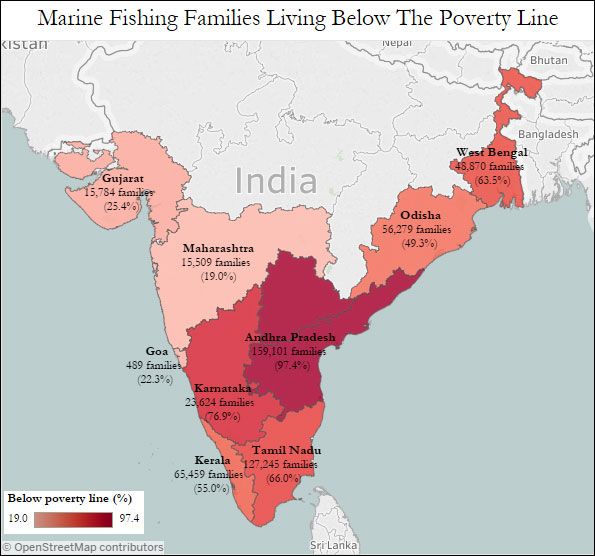

Distress sales, market closures and anchoring of fishing fleets have been reported from West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

A particular hammer blow appears to have been dealt by the new Rs 2,000 note because there is no change to return, reports Mukta Patil/IndiaSpend.

Gangu Kundaikar is a small-framed, sari-clad woman who rises at 3 am every day, wraps a cloth around her waist so the fish does not soil her sari, and takes a rented tempo to the Malim jetty in Panaji, North Goa, 8 km from her village, here in one of India’s most prosperous and literate states.

Kundaikar, 50, brings her day’s supply of fish back home to her village, Chimbel, where she sells them.

Kundaikar, who studied up to class 10, has no bank account and a phone without an internet connection. She is the only earner in her family of three, which includes her ageing mother and unemployed son.

Kundaikar bought fish worth Rs 3,000 to Rs 4,000 every day and kept the unsold catch in her refrigerator -- her only asset. She worked through most of the day and barely made enough to keep her family fed.

That was before midnight on November 8, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government scrapped 86 per cent of India’s bank notes, by value.

Since then, Kundaikar has struggled to balance her family’s budget: Demand for fish has fallen and sales have dropped by 30 per cent.

“We are poor, hard-working people,” she told IndiaSpend. “Because of this move by the government, it has become hard for us.”

After China, India is the world’s second-largest producer of fish, but it is a perishable commodity and less than 19 per cent of the fishing centres nationwide have infrastructure that allows fish to be processed or stored.

Less than 23 per cent of the fishing villages have internet access, and the fishing economy depends on cash.

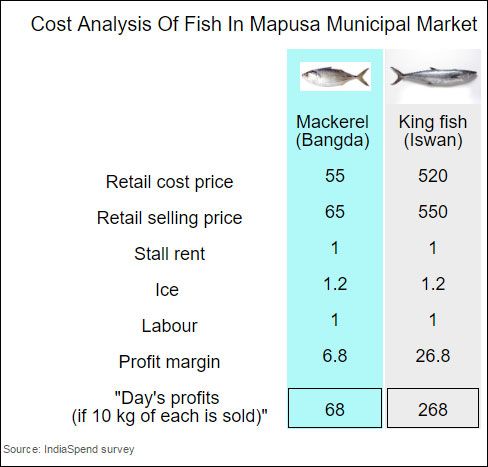

Profit margins vary according to the species sold, varying from 3.5 per cent (medium-priced fish) to about 10 per cent (high-priced fish) to 20 per cent (low-priced fish), according to this 2012 research paper.

So merchant charges by banks -- of 2-2.5 per cent (on credit cards), 0.75-1 per cent (on debit cards) -- and even the 1 per cent fee charged by Paytm, a digital wallet, is largely unaffordable, even if fishing villages had good internet access, which they usually do not.

With notebandi -- as the scrapping of the Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes is colloquially called --stories like Kundaikar’s have become common in fishing communities nationwide.

Distress sales, market closures and anchoring of fishing fleets have been reported from West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. A particular hammer blow appears to have been dealt by the new Rs 2,000 note because there is no change to return.

