Mr Modi’s vision of the state is neither too narrow nor too broad

Addressing a summit organised by The Economic Times on Friday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi -- for what may have been the first time -- outlined the broad socio-economic vision that underlies his government.

Addressing a summit organised by The Economic Times on Friday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi -- for what may have been the first time -- outlined the broad socio-economic vision that underlies his government.

This in itself was a welcome step. Indeed, he filled out his previous claims of ‘minimum government, maximum governance’ with a list of areas in which the state needed to work -- and implied that the government should no longer focus on issues outside those areas.

He made a case that his government had already begun carrying out major reform, but, as if to address the criticism that all the economic reform so far had been small-scale, stressed that small steps could nevertheless be impactful.

And he set to rest any ideas that his government would cut subsidies.

Subsidies would not end, he repeatedly insisted -- they would just be targeted better, with the leakages cut out.

But the goal of plugging leakages in the delivery of subsidies should not be underestimated.

The achievement of that goal will go a long way in helping the government contain the adverse impact of subsidies on its fiscal management.

Mr Modi’s delineation of the areas in which government needed to work was perhaps of most interest.

There were five, he said: public goods, such as defence and law and order; externalities, like pollution, where regulation was necessary; the control of monopolies; bridging information asymmetries and gaps; and the provision of welfare, as well as of education and healthcare.

There is nothing to quarrel with here; Mr Modi’s vision of the state is neither too narrow nor too broad.

The challenge will be to force the officials of his government to own this vision.

As he himself said: “In 20 years of liberalisation, we have not changed a command and control mindset.

“We think it is okay for the government to meddle in the working of firms.”

He did promise to rewrite the ‘DNA’ of the government, or laws, to make the working of the state more competent and efficient.

But there continues to be a misplaced faith in the existing human-resources structure of the government -- the true DNA of India’s government is not the laws, but the restrictive manner in which they are applied by control-seeking officials.

In general, Mr Modi pointed out that the end-process of development, as he sees it, is the creation of jobs: “Reforms, economic growth, progress — all are empty words if they do not translate into jobs.”

This is certainly true, and this is clearly what has underlined most of the initiatives of his government so far, particularly the manufacturing push entitled ‘Make in India’. However, the most important aspect of this push towards jobs was dismissed in a single sentence of a long speech -- skills.

The Skill India mission, Mr Modi said, would take care of that.

But it is far from clear how the Skill India mission is different from efforts made by the previous government, which failed to create enough work-ready young people.

Over 11 million young people join the workforce every year; a small fraction of those will find formal employment.

Many have been failed by their primary education itself -- the Annual State of Education Report found that barely a half of those in public secondary schools can do simple algebra.

Even those who have will receive no vocational education worth the name.

Mr Modi’s vision is welcome.

But it has a large and crucial gap and it is to be hoped that serious efforts would be made to plug it.

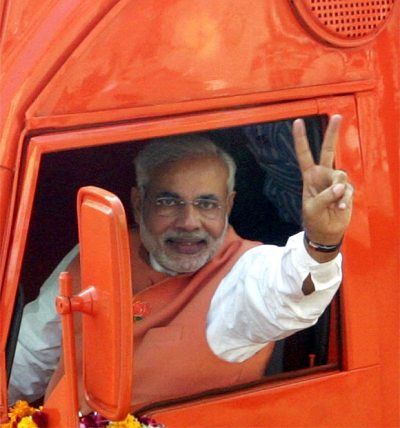

Image: Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Photograph: Reuters