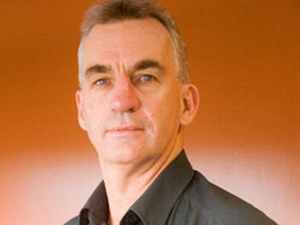

Haresh Pandya, paying tribute to friend and noted columnist Peter Roebuck, says the Englishman's untimely death is an irreparable loss not only to cricket journalism, but also sports literature.

Cricket writing can be an art form in the hands of the most talented of wordsmiths. But reading many of Peter Roebuck's pieces and essays you felt that he belonged to a select few who elevated cricket writing to not only an art form but turned it into almost a literary genre.

Having played cricket professionally and rubbed shoulders with many of the best in the business, Roebuck's approach to the game and its practitioners was more sympathetic than that of many hardcore professional journalists. But he never minced words when criticism was necessary; the only thing was he didn't like to pounce on the players concerned. While others used the butcher's knife, Roebuck managed with the surgeon's scissor. Yet, the effect was the same.

Roebuck was the most unbiased of cricket writers imaginable. He had no favourites. In fact, he never liked to mix and mingle with players. Personally and professionally, he always drew a line. It enabled him to express his views freely and without fear. Most players, who know the professional needs of journalists, took Roebuck sportingly. Even Ricky Ponting, who had been the butt of Roebuck's criticism towards the end of his captaincy innings.

The celebrated cricket writer had a connoisseur's penchant for the niceties and subtleties of English and he knew fully well how and when to employ the language judiciously. Roebuck, who taught English and read voraciously on a wide range of subjects, not just literature, was well aware of the fact that even the smallest and simplest of words have great power of expression. Given his innate flair for writing, he developed his own inimitable style -- lucid, smooth and transparent.

Use of irony came as naturally to Roebuck as employment of the square-cut to Gundappa Viswanath in full flow. Roebuck's usual, trademark small sentences sometimes carried a devastating irony or two, which average readers would fail to grasp. Thankfully, he didn't indulge in too many literary and other analogies, which explained why he was more comprehended and admired by most, including fellow-cricket writers.

A highly opinionated cricket writer, Roebuck's judgments and views weren't always true or perfect. He had often to eat humble pie. He was frank and honest enough to admit his mistakes or poor judgment. He had almost lampooned Virender Sehwag for what he called his "rustic technique" and "wayward or no footwork at all" in the initial stage of his career. But as Sehwag went from strength to strength and began massacring the bowlers and plundering runs, Roebuck had no other option but to join the bandwagon and praise the "monster".

We were together in Pune covering the 1996 World Cup match between the then formidable West Indies and the lowly Kenya. After Maurice Odumbe and company were bowled out for 166 in 49 overs, Roebuck left not only the press-box, but the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium, feeling sure that it would be a "cakewalk" for the Caribbeans to "crush" the Africans. His idea was to see Kenya's humiliation from the comfort of his hotel room.

But when the West Indies lost five key wickets, including Brian Lara, in a jiffy, Roebuck took a cab and hurriedly arrived at the ground. By then Richie Richardson and company had lost another three wickets. 'It was one of the blunders of my life to underestimate Kenya and take a West Indies win for granted,' he told me when the Caribbeans were sent packing for a paltry 93 in 35 overs, triggering one of the biggest upsets in the history of cricket.

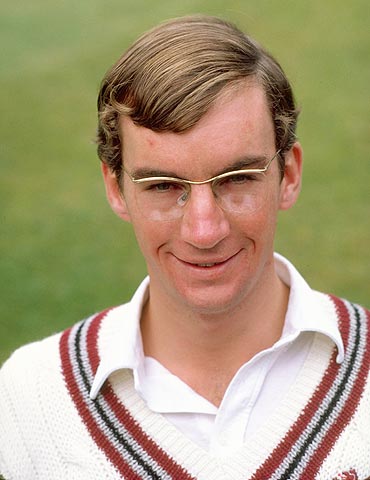

Roebuck, who usually talked about any player freely and fearlessly, preferred to avoid discussing Ian Botham, Vivian Richards and Joel Garner -- the three musketeers of Somerset CCC he had built brick by brick and taken to new height of success in the early 1980s. The triumvirate left Taunton for good in a huff after falling foul of Roebuck, who wanted to make it a point that they weren't greater than the game or Somerset CCC.

'I know you are a friend. I don't doubt your intention or integrity. Yet, I've to be careful. If I say something and it appears in the media in a controversial or sensational manner, it would spell trouble for me. Why open a Pandora's box when the whole issue is long buried?' he said, when I asked him to tell me in detail what exactly had transpired between him and his former team-mates.

Though apparently a simple, unassuming man, Roebuck always gave the impression of being surrounded by some sort of mystique, both in his letters and during our personal meetings. His horrible handwriting and illegible scrawl probably mirrored his inner complex personality.

He never tolerated fools; he always demanded 100 per cent effort and second best had no place in his outlook. This explains why he was the best and the most admired and respected cricket writer of the modern era. For all his alleged complexities and the mystery surrounding his real persona, it must be emphasised that he was a gem of a man -- frank, friendly, kind and often generous to a fault.

Not too many know that Roebuck had a foster daughter in Kolkata. Malabika Das (born January 20, 1985) arrived at SOS Children Villages after being found wrapped in a piece of cloth.

'She likes dancing, singing and is, apparently, full of mischief,' he told me in the early 1990s, requesting to send her 'useful things' like clothes and books on his behalf from time to time. I did it to the letter and dear old Peter was unnecessarily but always 'so grateful'.

Roebuck may not have achieved the heights of Neville Cardus and John Arlott, arguably the greatest cricket writer and broadcaster respectively, but it's fair to say he was just somewhere between them. He was an intellectual who fell in love with cricket and played it professionally and wrote on it passionately. His tragic, untimely death is an irreparable loss not only to cricket journalism but also sports literature, for he penned some real classics of the willow game.