Be it consumer products, lifestyle or entertainment, spiritual gurus are stepping into business and are finding success

Amritha K is a homemaker based in the central suburb of Ghatkopar in Mumbai. Like most housewives, affordable grocery shopping is an important item to manage. She keeps a hawk’s eye on quality but never fails to bargain for that extra rupee of discount from the grocer.

“I’ve heard the products are of good quality and reasonably priced,” she says. “But, there is such a crowd there that I don’t know when I will be able to find the time to go there.”

This is a dilemma that confronts a number of middle-class households in India. Yoga guru Ramdev’s Patanjali Ayurved has presented itself as a credible alternative in fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), compelling many to switch from age-old preferences and brands.

“Herbal and ayurveda is one aspect of what Patanjali stands for,” says Aditya Pittie, chief executive officer, Pittie Group, a distributor of Patanjali products in modern and general trade.

“The success of Patanjali has to do with its positioning on health. The fact that Swamiji (Baba Ramdev) is a yoga guru who has always canvassed for good health is not lost on people. This is what is helping sales.”

To many, Patanjali Ayurved, which has targeted a Rs 5,000-crore (Rs 50 billion) turnover this financial year, is symptomatic of a trend sweeping the country today: The entry of babas into business. Whether consumer goods, lifestyle or entertainment, spiritual gurus are no longer averse to stepping into business – doing it confidently and even emerging successful.

A string of them

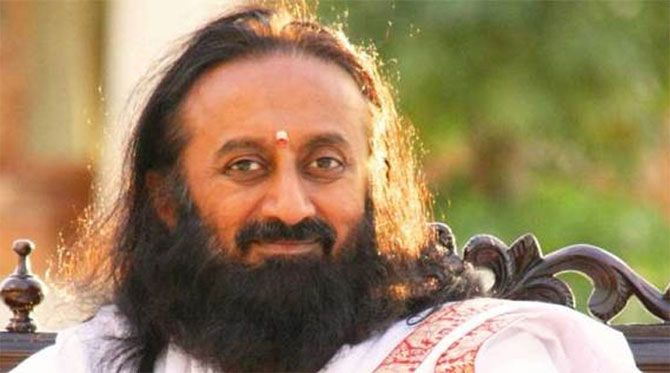

Take Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, for instance. A recent report by brokerage Edelweiss says that Sri Sri Ayurveda, ayurvedic FMCG arm of Sri Sri’s Art of Living Foundation, is expanding into more categories and has begun to use mass media, point of sale advertising and push its digital presence aggressively through its app, e-store and via e-commerce portals.

Additionally, Sri Sri Ayurveda is looking to ramp up distribution of its products by taking it to 2,500 stores by 2017 from 600 stores now. The next leg will see it get into modern trade as well, talks for which are currently on, the report said. Future Group’s CEO Kishore Biyani said recently he was open to distributing Sri Sri’s products.

“Sri Sri Ayurveda has a wide range of products in personal care, diet supplements, food and accessories. It is planning to expand its presence into breakfast cereals, cookies, atta, oils, spices, ready-to-cook items and a range of organic staples for select markets. Though lagging Patanjali, it has the right ingredients to help grow the ayurveda space, posing competition to other consumer peers,” analysts Abneesh Roy, Pooja Lath and Tanmay Sharma noted.

While a detailed mail and calls to Sri Sri Ayurveda Trust elicited no response till the time of going to press, Devangshu Dutta, chief executive of consulting firm Third Eyesight, says the coming together of religion and commerce is not new.

“If you look at the West, whether it is TV evangelism or other large movements, there is a whole system that has developed around it. A part of this involves the lifestyle of followers, which includes products and services. What we are seeing is an explosion of this in India.”

Tapping followers

Experts say the wave of babas stepping into business is linked to their larger and core ability to tap into a captive base of followers. It serves as the first line of defence for most of them before going mass.

