By piling more pressure on governments, central banks risk not accomplishing much and yet provoking a political backlash that could threaten their independence

Central bankers who led the charge to pull the global economy from a cliff during the financial crisis now risk becoming bit players, ill-equipped to snap the world out of sluggish growth and its addiction to cheap credit.

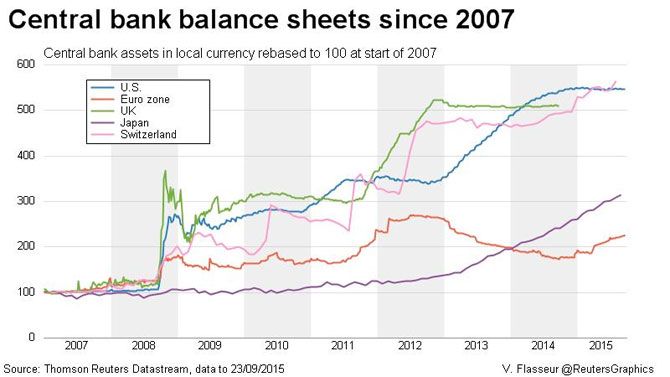

Despite near-zero rates and $7 trillion of monetary stimulus unleashed by central banks in major industrial economies, investment and growth is stuck below pre-crisis levels and tepid demand is hurting developing economies by depressing prices of their commodity exports.

"Memo to the human race: you tried all this monetary policy stuff and at the end of the day it did not succeed in getting you back where you need to be," Paul Sheard, chief global economist for Standard & Poor's, told Reuters. Sheard suggested it might be time for central banks to admit their interest rates are stuck at zero, and for other policymakers to step up.

Essentially central bankers face a dilemma - either lean more on politicians to do more to boost growth or embark on a new round of experimentation.

Both come with risks and uncertain payoffs.

Calls by the International Monetary Fund and others for increased spending on infrastructure, reforms that could open markets in Japan and Europe, or outright fiscal stimulus in countries like Germany, have produced little action since the 2008-2009 financial crisis. By piling more pressure on governments, central banks risk not accomplishing much and yet provoking a political backlash that could threaten their independence.

More experimentation - such as negative interest rates or direct financing of government spending - could deepen concerns that central banks were straying further from their core competences.

Then there is the third, increasingly unappealing option: do more of the same. The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank continue buying securities to spur more lending, while the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England do have an option of resuming debt purchases they wrapped up in 2014 and 2012.

Yet as the IMF noted, Japan and Europe are unlikely to grow any faster without serious structural change.

In fact, Japan probably slipped back into recession last quarter despite $1.50 trillion injected by the Bank of Japan into the economy since April 2013.

In the United States, the Fed's quantitative easing - creating money to buy securities and dramatically boost the reserves that banks could lend on elsewhere - gets credit for stabilizing financial conditions. But policymakers are not sure how much growth it produced and what more could it accomplish.

"We put everything we could to work and (US growth) is still just slightly better than 2 per cent That is some sign the tools did not have the potency we expect," Atlanta Fed President Dennis Lockhart told reporters following the US central bank's Sept 16-17 policy meeting.

While US unemployment rate halved to just over 5 percent from its recession peak in 2009, various studies estimate that quantitative easing could take credit for only between a quarter of a percentage point and 1.5 points of that decline.

The dramatic run-up in central banks' balance sheets also failed to bring inflation back to levels considered healthy, with the Fed far from its target and Japan and euro zone in or close to outright deflation.

In theory, ample and cheap money should encourage borrowing, spending and growth, but with households, businesses and governments scaling back debt after the crisis, major economies did not follow the script.

Less bang for those bucks

With a sense that there is little bang for the buck left in quantitative easing, the narrative is shifting from central bankers as superheroes to one of central bankers as bystanders, or, at best, in supporting roles.

"There are excessive expectations about what central banks can do," ECB vice president Vitor Constancio told Reuters in an interview. Europe's growth potential was weak due to a number of factors, including a shrinking labor market, and monetary policy was powerless in this respect, he said. "It is for other policy makers to do their job."

ECB chief economist Peter Praet also pointed out that lifting rates off the floor may be a challenge. "In some major economies, zero has featured for longer than any other value of the policy rate before," he told a conference. "The economy may have just gotten too used to that number."

Federal Reserve officials so far have stuck with the orthodox view that the world's largest economy can generate enough demand and investment to reach the Fed's inflation and employment targets, allowing them to coax interest rates higher regardless of the weak conditions elsewhere.

But the Fed's decision last month to delay a long-debated rate rise suggests doubt creeping in. One Fed member even called for "negative" interest rates - essentially taxing banks for holding excess reserves to make them put idle money to work.

A fringe idea perhaps, but a sign central banks could venture even deeper into the uncharted territory they entered with quantitative easing.

Bank of England chief economist Andrew Haldane in a recent speech said central bankers may need to accept that their good old days - of adjusting interest rates to boost employment or contain inflation - may be gone for good.

"That may require a rethink, a fairly fundamental one, of a number of current central bank practices," he said.

In a chronically low-growth world, central banks may have to break a final taboo and simply begin printing money to finance government spending, Steven Englander, Citi's managing director for foreign exchange, wrote in a recent paper.

"It directly injects purchasing power into the economy and will increase activity or inflation or both," he wrote, contrasting it with quantitative easing that comes with no guarantee that new money will lead to more spending.

Such policies, associated with past spells of runaway inflation, are anathema to central bankers and could prove unpalatable to those who already criticize the Fed and the ECB of overstepping their mandates with "quasi fiscal" measures.

Yet with governments either unable or unwilling to lead the pro-growth charge, the pressure on central banks is not going away any time soon.

"We are unavoidably and inexorably being led to the question: how do we get more growth?" Reserve Bank of Australia governor Glenn Stevens said recently. "Reasonable people get this. They also know, intuitively, that the kind of growth we want won't be delivered just by central bank adjustments."