The crisis of 14.5 million Indians -- more than the population of Greece or Portugal -- dependent on fishing has crippled an industry that generates almost 1.1 per cent to India’s gross domestic product.

A quarter of these people work along 8,118 km of India’s coastline and 10 million along 197,024 km of inland waterways.

Most of these 14.5 million are part of India’s informal sector, unorganised workers, who constitute 82 per cent of India’s 500-million-strong workforce -- more than the combined populations of the USA, Germany and South Africa -- and generate half of the national GDP.

Their world, as we found, changed almost overnight.

Ground reality: Over 50 per cent loss in business, anger at government

Ground reality: Over 50% loss in business, anger at government

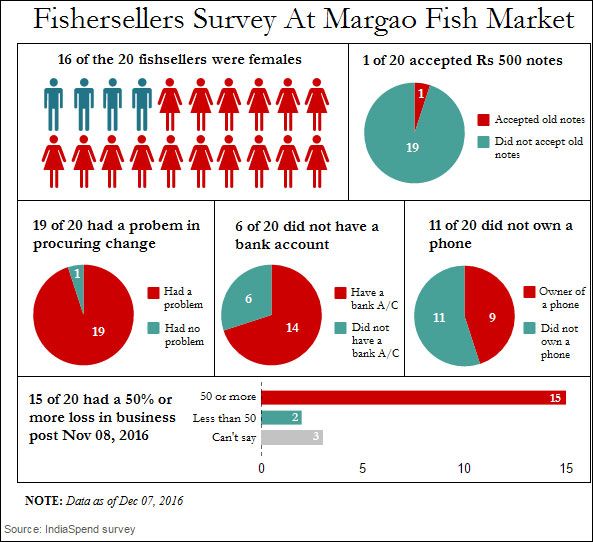

Of the 20 fish sellers that IndiaSpend surveyed at a government-run market in Margao, south Goa, more than 80 per cent reported buying less fish from wholesalers because demand was low, while 75 per cent reported income losses of half or more over the past month.

Our survey also showed that 30 per cent of the women did not have a bank account and that 55 per cent did not use phones. Of the ones that did, only 33 per cent had internet on their phone, which they did not use for banking.

Small-scale fish retailers earn between Rs 3,000 and Rs 4,000 every day, IndiaSpend found. If they were to use Paytm for transactions, they would be paying 1 per cent charge to withdraw their money, which is Rs 30-40.

For a daily profit of Rs 350-400, they said this is unaffordable.

Cashless transactions are not an immediate option, so the losses will continue.

In any case, most have no internet on their phone and hardly use their bank accounts, said Shashikala Govekar, president of the Fish Vendors Association at the Mapusa market.

We found a cascading effect of such losses.

Before November 8, fish sellers got Rs 280 to Rs 300 per kg of mackerel (bangda), which is now down by about 35 per cent to Rs 180 to Rs 200 per kg, according to members of the All Goa Wholesale Fish Market Association.

The Margao Wholesale Market is the only wholesale market in Goa, where catch from the neighbouring states of Maharashtra and Karnataka is also sold. Vehicles carrying fish from outside the state have fallen by a third.

Unless frozen, fresh fish must be thrown away if not sold within two days: 67 per cent of the fish consumed in India is fresh; no more than 23 per cent is processed (dried, frozen or canned).

Neither fish markets nor landing centres (harbours where fishermen land their craft) have cold storages.

Post-harvest fishing losses due to lack of infrastructure (for landing and berthing vessels) and domestic marketing are estimated to be as high as 20 per cent, according to a 2011 report of the erstwhile Planning Commission. These losses are exacerbated by the current market slump.

By 2012, less than 19 per cent of India’s fishing centres (256 of 1,376) were ‘developed’, which meant they had adequate landing and berthing infrastructure, and fish preservation and storage infrastructure.

There are onshore facilities for a third or less of India’s marine fishing vehicles, said the report.

With a large part of the industry informal and beyond the government’s purview, fisher folk are devising extra-legal ways to survive #Notebandi.

The case of the Rs 500 note: Still legal tender at fish stalls

By 11 am on a sunny day in Siolim, North Goa, half of Deepali Govekar’s sales were in Rs 500 notes, which are, of course, outlawed.

