Shane Warne's tell-all autobiography is every bit as controversial and engrossing as his cricketing career, notes Dhruv Munjal.

One of the more enjoyable bits in Shane Warne's autobiography does not even feature Shane Warne.

Some 160 pages in, he finally lifts the lid off the time Herschelle Gibbs famously put down Steve Waugh in the 1999 World Cup. '...And, by the way, it's a load of crap that he said to Herschelle, "You've just dropped the World Cup." It's totally made up.'

Warne's annoyance is understandable: Apocryphal nonsense of this sort is legitimised by users on social media, and this particular tale has become infuriatingly common in subsequent years.

How do you drop the World Cup in the Super Six stage -- with so much of the tournament still remaining -- anyway?

Warne's own story, of course, is anything but spurious.

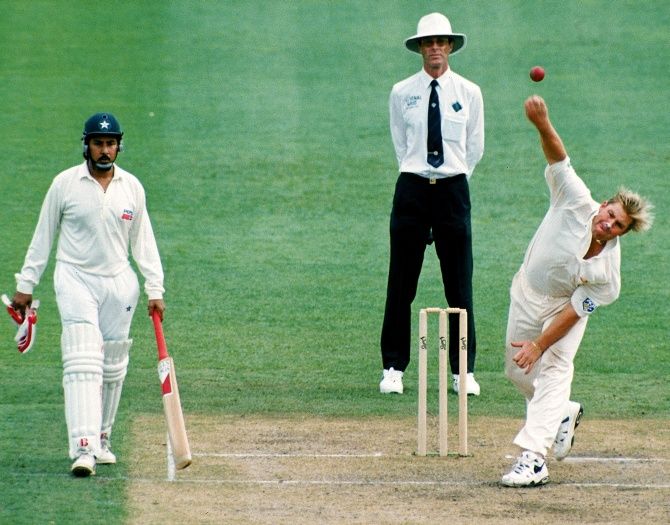

He has lived the life: From driving trucks and delivering beds to cementing his place as the most extraordinary spin bowler of his time, possibly of all time.

This ascent was punctuated by colossal errors in judgement that led to drugs and dealings with bookies; odious sexual encounters that made tabloid headlines; and a determined -- but mostly unsuccessful -- battle to stay off copious amounts of food, booze and cigarettes.

Warne's has been the archetypal bad-boy adventure.

He may be more removed from the inescapable lens of scrutiny now, but Warne continues to be a maverick personality unafraid of inviting embarrassment and risking his reputation.

No Spin is a mere extension of that persona. As he was on the field, here's a guy ready to take you on, this time with his words.

To Warne's considerable credit, this is not a piece of sanitised drivel from which emerges a remarkable cricketer with impeccable character.

Warne's genius was a highly flawed one and he is quick to acknowledge the fact.

Broadcaster and former Hampshire captain Mark Nicholas, who has co-authored the book, mentions in the introduction that No Spin is 'written mainly in his (Warne's) vocabulary, as a stream of consciousness'.

The book's Aussie lingo confirms Warne's stamp; this is unlike the nuanced, evocative writing

that Nicholas has exhibited in his time as a noted columnist.

Richie Benaud's brother, John, for instance, is 'a beauty of a guy, a ripper bloke'.

He also, quite fascinatingly, came up with the term sledging. 'Yeah, whatever, mate' is another of those characteristically Aussie expressions that Warne uses throughout, mostly to silence people calling him out for some of the questionable stuff he did during his career.

The Aussie-ness is splendidly complemented by an engaging narrative that is filled with stories from a career that routinely oscillated between wonder and disrepute.

According to Warne, the 'Ball of the Century' that bamboozled Mike Gatting was a 'fluke' and 'something meant to be'.

Later, he recalls how Salim Malik invited him to his hotel room and offered him $200,000 to draw a game against his Pakistan team in Karachi in 1994.

Warne refused, Australia lost the match in the most dramatic circumstances, and Malik was eventually charged.

Funnily, Australia's nickname for Malik was 'The Rat', more for the way he looked than anything else. He fit the bill either way.

More than Warne the celebrated cricketer, the picture that emerges from this book is of Warne the suburban Melbourne kid who refused to take himself too seriously, and built a career in cricket only because football -- the Aussie rules kind -- did not work out.

He worked assiduously on his craft not because he was earmarked for eternal greatness, but because after a point he felt that cricket was something he could become good at and make a living from.

This insouciance often aggravated Warne's naivety.

His accepting $5,000 from a stranger who was later found to be a Sri Lankan bookie, or his popping of a water-loss pill that turned out to be on the banned substances list, Warne remarks, were nothing but acts of gross stupidity.

Deep into the book, Steve Waugh makes the customary villain's appearance.

The duo's enmity has snowballed in recent times, and it seems that Warne still isn't quite ready to forgive his former captain for dropping him against the West Indies in Antigua 1999, or for enforcing the follow-on in the Kolkata Test of 2001, or for asking his team to turn out in their Baggy Greens to show support for Pat Rafter at Wimbledon.

While this forthrightness makes the book tick in most places, a lack of genuine contemplation makes you wonder if Warne could've achieved much more with this attempt.

In Warne's defence, though, he's hardly a philosopher, and asking him to pull off something unnatural would have defeated the purpose of a tell-all autobiography.

At his core, he seems the 'no regrets' kind of guy who would rather accept mistakes and move on, than offer cursory rebuttals.

Like the time he was found with two women in only his Playboy undies during a county stint with Hampshire, photographs of which appeared in News of the World after one of the women sold the story.

'I've always struggled to deal with these tabloid stories. What sort of a person hides a camera and then sells the pictures... yes, I'm into women, which has cost me massively, time after time,' writes Warne of the episode.

Despite these colourful interludes, No Spin's real value lies in Warne's dissection of his art of leg-spin. Bowling over the wicket, bowling around the wicket, bowling into the rough, perfecting the flipper, working angles, setting up batsmen -- Warne's tutorial on the demanding craft is a masterclass.

Even as the book, just like its subject, suffers from imperfections, No Spin paints a quite brilliant picture of a life spent in the limelight.

Warne is bold, impenitent and utterly readable -- the title may not indicate much turn, but for over 400 pages, the wizard in Warne has given this one a real rip.