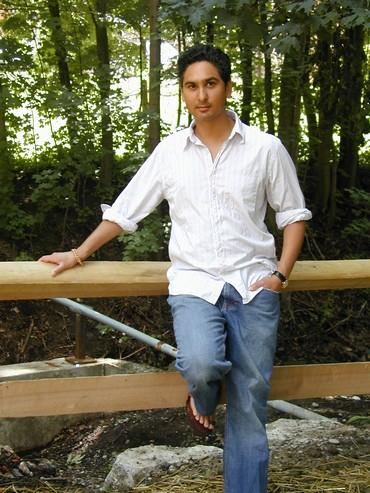

Debutante author Rahul Mehta tells Abhishek Mande how being gay Indian American has shaped his worldview and contributed to his first book.

Debutante author Rahul Mehta tells Abhishek Mande how being gay Indian American has shaped his worldview and contributed to his first book.

Tucked away in a garage in one of Mumbai's upscale suburban lanes is a brightly coloured store, the entrance of which has a curtain made of plastic egg racks. It is, you are told, the first LGBT store in Mumbai.

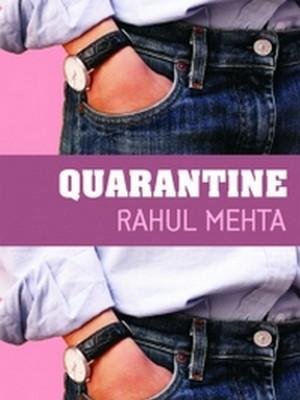

It is apt therefore that a reading of short stories written by an Indian American gay author be held here. Rahul Mehta the centre of attention occupying a prized spot in the 200-odd sq feet space reading out passages from his book, Quarantine.

Mehta has been travelling and looks washed out at the end of a seemingly long week.

The previous evening he was reading from the book at a swanky bookstore in a glitzy downtown shopping plaza. Nearby, a band was playing its music, promoting perhaps their new album. Mehta's throat is hoarse from reading out aloud amidst the din to make his voice heard.

For Mehta, a lecturer at Alfred University in Western New York it has been a long journey. It took him nine years to finish this book, a long time for a story collection by any standards. But there is some poetic justice to this -- there are nine stories in the collection.

These stories are as much about young gay Indian men living in America as they are about people on the fringes of the society trying to come to terms with the world around them.

Mehta, like his characters, considers himself to be something of an outsider. Born and raised in West Virginia, the author, who is in his late thirties, says he did not know that openly gay people existed till he was almost 18 years old!

"There simply wasn't a single outspoken gay person I knew of! Gay characters were yet to make their appearances in television and films (the most popular television show with a gay character Will and Grace hit the screens only in 1998). So my early years were spent in questioning my identity as an Indian living away from India on the one hand and being gay on the other," he says.

Dilemmas such as these and years spent outside of the mainstream have shaped Mehta's worldview. "Most of my characters are marginalised in some way or the other -- some are gay others include people young and old trying to assimilate in the mainstream."

The first story in Mehta's collection for instance is about an old Indian grandfather having to settle down with his son in the US. He chooses to live in the basement and makes his daughter-in-law's life miserable. It is only much later in the tale you see a humane side to him and realise that it has been the only way he knew to cope with the loneliness and the years of existence that stretched ahead of his tired eyes.

Characters like this one are found aplenty in Mehta's book, many showing years of labour. If you read carefully, you can also put a year to the setting of some stories. And even though it doesn't necessarily serve as a chronicle of changing times, Quarantine does reflect the consistent efforts of a man who always wanted to publish a book.

The foundation of this was perhaps laid much before Mehta realised it. He says, "My mother was a librarian and I grew up in a library! I'd return from school and instead of going home, would spend the time with my mother at her workplace. Books were an integral part of my growing up experience. The powerful thing about art and literature is its ability to help us as individuals to feel less alone in the world. When you see something in a novel and story you relate to, you feel less lonely."

It would be a while however before Mehta, then a student, would be able to find a book he would be able to completely relate to.

"I was in graduation school when I attended my first LGBT meeting. I was very nervous and headed straight to the door soon after it was over. Just then I felt a tap on my shoulder. It was the organiser of the meeting. She was an Indian. Just as me, she was surprised to see a desi there. After that she took me under her wing. She took me around bookstores and introduced me to gay literature."

