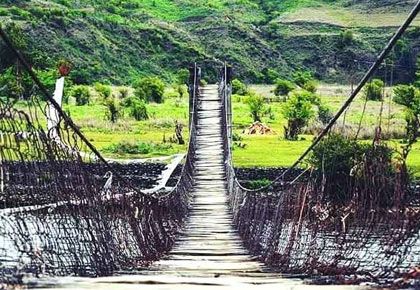

The Siang is a dramatic river that flows through a beautiful land.

Rafting on it is a rare pleasure the state offers tourists, says Ajai Shukla.

Most journalists encounter moments in their working lives when they pause, shake their heads and ask themselves: 'Am I actually being paid to cover this story?'

One such moment came in May 2003, when a television channel asked me to make the insanely beautiful, nine-day trek to the Mount Everest base camp in Nepal for the commemoration of Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary's first ascent of the mountain, 50 years earlier.

I would have paid to make that trip.

I felt the same last month when the Arunachal Pradesh tourism department invited me for the Siang Rush -- a three-day rafting trip down the swirling rapids of the grey-green Siang river, which enters Arunachal from Tibet, and flows for almost 300 kilometres through the state to Assam.

There, merging with the Lohit and Dibang rivers, it forms the Brahmaputra.

Dubbed the 'Mount Everest of rivers', this dramatic, 3,850-km-long watercourse has its source on the slopes of Mount Kailash as the Yarlung Tsangpo (Yalu Zangbu in Chinese), close to where the Indus, Sutlej and Ganga also originate.

After flowing placidly for over 1,000 kilometres across the high Tibetan plateau, the Tsangpo enters the eastern Himalayas spectacularly.

Foaming and churning like a furious beast, it thunders through the world's deepest gorge at the Great Bend -- a dizzying 16,000-feet chasm between the 25,531-feet-high Namcha Barwa and the 23,930-feet-high Gyalha Peri -- and then turns south into India.

The so-called Grand Canyon of the Tsangpo is thrice as deep as the Grand Canyon in Colorado, USA.

It is just as well that our expedition of mainly amateur rafters was not boating this stretch. No human has ever managed to do so.

In November 1998, four expert kayakers attempted the Great Bend, but called it off after one of them drowned.

In 2002, seven of the world's most experienced kayakers attempted it in February, when water flows are the lowest.

After almost losing their leader to a whirlpool, they were forced to carry their kayaks rather than paddle in them.

In contrast to these intrepid adventurers, the Siang Rush brought together some ten guests -- travel writers, photographers and Arunachal hands -- some of whom were white water rafting for the first time.

I had taken permission to bring my family along too, so my timorous, non-swimming, wife Sonia and worryingly gung-ho daughter, 10-year-old Meera, were in the boats too.

Also with us was Andy Leeman, a 64-year-old adventurer who has sailed many of the world's great rivers from source to sea -- including the Zambezi, Amazon-Orinoco, Mekong, Yukon, Ganges and Gomti -- in his storied 60,000-km river-running career.

In 2010, he had attempted the Brahmaputra, sailing from Mount Kailash to about 200 kilometres before the Great Bend, where soldiers of the People's Liberation Army abruptly terminated his expedition, telling him that foreigners were forbidden beyond that point.

So Andy came to Assam, bought new boats and resumed his Brahmaputra journey, sailing down to Bangladesh where the river meets the sea.

Now, armed with the Inner Line Permits needed for non-Arunachalis to enter the state and accompanied by his trusted cinematographer Apal Singh, Andy was embarking upon the third leg of his Brahmaputra journey.

We flew in to Dibrugarh, a charming tea town in Upper Assam, and boarded the ferry at the village of Bogibeel to cross the Brahmaputra.

We stayed the night in Pasighat, Arunachal Pradesh's oldest town, which the British established in 1911 to keep an eye on the untamed wilds of what was then called the North East Frontier Agency.

Over a drink (okay, several!), we met our host, Oken Tayeng of Abor Country Travel & Expeditions, who the Arunachal government had chosen to organise this showpiece event.

Tayeng engages in the most intriguing projects, such as locating and recovering the remains of US air force pilots whose aircraft crashed in the Eastern Himalayas during World War II, while ferrying supplies from airfields in Assam to Chiang Kai-shek's armies, who were fighting the Japanese in Yunnan and Szechuan.

The next day was spent in a six-hour drive up the Siang valley to Geku camp, where the rafting was to start.

