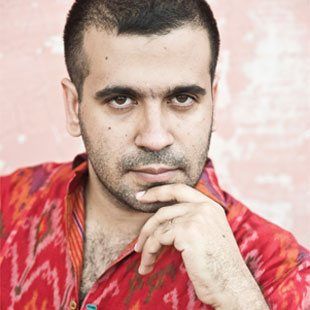

Textile designer Ashdeen Lilaowala does not see the Parsi gara as a relic of the past.

He uses the age-old technique on contemporary silhouettes as well as traditional saris.

This is what makes his work with the gara so important.

Lilaowala tells Abhishek Mande Bhot/Rediff.com why he is drawn to the technique and how it must change with times.

The gara, originally a heavily embroidered sari from China brought back by Parsi traders for their womenfolk in the 19th and early 20th centuries, is a highly valued heirloom in Parsi families. Some go back 100 years, when the China trade flourished.

Over time, the gara ceased to be much in use. But in more recent times, there has been a revival of interest in this beautiful textile.

As the community's numbers dwindle, textile designer Ashdeen Lilaowala isn't just attempting to keep the traditional gara technique alive, he is also making it more accessible to the younger generation.

Tell us about your work with the gara.

When I was studying at NID (National Institute of Design), I did a project for the Parzor Foundation (A UNESCO project for the preservation of the Parsi heritage).

When I was studying at NID (National Institute of Design), I did a project for the Parzor Foundation (A UNESCO project for the preservation of the Parsi heritage).

This was regarding kusti (the sacred thread worn by Parsis) weaving, which is now being published as a book titled Threads of Continuity.

As part of the project, I began researching gara embroidery.

After I graduated, Parzor got two projects from the Ministry of Textiles and Handlooms. One was for the development and promotion of the craft and the other was for documenting the craft.

For the first, we conducted workshops in Ahmedabad, Mumbai, Navsari and Delhi.

As part of the craft documentation process (that started around 2001), we looked at personal gara collections across India as well as in countries such as Iran and Hong Kong.

The idea was to trace the roots and routes of the tradition.

Later, when I was working at an embroidery studio in Los Angeles, I created a gara sari for a friend.

People were impressed and I offered to take more orders.

In 2012, I realised I had to formalise this process. So I started my label.

The idea was to create a new aesthetic using the gara technique rather than replicating it the traditional way.

I had to change proportions, work on the motifs, but at the same time keep the soul of the technique unchanged, so that when someone looked at it, they could immediately identify it as gara embroidery.

What attracted you to the gara particularly?

What attracted you to the gara particularly?

I was born in a Parsi family so it was part of my growing up.

My mother owns a few gara saris and she has a good eye for spotting a sari.

As a child, at weddings we would try to spot the hand-woven from the machine-made gara.

When I took up textile designing at the National Institute of Design, it seemed like a natural progression to pursue a project involving the cultural traditions of the community.

Tell us a little about gara embroidery.

The Opium Wars made it difficult for the British to deal directly with China.

So they found other ways to do business with them.

That is when the Parsi merchants stepped in and began to trade with the Chinese and picked cotton and opium as part of a tripartite arrangement.

This was also the time when the community began to prosper.

The gara saris are a product of this time.

While the European merchants would use the embroidered textile from China for screens and shawls, the Indian men thought they might make for wonderful saris.

The Chinese, never having seen a sari, had no idea how their cloth would be draped.

So the first few saris that came in were just yardage; they were embroidered edge to edge and had no border.

It was only when the women started travelling overseas that the element of a border, which framed the face, was introduced and specific details like leaving the corner of the pallu empty, as it would be tucked in, came in.

When the womenfolk got involved, the craft also took on a new aesthetic.

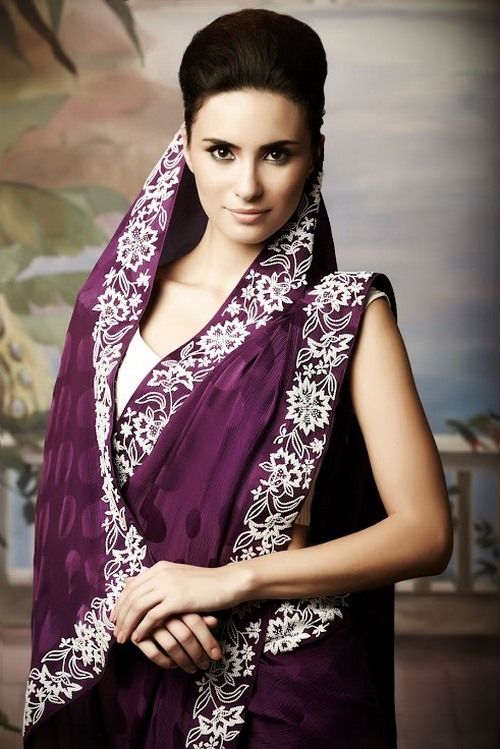

Colours such as purples, reds and blacks were introduced and the embroidery itself became the amalgamation of four cultures: Persian, Gujarati, Chinese and European.

