Soon after the BJP lost the 2004 election, the stockmarkets went into unprecedented free fall.

Then SEBI Chairman G N Bajpai reveals how his firm handling of the situation restored confidence and soon the markets were back to doing what they do best -- make money.

A revealing excerpt from his book, A Game Changer's Memoir.

The results of the May 2004 general election came as a rude shock to many.

Capital market investors expected the NDA to come to power.

Thursday, 13 May, the Congress emerged as the single largest party in the Lok Sabha.

Investors perceived this as a negative development, believing that the economic reforms would be consigned to cold storage by the new government.

The stock markets, understandably, reacted negatively that day.

14 May 2004 happened to be a Friday. The BSE Sensex and NSE Nifty closed approximately 6 per cent and 8 per cent, respectively, below their previous day's close.

The dip was significant, but panic was nowhere in sight; neither had the threshold for applying marketwide circuit breakers been hit, either for the Sensex or the Nifty.

The weekend was characterized by trademark calm before the impending storm, which hit on Monday, 17 May 2004.

That day, the markets woke up to a tsunami, blowing everyone away.

In a matter of just three hours, the Sensex and Nifty suffered intra-day falls of 842 points (approximately 17 per cent) and 290 points (approximately 18 per cent), respectively, from their previous day's close.

The first circuit breaker was applied when the indices fell 10 per cent, and the markets were shut for an hour, as per SEBI's prescribed risk management system.

When the markets reopened after an hour, the situation further deteriorated, and the Sensex fell by another 7 per cent, roughly, and the Nifty by another 8 per cent, approximately.

Circuit breakers were applied again, and all exchanges suspended trading once more, this time for two hours!

All this happened in a matter of hours of the market opening bell going off, and crores of rupees of investor wealth was wiped out!

To put it in perspective, this was the worst ever intra-day fall in the entire history of Indian stock markets until that day.

SEBI was dragged into this for failing to take timely action and allowing markets to go into a free fall at the risk of investor money.

They all demanded that some corrective action be taken, either by the government or by SEBI, to restore market stability at the earliest.

Amidst this intense drama, there was one thing everyone wanted to know -- what is SEBI doing and where is the SEBI chairman?

As destiny would have it, I was about 4,000 km away from India.

IOSCO (International Organization of Securities Commission) had scheduled its annual general meeting in Jordan, coincidentally, for Monday -- 17 May 2004 -- and I was required to represent SEBI.

On the fateful Monday morning at Amman, as I was getting ready to attend the IOSCO meeting, I felt I should check the television to see if everything back home was fine, purely out of curiosity.

Since Jordan is 2.5 hours behind India, the markets in India had already opened.

Switching on the TV, I saw both the Sensex and Nifty melting.

They had already nosedived more than 10 per cent down from their previous close.

The circuit breaker had been applied.

After some time the second circuit breaker was applied.

I stood there completely numb, watching the bloodshed in horror.

In between, I got a call from my wife Asha who asked me in a worried voice, 'Where are you? Everyone is accusing you of running away!'

I assured her that everything would be fine, although I was myself very uncertain that it indeed would be so.

I was extremely disturbed and lost all interest in the meeting for which I had come all the way.

I decided to return to Mumbai without attending the meeting at all.

But even before we had boarded the flight back, I was receiving frantic calls from India to take the all-important decision, and almost in real time.

Trading having been suspended at the exchanges for the second time, the BSE and NSE had been shut for more than two hours, and as per the rules prescribed by SEBI.

They had to be opened for trading again, once the stipulated third hour was over.

But no one was willing to take the decision to open them again, for fear of a further fall in the market indices.

That would mean failure of settlement and sound the death knell for market participants.

After all, the sell-to-buy ratio just before trading was suspended was at a mind-boggling 24:1.

Ultimately, it fell on me to decide whether we were going to strictly follow the rules and resume trading or go by the general sentiment and close trading for the day.

I had about thirty minutes to make up my mind. The fate of our investor community rested on my shoulders!

Everybody whom I spoke to, except Ravi Narain, MD and CEO of NSE, were of the view that the markets should remain closed for the day, fearing further mayhem.

Everybody warned me to close trading, but the responsibility of the final decision fell to me alone.

I attended all the calls (while in Jordan) and heard everyone out.

I knew the easiest and safest route was to just keep trading suspended for the remainder of the day.

I had enough explanations to back this decision, in case any questions were asked later.

But I was still unsure of what to do, since a few contrarian arguments were running in my head too.

I started weighing the consequences of keeping the market open. Now I had just about twenty minutes left to make my decision.

First, I felt that investors were misreading the situation, and hence overreacting to it.

While it was true that the left parties would, in all likelihood, be partners in the ruling coalition, the government would actually be led by the Congress, and the PM was going to be Dr Manmohan Singh.

After the initial hullaballoo, I felt the markets would be able to see some merit in Singh's appointment as PM and see that the original reformers would not let the spate of economic reforms die down.

Second, the economic fundamentals seemed strong.

The Indian economy was on the upswing, with GDP growth at levels of over 8 per cent.

Our constant vigil had ensured that, unlike during boom prior to 1992 or Scam 2001, there was no froth in the market.

