."

While Dr Gaikwad accepts that this "isn't really for everyone," he worries that the practice shouldn't die with him.

"I had given birds at a workshop organised for wildlife authorities, but not one of them came back. Everyone is always curious about how it's done, but no one has taken it up," he says.

Dr Gaikwad says he will continue sharing the technique nevertheless and turns his attention back to work.

A loggerhead sea turtle (endangered category) and a two-feet porcupine are next in line to be preserved.