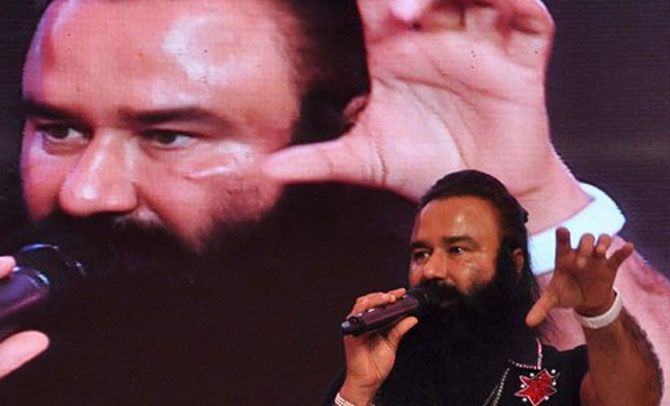

Take Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, chief of Dera Sacha Sauda, a Sirsa, Haryana-based organisation, estimated to have a following of 55 million across India and the globe (Sri Sri is larger at 370 million and Patanjali has 70 million followers worldwide).

Singh, popular in Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan as a rockstar saint, burst into the national consciousness last year, when he directed and starred in two films – MSG: The Messenger and MSG-2: The Messenger.

While the first instalment is estimated to have grossed Rs 126 crore (Rs 1.26 billion) in box-office collections, MSG-2, according to Aditya Insaan, the Dera’s spokesperson, has entered the Rs 500-crore (Rs 5 billion) league recently. “The objective was to convey a social message in an interesting and entertaining format,” he says.

The response to the first two instalments appears to have goaded Singh to direct and star in two more – MSG: Online Gurukul and MSG: The Warrior, to be released later this year.

Additionally, Singh has taken the MSG franchise launching a line of eatables, cosmetics and grocery items this January. A singer, composer and lyricist, Singh also has a line of music CDs, speeches and discourses available for sale. Further plans include taking his consumer products into international markets and looking at means to leverage technology, Aditya Insaan said.

While revenues for both Sri Sri and Dera Sacha Sauda are not available, there is no denying the potential of the business ventures promoted by these organisations, experts say.

“If marketed and distributed in an organised manner, these businesses have the potential to do what a Patanjali has,” Dutta says.

Kishore Biyani, chief executive officer, Future Group, who saw the trend coming earlier, wasting no time to tie-up with Patanjali last year, says, “The customer is king. It is what he or she dictates that counts.”

Other gurus in FMCG space

Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev: Popular with corporates for his spiritual discourses, Sadhguru set up the Isha Foundation in 2012. This has a commercial arm that sells food, personal care and wellness products. Has a strong presence in the south and is slowly expanding to the north in Delhi and Uttar Pradesh

Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS): An institution that runs 800 Swaminarayan temples in India, US and UK, besides Akshardham temples in New Delhi and Gandhinagar, Gujarat. The institution manufactures and markets FMCG products under the BAPS Amrut brand, which is strong with its follower base.

Aurobindo Ashram: A community based in Puducherry which considers spiritual thinker Sri Aurobindo as their guru. The ashram, which produced goods for its own consumption, has now stepped into the commercial market with incense sticks, soaps, candles, perfumes and furniture

Source: Edelweiss/Industry

Global trend

Televangelism: Big in the US. Estimated to be a nearly $2.5-3 billion business; the ecosystem revolves around tele-evangelists, who much like Indian babas and spiritual gurus extend their franchise into merchandise and products

Trappist beer: Brewed by Trappist monks, a Roman Catholic religious order; the beer is popular in Europe and the US and sells under brand names such as Achel, Chimay, Gregorius, Spencer, La Trappe and Orval

Products made by cloistered orders: The West is gradually waking up to products made by nuns and monks, mostly cloistered, who are known to be self-sufficient. Products, considered high on quality, include everything from food to non-food items such as furniture. Made popular by websites such as LaserMonks, Monastry Greetings etc in the US; has a loyal consumer base

Tourism: A massive tourist eco-system revolves around places such as the Vatican, centre of the Roman Catholic Church, Mecca, Jerusalem etc. Tourists visiting the Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum, for instance, estimated to be at least five million annually; earning the Vatican nearly $90-100 million in revenue

Land: Religious groups in general are among the biggest land owners in the world; some like the Church of England have monetised it; to create a $7 billion investment corpus, while others such as the Roman Catholic Church haven't

Source: Industry