'The harmful side effects of what we call 'management toxicity' are affecting more and more Indians,' note Jeffrey Pfeffer and M Muneer.

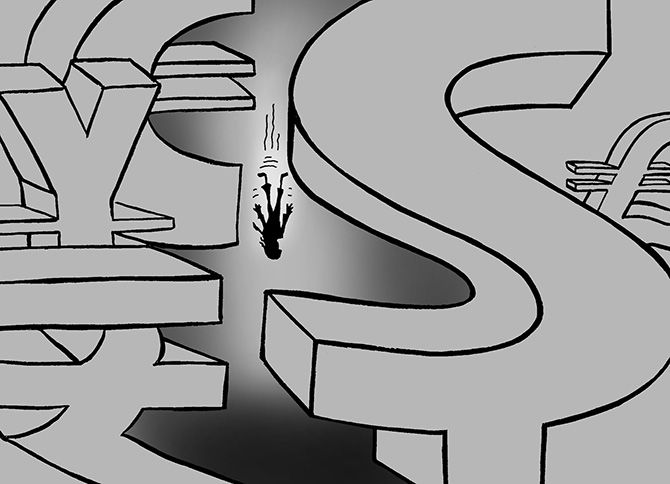

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

In a shocking incident a couple of years ago, Karl Slym, then MD of Tata Motors, jumped off his top-floor hotel suite in Bangkok.

Last year, the COO of Encyclopedia Britannica plunged down the ventilation shaft of his apartment building.

Still earlier, a young CEO of SAP India succumbed to a massive heart attack, reportedly owing to sleep deprivation.

Two recent studies have found that depression, anxiety and stress prevail among 43% to 46% of employees in India's private sector.

Demanding work schedules, high pressure on KPIs linked to higher perquisites, and the always-on mobile phone syndrome are the top three culprits.

Sleep apnea, relationship issues, poor eating habits, lack of exercise, lifestyle issues such as EMI troubles and peer pressure to maintain luxurious lifestyles complete the list.

The harmful side effects of what we call 'management toxicity' are affecting more and more Indians.

Some one-eighth of the 800,000 suicides across the world annually are literate Indians -- potentially employed or employable.

India is the world capital for diabetes, and cardio ailments are affecting more and more Indians in their thirties.

You don't have to work in a coal mine or chemical plant to incur health hazards.

In fact, blue-collar occupational hazards have been largely eliminated after the introduction of stringent health, safety and environment (HSE) processes in most companies.

Reprising a lesson from the Quality Movement that 'what-gets-measured-gets-affected', companies pay attention to workplace fatalities and incidents, such as falls or chemical spills, where bodily harm can be readily ascertained and benchmarked globally.

Unfortunately for white collar workers, the stress at work is intangible, and doesn't get measured.

This inevitable part of contemporary workplaces just keeps getting worse for almost all jobs, resulting in an ever-higher physical and psychological toll.

The American Psychological Association's 2015 report noted that the top two sources of stress were money and work.

Another poll reported that nearly half of employees surveyed missed time at work from work-related stress, and 60 per cent said that stress had made them sick.

Yet, a surprising number of recent studies have shown that performance is not positively related to work hours.

The greater the work hours, the lower the productivity per hour worked.

Just working more doesn't accomplish much.

A Harvard Business Review article has argued that even though managers seem to 'want employees to put in long days' and 'respond to their e-mails at all hours,' such policies backfire for people and companies.

There is a lot of evidence that long work hours are hazardous:

A review of 27 empirical studies found that long work hours 'are associated with adverse health' including 'cardiovascular disease, diabetes, disability'.

Working overtime was associated with a 61 per cent higher injury rate.

A meta-analysis of 21 studies reported 'significant positive mean correlations' between overall health symptoms (physiological/psychological) and hours of work.

Even as organisations encourage management practices that sicken and kill employees, they also suffer, because toxic management practices do not improve profitability.

Unhealthy workplaces diminish employee engagement, increase turnover, and reduce job performance, while driving up health insurance and healthcare costs.

If anything has to change, the following things will need to occur:

First, employees must comprehend what constitutes health risks in their work environments.

That includes the psychosocial risks that are more damaging than physical injury risks.

They must choose their employers, at least partly, based on the stress-related dimensions of work that profoundly influence their physical and mental health.

Second, employers will need to determine the costs of their toxic management practices in terms of both direct medical costs and indirect costs via lost productivity and increased employee turnover.

That understanding will be a necessary first step toward change.

Third, governments will need to take action on the externalities created when enterprises retrench people who were physically and psychologically damaged at work.

The IT industry is a classic example here.

The public costs of privately created workplace stress have already prompted policy attention and action in UK and the Scandinavian countries.

With 'Modicare' being launched, it is in the government's interest to reduce unnecessary -- and preventable -- health care costs.

Fourth, societies will need social movements that advocate that 'human sustainability' and better work environments are as important as environmental sustainability.

Dumping pollutants into the air, water and ground have been rampant, but of late people have begun fighting for a better environment and made companies pay for the damage.

Public movements have forced governments all over the world to pass laws and develop norms restricting pollution. Delhi is an example of 'too little, too late' in terms of public movements.

Fifth, employees need to learn how to say 'No' when it is right to say so.

It is also important to adhere to time management principles.

We seem to be creating truly lose-lose work environments, with people making themselves sick for no other reason than to demonstrate their 'commitment', risking their lives and health for their employers.

If we are serious about building healthier societies, the time to act is here and now.

It just is not worth dying for a better pay cheque!

Jeff Pfeffer is a best-selling author and professor of organisational behaviour at Stanford University. M Muneer is co-founder and chief evangelist at the Medici Institute.