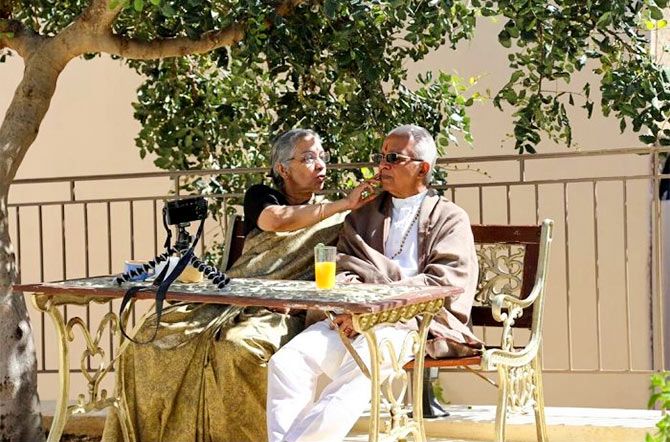

Bharata Natyam legends Shanta and V P Dhananjayan discover they are a national sensation after their Vodafone ads.

Nikita Puri encounters a couple who believe in breaking moulds.

For the past five decades at Chennai's Bharat Kalanjali, one of India's premier bastions for Bharata Natyam, mornings have begun with the lighting of the lamp.

This is invariably followed by the sound of feet moving to the nattuvangam, simply described as a stick-like instrument intended to monitor beats.

The senior-most dancers and gurus here also double as the academy's founder-directors, Shanta and Vannadil Pudiyaveettil Dhananjayan.

Made formidable by their talent and dedication to the arts as the 'dancing couple of India,' the Dhananjayans are highly revered in the arduous world of classical arts.

The seamless agility and nimbleness of their movements makes it extremely difficult to believe that she is 73, and he 78.

As legendary gurus who have helped shaped the trajectory of Bharata Natyam across the globe and have also been honoured with a Padma Bhushan in recognition of their work, 'cute' isn't exactly a term the Dhananjayans are used to hearing.

Most call him 'Sir', a few call him 'Anna' (Tamil for elder brother). Shanta is 'Shanta Akka' (elder sister).

Over the past few weeks, complete strangers, including small children, have walked up to them wondering if they were the 'cute couple from TV.'

In a six-part advertisement series meant to promote Vodafone's Supernet 4G, the Dhananjayans shine as the uber-cool elderly couple called Asha and Bala.

In Goa for their 'second honeymoon', Bala is seen getting Asha's name tattooed on his arm, and she tries para-sailing.

They are seen lounging on the beach chairs under giant umbrellas, and dancing to 'modern' music on a boat in the midst of a young crowd.

They are also seen riding around on a scooter, asking one Goan after another the way to the 'Dil Chahta Hai fort' and getting contrary directions.

The Dhananjayans are used to being recognised by art connoisseurs, but the response to these ads have left them thoroughly surprised.

Soon after they had finished watching Baahubali: The Conclusion, the couple found themselves saying 'yes' to requests for selfies with complete strangers.

"We are getting calls from abroad too. We did the ads only because we though it'd be fun," says Shanta.

Their definition of 'fun' includes getting out of their comfort zone.

In a small room at the Vasco da Gama railway station, Dhananjayan put aside his traditional veshti (dhoti) and jippa (kurta) and switched to half-sleeved shirts and shorts; the last time the guru wore shorts was when as a young boy.

The six-day shoot was a taxing one, but the Dhananjayans "could do it because their own schedule and discipline is very demanding," says C P Satyajit, one of their two sons and also an automobile photographer.

The Dhananjayans make the ad shoot look easy, says Tulsi Badrinath, one of their students, "but beneath it is the same discipline and professional approach to work that they exhibit in all areas of life."

Dhananjayan even tried learning to ride a scooter for the shoot, something he has never attempted before; the team at Nirvana Films (the production house behind the animated Zoozoo cartoons) also brought in a three-wheeler to help Dhananjayan. "But it just didn't happen," he recalls.

In the crowd that was cheering on as Dhananjayan was attempting to ride was "a very nice man called Milton", a government official.

"He resembled Dhananjayan so much that the team used him in the scenes which had long rides on the scooter; it was just by chance that he was there," recalls Shanta.