As the trade prospered, so did the art form and in the early 20th century, it was at its peak.

However, in the years that followed, with the Independence movement and the importance placed on khadi and all things Indian, the gara began to lose its sheen.

It was only in the late 1970s and early '80s that (Mumbai-based) Naju Daver pioneered the revival of the art form and it has since made a comeback.

Today, a lot of gara embroidery is being done in Bengal.

What inspires your designs?

I am often inspired by Chinese and Japanese motifs.

Over the years, the crane motif has become associated with my brand.

But these days a lot of creative decisions are also driven by commercial factors.

Of course, one does follow one's instinct but one cannot do so blindly. Market demands have to be kept in mind while designing.

How has your design sensibilities changed because of this?

I am currently on a learning curve myself.

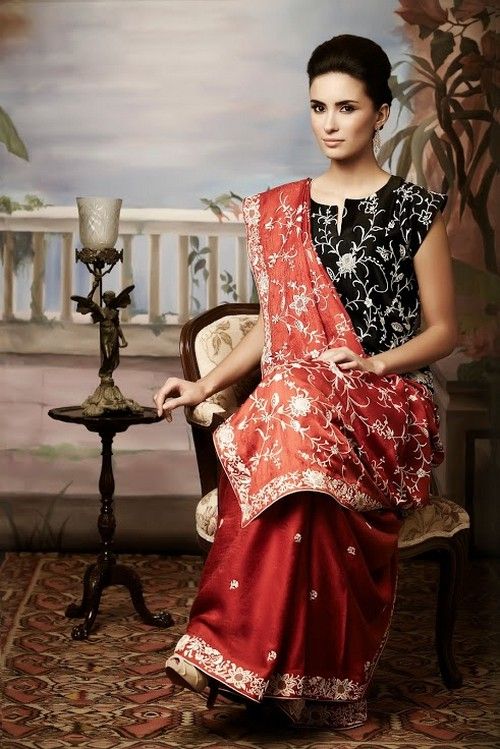

Over the years there have been a few broad learnings: Yellow simply doesn't work. Red is uniformly safe; you cannot go wrong with red.

People love black but several of them refuse to buy a sari of that colour because they cannot wear it at weddings and on auspicious occasions.

I interact with my clients; the more you interact with them the better you understand their needs.

Some women want more embroidery around the bust; some women prefer almost no embroidery except on the border.

Some women want more embroidery around the bust; some women prefer almost no embroidery except on the border.

Some women want a lot of drama, others prefer to be understated.

Teal green never works in Delhi. Chennai women are not comfortable with crepe and georgettes.

The Marwaris I dealt with only wanted kurtas with Parsi embroidery; they didn't want saris.

So the challenge really is to be able to find that balance and cater to the market without diluting your identity.

You don't have a store; how do you reach your customers?

If they are based in Delhi, I invite them to my studio there.

But I have been reaching out to them across various platforms over the years.

I started out by showing at exhibitions but I soon realised that it wasn't working for my business.

A typical customer comes to my store with the express purpose of buying something from me.

So I started doing trunk shows in association with stores across the country.

These are short, focused events during which we invite people to sample the designs, interact with them, take their feedback, and pack up and leave.

I don't send my designs to stores and let them sit; when my designs are there, I am there with them, taking notes and customising.

Typically, it takes minimum eight weeks for us to deliver the order.

How important are fashion weeks and celebrity spottings?

You can never quantify these things.

Of course it helps when a celebrity wears one of my designs – Sonam Kapoor wore one in her latest film Dolly Ki Doli -- because you get written about and you get enquiries.

Fashion weeks also give you a great deal of publicity. But at some point you have to take a call on what is important to you -- the fame or the fortune.

I don't mind giving out my designs to, let's say, Vidya Balan or Rekha or Hema Malini, who, incidentally, has bought a sari from me.

But I am not sure I would give it to a celebrity who wouldn't be bothered to wear it again.

You have shown at Lakme Fashion Week twice. What is your experience?

The first show was very well-received but I think I goofed in the second show because I was trying to put together a line that had a bit of everything.

Instead of following my gut feeling and simply designing 16 or 18 saris, I tried to make gowns and tops and pieces that I wasn't happy with.

The big learning there was to never ignore my instinct.

How do you plan to expand your business?

One way to approach it is to keep your business niche like (the Delhi-based designer) Vivek Narang, who has never shown at a fashion week, does not have a store but is on the radar of every well-heeled woman in Delhi and probably makes as much as, let's say, a TarunTahiliani.

The other approach is to go the whole hog, do the fashion week circuit, hire a PR firm, ensure you are featured in fashion magazines etc.

It is easy to fall into the fashion week trap and the whole business of being featured in magazines, but I find that it is important to expand steadily.

Rather than opening a store, I would travel city to city, slowly expand to (smaller cities) like Jaipur as also look at possible partnerships in overseas markets like Singapore, the UK and the US.

But right now, I am setting up the infrastructure to be able to deliver larger orders.

There is nothing worse than not being able to meet your deadline or delivering a shoddy garment.

Photographs courtesy: Ashdeen Lilaowala