Some of the World Bank's suggestions to hold back the predicted tide of fresh poverty appear to run counter to the economic policies of Narendra Modi's government

Climate change could effectively negate India’s economic progress, pushing 45 million Indians into extreme poverty over the next 15 years, according to a World Bank report published last month.

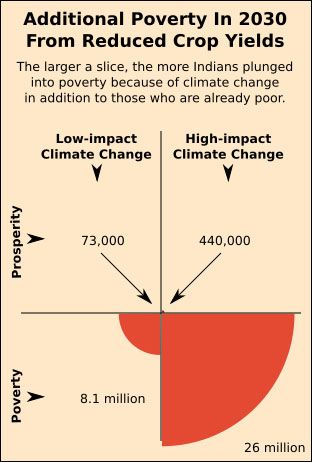

In the absence of climate change, the World Bank report sees 189 million Indians living in poverty (i.e. on less than $1.9 or Rs 127 a day) by 2030. Climate change could push that number to as high as 234 million.

There were 263 million Indians living in poverty in 2011, according to recent World Bank estimates using a revised $1.9-a-day poverty line.

The situation where 45 million become poor because of climate change is just one of the scenarios described in the World Bank report “Shock waves: Managing the impacts of climate change on poverty“.

The unfolding dilemma for Narendra Modi

Some of the Bank’s suggestions to hold back the predicted tide of fresh poverty appear to run counter to the economic policies of Narendra Modi’s government. For instance, even as the government reins in health funding–as IndiaSpend reported earlier this year–with lesser money for states even after devolution, the report suggests greater investment in health infrastructure.

This includes more subsidised healthcare, health insurance and systems to warn about emerging health crises. A recent move in India to revamp a health insurance scheme for the poor, the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana, is a step in the right direction.

Other suggestions–to make assistance prompt, scalable and targeted–are in line with the government’s move to reform India’s vast subsidy programme.

“We published this report…to remind everybody…that the climate change challenge is not only about the environment and the climate,” said Julie Rozenberg, co-author and World Bank economist. “It is also about the future of poor and vulnerable people and our ability to eradicate poverty. And for countries like India, failing to reduce global emissions of greenhouse gases could threaten prosperity and the future of millions of people.”

Four scenarios for India and the world

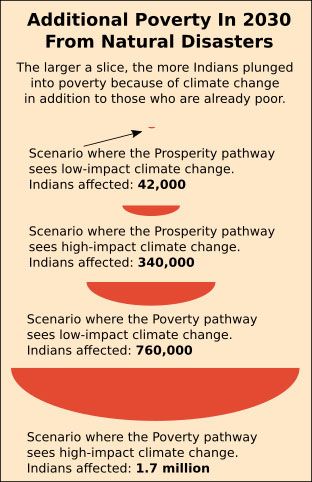

Poverty and climate change affect each other in various ways, and given the uncertainty about how things might play out over the next 15 years, the report has built four scenarios of how India, and the world, could look like in 2030.

These scenarios are different combinations of a) low-impact and b) high-impact climate change and of socio-economic pathways described by the report as a) ‘poverty’ (its features being high population growth, low GDP growth, and high poverty and inequality) and b) ‘prosperity’ (low population growth, high GDP growth, and low poverty and inequality).

Source: World Bank

Three ways in which climate-change drives poverty

There are three main factors triggered by climate change that could drive people into poverty: a drop in crop yields, natural hazards, poor health and labour productivity.

There are three main factors triggered by climate change that could drive people into poverty: a drop in crop yields, natural hazards, poor health and labour productivity.

The first factor: Climate change could see crop yields dropping (the worst-case scenario has global crop yield dropping by 5 per cent by 2030) because of which food becomes costlier. People then end up spending less on other things or cutting down on how much food they have.

The recent examples are the food price spikes that pushed 100 million in 2008 and 44 million in 2010-11 into poverty around the world.

The second factor is poor health and productivity. “Warming of 2-3 degrees Celsius could increase the number of people at risk from malaria by 5 per cent and diarrhoea by 10 per cent (around the world), ” said the report.

Another impact we could see is of stunting as food becomes less affordable and people are unable to meet their nutritional needs.

Increase in temperatures could also see a loss in labour productivity of 1-3 per cent, the report said.

Having to spend on health to treat diseases is what hits people the most. People in poor countries have little access to financial assistance - either in terms of loans or insurance.

Having to spend on health to treat diseases is what hits people the most. People in poor countries have little access to financial assistance - either in terms of loans or insurance.

They also pay “more than 50 per cent (of their budget) in out-of-pocket [health] expenses,” according to the report and end up poorer as a result.

The third factor is the increasing occurrence and intensity of natural hazards such as droughts, river flooding and higher temperatures.

In the worst-case scenario for 2030, the number of people exposed to droughts worldwide could increase by 9-17 per cent over a no-climate-change scenario and those exposed to river floods could increase by 4-15 per cent.

These natural hazards affect the economically vulnerable relatively more than the rich.

The things they own, such as housing or livestock, are more exposed to such hazards. These assets, built up over decades, could vanish in an instant.

As in the case of the health factor, because the vulnerable have less access to financial help of any form, they have little ability to recover from such shocks.

What governments can do

Even if governments tried to avoid the worst-case scenario by adopting some kind of climate-change mitigation policy now, it would not amount to much, as changes that will take place by 2030 are a result of past emissions, and new policies could have only a long-term effect but not as soon as 2030.

Even if governments tried to avoid the worst-case scenario by adopting some kind of climate-change mitigation policy now, it would not amount to much, as changes that will take place by 2030 are a result of past emissions, and new policies could have only a long-term effect but not as soon as 2030.

Maybe nothing can be done about the effects of climate change but governments could do something about the number of people falling into poverty. They could do this by giving protection and assistance to those who are the most at risk.

Such assistance should be: prompt (if support is delayed, families could try to sell off what they own to survive), scalable (the effort involved must be responsive to the severity of the shock) and targeted (to ensure that, even among the vulnerable, the program covers those who need help most first), the report said.

The report recommends the use of more climate-resistant crops and livestock to counter the drop in agricultural productivity. It also suggests introducing practices such as polyculture (combating pest resistance by growing multiple crops in the same field) and improving awareness of these practices among farmers. Another step would be to improve transport so that farmers have better market access.

As for natural disasters, the recommendation is to improve protective infrastructure such as dykes and drainage systems to protect against floods and also introduce early warning systems. To help people deal with floods better, the report suggests granting people property rights so that they have an incentive to make their houses stronger and more resilient.

When it comes to post-disaster relief, establishing large work programs could provide the affected a steady job and income, the report said.

Photographs: Reuters. Graphs: World Bank

Indiaspend.org is a data-driven, public-interest journalism non-profit