In the lives of the Dhananjayans, a lot has seemed to have happened "by chance."

Much like Milton coming out of the blue, the phone call that got them involved with this shoot was unexpected.

Decades ago, the founder of Chennai's famed cultural academy Kalakshetra, Rukmini Devi Arundale, had assigned Kathakali exponent Chandu Panicker the task of finding a young male dancer who could learn Kathakali and Bharata Natyam.

Panicker had already found a suitable student when he met Dhananjayan's father, a school master.

Feeding a family with eight children was hard, so Panicker was asked if he could also take Dhananjayan, since he had an interest in Sanskrit dramas and poetry.

He was barely 14 then, and Panicker strictly told his father that if the boy didn't meet Rukmini Devi's standards, he'd have to return.

Dhananjayan went on to stay there, on scholarship, for the next 12 years.

When Dhananjayan first came to Kalakshetra in 1955, he spoke only Malayalam, so Panicker introduced him to another Malayalam-speaking student: This was eight-year-old Shanta who had come here a year ago.

"She was the first girl I met at Kalakshetra and I've loved her ever since then," says Dhananjayan.

By the time Shanta was 12, she had also made up her mind to marry Dhananjayan.

When Shanta was 18, she left for Malaysia, where her family lived.

They regularly wrote to each other. "I would always sign my letters saying 'Your loving sister, Shanta' because our communication was monitored and there was censorship," recalls Shanta.

She returned and they married in 1966.

Many of the students groomed in Bharata Natyam under the strict tutelage of the Dhananjayans have their own dance schools now, transforming the Dhananjayans into globetrotters who split their time between teaching at Bharat Kalanjali and travelling with their productions.

Reportedly, sitarist Pandit Ravi Shankar was so moved by one of their performances that he invited them to collaborate with him.

After that, in the early '90s, the Dhananjayans did choreograph Shankar's dance/theatre-ballet on drug abuse; it was called Ghanshyaam -- The Broken Branch.

During all of their travels, Dhananjayan would regale their students with tales of their life-long romance, recounts Badrinath in her book Master Of Arts: A Life In Dance (Hachette India, 2013).

Stories paint Dhananjayan as an epitome of utmost discipline, a man who highly values time and sticks to his schedule even if 'VIPs' haven't turned up on time.

Till date, he regularly writes to newspapers about pressing national issues, like the Cauvery water conflict, irrespective of whether his writing is published or not.

"My father is the more outspoken one," says Satyajit. "He is a very no-nonsense person while my mother is more forgiving, softer."

But neither of them tolerates laziness, emphasises Badrinath.

"Akka is more patient and gentle. Sir is a bit more forbidding: I have been his student for more than 40 years and I am still scared of him," she says.

One of the hallmarks of Dhananjayan's performances is how he "has always looked for the right mythological characters as vehicles for his artistry," says Badrinath.

The day after one of Dhananjayan's performances at Chennai's Narada Gana Sabha in 2012, in Chennai, Badrinath recounts in her book how her guru, his grey hair freshly shampooed, entered the class.

'Not knowing how to tell him just how superb he was, we burst into spontaneous clapping. This is my continual good fortune; that the lord of dance whom I beheld yesterday is my guru,' Badrinath writes in her book.

Here, she also chronicles how Dhananjayan had to battle prejudice to rise up in a world where men were not encouraged to take up Bharata Natyam.

It took years of hard work, self-belief and the support of his wife Shanta to reach where he has, says Badrinath.

As they made their way forward, the Dhanjayans, notes Badrinath, have chosen their themes with care, and always "preferred to present bhakti or devotion as male, rather than in the role of a nayika."

Over time, many of the prejudices against a male dancer slipped away, giving way to packed halls and ardent fans.

In 1962, when news of Chinese forces storming across India's borders swept through the nation, marking the beginning of the brief Sino-Indian War, a 23-year-old Dhananjayan had made up his mind to join the army.

Shanta was still in Malaysia then and, if a teacher at Kalakshetra hadn't intercepted Dhananjayan and stopped him from going to Avadi where the military cantonment was, this story is likely to have been very different.

For the Dhananjayans, as well as for Bharata Natyam.