Govekar runs Dilip Sea Food, a makeshift stall supported by wood and crates that she rents for Rs 80 per day.

Govekar sold jumbo prawns, squid, red snapper, and Indian salmon (rawas) to James D’Souza, who buys fish here every day for his restaurant in Mandrem, North Goa.

“We are forced to give, and they are forced to take,” said D’Souza, referring to the seven Rs 500 old notes he had given Govekar.

“We have to take, otherwise the fish will rot,” Govekar said. “I will give them to the tempo that brought the fish as payment, and he can use it for diesel at the petrol pump.”

This circulation of notes from customers to retailers to wholesalers to transporters/ trawlers was underway until December 2 -- the last day that petrol pumps were accepting old notes.

Small-time fish sellers who had bank accounts were accepting Rs 500 notes even after December 2 and were depositing them because no one outside the fish market was accepting them.

If they refused these notes, they lost out on customers and were left with rotten fish the next day, because they had no change for the new Rs 2,000 note.

All but one of the 20 retailers we surveyed at the Margao market said they did not have change for customers, and this was why they were accepting Rs 500 notes, as of December 7.

“Why did the government not introduce the new Rs 500 note first?” asked a Margao fish seller who requested anonymity. “This difference between the Rs 100 and the Rs 2,000 note is too large. Our business is suffering terribly.”

Can Goa really go cashless?

A major reason that India is unprepared for a cashless economy is a lack of connectivity.

At least 73 per cent per cent of Indians (912 million people) do not have access to the internet, IndiaSpend reported on December 3.

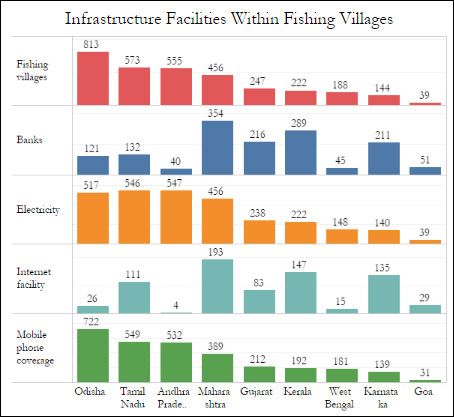

Within 3,237 marine fishing villages in nine of India’s coastal states, 91 per cent villages have mobile phone coverage, but barely 23 per cent have access to the internet.

Fishing is predominantly a cash-based economy.

The diesel used for trawlers and transport, renting of stall space at markets, labour and buying ice, and payment for fish (whether by retailers or customers) is done with cash or taken on credit.

Ashok Lamane, who sells fish to several restaurants near Morjim, said the credit component of his transactions increased manifold since November 8. “I am owed at least Rs 1,80,000 by the restaurants and, in turn, I owe money to the trawler owners,” he said.

At the Margao wholesale market, the use of credit is rising.

“Earlier, too, the market worked on credit -- around 50 per cent of all transactions – but now, this has increased to 80 per cent,” said Sridhar Pujari, a wholesaler. “And while earlier, the payments would come in two to three days, now it is taking people eight to 10 days to return the cash.”

Pujari pays for fish stock by cheque, but said it is “impossible” for the business to go cashless.

One reason is the nature of the business itself. Since fish does not last long, retailers buy on credit and then repay wholesalers after they have sold their stock.

Another reason is that daily wage labourers, such as fish cleaners, ice carriers and crate carriers, don’t have bank accounts and want to be paid daily in cash.

Back in Mapusa, Shashikala Govekar -- she has no internet on her phone, and has not used her ATM card despite having one -- offered her response to Modi’s cashless urgings.

“Seventy per cent of people dealing with fish, whether wholesale or retail, are illiterate,” she said. “We don’t even know how to use smart phones, how will we operate swipe machines?

“We make a profit maybe once in four days and have 12 other kinds of trouble without having to add these machines to the list.

“Besides, the wholesale markets run from 3 am to 6 am, and it is dark. While handling fish, how will we swipe and sell?”

Mukta Patil is an analyst with IndiaSpend.

Powered by  Indiaspend.org is a data-driven, public-interest journalism non-profit

Indiaspend.org is a data-driven, public-interest journalism non-profit