And that was how Mehta laid his hands on books like Tales of the City and others that had gay characters. The idea of becoming a writer was beginning to take shape.

Mehta insists that in all his years of growing he never really felt persecuted. "Like all schoolboys, I got called 'faggot' a lot. But when you are one it feels very different. There were a couple of kids who figured (I was gay) and tormented me. But then again everyone gets bullied in school," he says.

If he did feel traumatised in school the author doesn't talk about it. However he confesses that 'there was an othering that happened'. "It might have to do with the fact that no one ever had seen a gay Indian American person! The people I grew up with in West Virginia were kind and generous and open," he adds.

Did he ever feel persecuted? You venture somewhat uncertainly.

"I didn't care. No more so than anyone else."

Yet when it was time to come out of the closet, Mehta chose to hide behind a pair of sunglasses. He chose a bustling spot and occupied a park bench with his mom. Perhaps he did care.

Mehta has written of this moment as a blogpost for his publisher's website. He says he remembers the day vividly. The idea of opting for a public spot was because he wanted it to be 'somewhere loud, with plenty of noise around us'.

He writes: When I told my mother, she was surprised, which in turn surprised me -- how could she possibly not know. If she was upset, she hid it behind her sunglasses. She said something about understanding that I was born this way. She said she was glad that after graduation I was moving to New York City, where I could find a "gay-positive community." I asked her where she learned the term "gay-positive community" and she smiled and said, "Oprah."

His Oprah-loving mother slowly but steadily broke the news to all their relatives in the US. The senior Mr Mehta was the last to know. For the longest time his relatives in India were kept in the dark too.

Recently his extended family from Mumbai came to his book reading at the shopping plaza. Significantly almost everyone was from the older generation, patiently listening to their nephew making a statement amidst the commotion. They probably also shook hands with his partner, Robert.

It was a closure of sorts for Mehta and also perhaps a new beginning.

Before we start the interview, he has already telephoned some of his Mumbai-based relatives. He wants to reach out to them before they go off to bed, visit them the next morning just to thank them for being at the launch and show their support.

Much later, digging into his pizza, Mehta tells you the importance he lays on human relationships. His life, he points out, isn't arranged around 'practical financial stable considerations'.

"I live an artiste's lifestyle. All my initial jobs were pay-the-rent kinds. I wrote for magazines, worked in a publishing office and took up other such jobs that would help me just about stay afloat. At the same time, they would give me enough time to write."

And write Mehta did. "One of my stories ran into a hundred and twenty pages! I had to edit it drastically! I spent a lot of time on my stories, wrote them, re-wrote them before settling on the final draft."

The stories would be published in various journals. A scout for Random House happened to read one of them and contacted Mehta. For a first-timer, he was undoubtedly luckier than most others who have to wait out for years before their manuscripts are published. The struggle if there was any was in having to complete the book in the given deadline, something he had to labour harder for.

The stories would be published in various journals. A scout for Random House happened to read one of them and contacted Mehta. For a first-timer, he was undoubtedly luckier than most others who have to wait out for years before their manuscripts are published. The struggle if there was any was in having to complete the book in the given deadline, something he had to labour harder for.

Mehta quotes one of his seniors who warned aspiring authors about the extreme hardships they'd have to face in the world. Those who still dare to say they do, she welcomes them with open arms. "You just have to keep trying," he spells out the obvious.

You ask him how his parents have taken to his lifestyle and if his father managed to read his book.

"The biggest challenge for my father has not been as much about coming to terms with my being gay but more so with the way I live.

I haven't as yet bought a house. I don't make a lot of money. He wants me to settle down, as does my mother. They ask me when we were planning to have a baby! These things, I realise, matter much to desi parents.

As for the book, I think he has read the most of it. He didn't give me any particular feedback but I know that he cared because he read it."

After meeting his relatives the next day, Mehta and his partner will fly out of Mumbai. The two will head North like they always do whenever they're in India. They'll spend a few weeks trekking in the Himalayas where Mehta finds himself at peace. He likes being away from the madding crowd, walking the lesser-trodden paths.