Being an ex-LIC chairman, I knew there was a strong possibility that, in such a scenario, long-term investing organisations like LIC would very well pursue a contrarian path and buy when the markets were crashing.

I felt there could be others too who would, similarly, have the sense to go against the frenzy and find low stock prices a ripe opportunity to invest (what is called 'buying on dips').

Further, even if the ratio of sell to buy improved from 24:1 to 12:1, the markets would stabilise, if not go up.

Third, the rules prescribed during my regime entailed opening of the markets after the second circuit breaker and to close them for the day only if they fell by a further 5 per cent.

Closing the market after the second circuit breaker would mean changing our own rules.

I had a very strong instinct that the markets would stabilize if investors were allowed to trade again.

Even if the markets opened the next day, I realised, there was no guarantee they would revive. Hence the risk was inherent in either decision.

But if I opened the markets and if stability returned (which my gut was telling me would happen), then it would turn out to be good for the nation in many ways.

To begin with, investors would have some respite from their anxieties. The settlement would be smooth.

The SEBI rules, of keeping the markets open for trading after a cooling off period under market-wide circuit breakers, would be respected.

This would reaffirm the robustness of SEBI's risk management framework.

If the markets stabilised now, they would come across as naturally resilient, and as having the ability to bounce back on their own.

With all this pondering, I became all the more certain to let trading be opened and allow the market participants decide their fate themselves.

I had done my calculations and was willing to take that risk of backing my instincts to allow the markets to open again.

With that thought, I took a two-minute breather, drank a glass of water to soothe myself, prayed to my gods and, against the advice of most of the well-wishers who had called, decided to follow the rule book.

The markets opened.

As they say, the rest is history.

It was indeed astounding how the markets rose, like a phoenix from the ashes, from their once-in-a-lifetime depths to finally settle at approximately 11 per cent (565 points) and 12 per cent respectively, by the end of the day.

The markets shot up by approximately 6 per cent from their lows, relieving many tensed nerves, and my stand of allowing the markets to open was finally proven right.

Today, though, people seem to have forgotten that such a nerve-wrecking decision had to be taken in a few minutes and that this resulted in the markets springing up from the unbelievably low depths they had fallen to.

We reached Mumbai well past lunch time the next day.

We took stock of the situation and immediately began interactions with the chiefs of the stock exchanges and the SEBI teams.

Our focus now was to ensure that on the next day settlement happened smoothly and our risk management processes worked.

The SEBI team quickly analysed broker positions, the margins they had and the extended RBI line of credit.

Overnight, we called tens of brokers who had large positions to confirm that they were confident of honouring their deals and settling smoothly the next day.

Our proactive actions yielded fruit, and next day the settlement of all trades happened smoothly. We heaved a sigh of relief!

The most noteworthy precedent established by these events was to trust the market to get up on its feet; to keep the ground rules robust; and watch from the ringside that the game was played fairly.

Having laid the firm foundations, the referees -- the regulators -- should zealously guard the sanctity of the ground rules and reassess the solidity of the bricks of the plinth to ascertain that they are worthy of the faith that markets would bounce back on their own.

This sets a benchmark for the action to be taken during future falls.

Even after the markets had revived, there was clamour from various political quarters for my resignation.

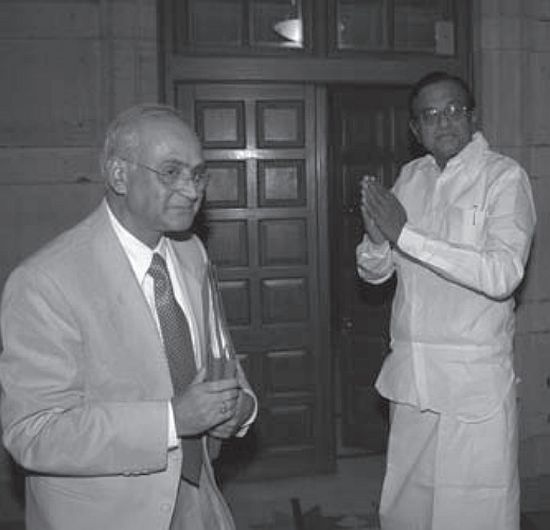

After a couple of days I went to meet the newly appointed finance minister, P Chidambaram, and at the end of our conversation I offered to quit.

But Chidambaram graciously replied, 'Why do you even say so? Why think about it until I ask you to?'

As I was leaving, against his usual practice, Chidambaram came up to the entrance of his office and opened the door to see me off.

There were quite a few media people waiting there and Chidambaram's gesture of seeing me off at the door blew over the speculation about my quitting, giving the media the message that I enjoyed the minister's confidence.

In the end, the episode turned out to be an immensely gratifying experience for me.

The regulatory body's faith in the investors' intelligence to read the situation correctly, and in its systems and processes, checks and balances, the efficacy of ground rules, had emerged victorious.

The calculated bet I had taken had paid off.

It reaffirmed my belief in the power of thinking with a cool head when everyone around is panicking.

Excerpted from A Game Changer's Memoir: EX-SEBI Chief Recounts The Defining Moments Of His Tenure by G N Bajpai with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House India.