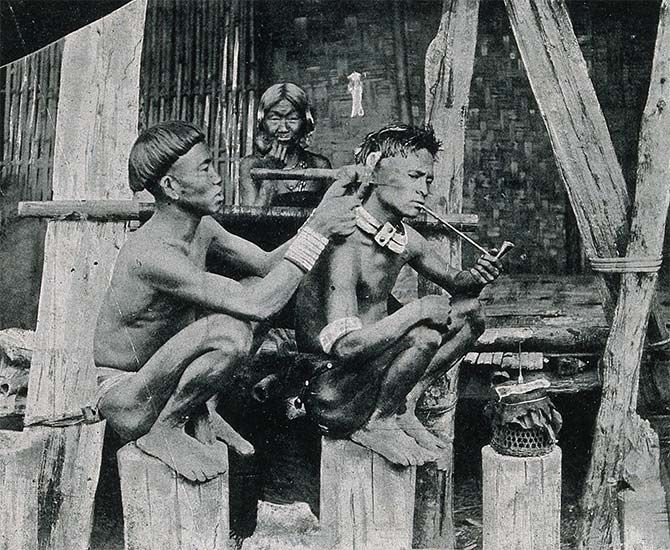

Tayeng had organised a delicious lunch en route, through a self-help group of Adi tribal women.

We wolfed down the chicken and fish, marinated and broiled in local tradition and served with rice on large leaves.

Due justice was also done to the local rice liquor, Apong, attractively served in glasses fashioned from hollow bamboo.

We reached our camp to find our tents pitched just yards from the river. Andy informed us that, on the Zambezi or Nile, we would have all been crocodile food by dawn.

While Meera chanted "Crocodiles, crocodiles, we want crocodiles" I crept off and surreptitiously confirmed that the Siang's croc population was zero.

We awoke the next morning in a quiver of anticipation. Peering out of our tents, we saw a blanket of fog over the Siang getting dissipated by the morning sun.

A quick camp breakfast -- boiled eggs, bread and jam, puri-alu -- and we assembled at the riverside to kit ourselves out.

Lined up alongside the rafts, the safety crew briefed us on what to do if disaster struck -- if someone fell out of the boat while navigating a rapid or, worse, if a boat overturned, trapping its crew underneath.

Our guardian angels would be four accomplished kayakers, brought in from Rishikesh, since kayaking is still new to Arunachal.

Calling themselves the Ganga Boys, they sported ponytails, designer stubble and wraparound shades.

But, once afloat, we quickly discovered how deadly serious they were about their work, which was to pull us out of the water within seconds of a crisis.

Once on the river, our apprehensions quickly dissolved; we were rafting a stretch that held only medium difficulty and danger.

Rapids are graded on scale of I to VI, with Class I representing a calm, smooth river and Classes V and VI indicating extremely dangerous rapids with difficult rescue conditions.

In the Class III stretches we were navigating, we could expect high, irregular waves and narrow passages that required precise maneuvering.

Moreover, the Class III rapids we ran -- with names like 65 Rapids, Begging Rollercoaster, Rottung and Big Pongging rapids -- were interspersed with long stretches of placid water that allowed us to practise rowing, ride pillion on the safety kayaks and even swim in the river.

Over the three days of rafting, even the most apprehensive of us (no names!) stopped screaming through the rapids, and the ones that initially vowed not to venture into the challenging Big Pongging rapids eventually did so with aplomb.

Meera insisted on swimming in the Siang in between rapids and, such is the pressure a child can create, that several avowed non-swimmers put aside their fears and tested the waters.

With days of rafting boosting appetites and fatigue, everyone enjoyed the three overnight camps.

Three Arunachali travel firms had established a camp each, one of them inaccessible by road. That camp, while basic, turned out to be the best, since a village had been co-opted to feed us and stage an entertainment programme.

After a community lunch, the village elders invited us to tour the hamlet where every door was left open for us.

The Arunachal government's eagerness to boost tourism was made clear by Pema Khandu, the state's 38-year-old chief minister who flew down from Itanagar for the closing party in Pasighat.

Khandu, accompanied by senior officials, listened carefully as we recounted our experiences.

Then the evening devolved into an Apong-soaked celebration, with everyone dancing to a local rock band.

Khandu himself took the microphone and belted out a vigorous rendition of Country Roads.

The official who was dutifully noting down suggestions about tourism development turned out to be an acid rocker with a particular enthusiasm for Pink Floyd.

That is what makes every visitor's memories of Arunachal Pradesh special: The recall of time spent with free-spirited people who are unapologetic about having fun and who ensure that visitors to their magical, green, paradise do so too.