A hurried reform agenda will be either too squeamish or too ambitious and impractical, says Andy Mukherjee

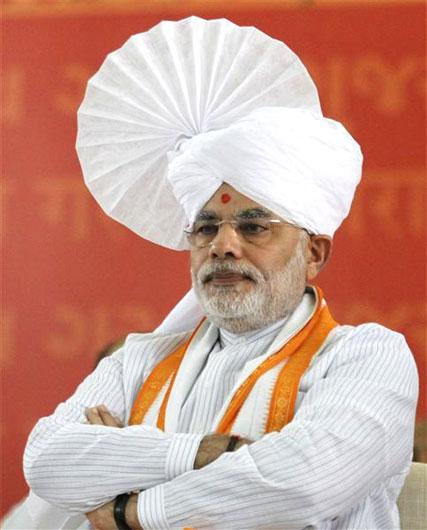

Narendra Modi should think small during 2014. If the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) does win next year’s general election in India – as political pundits increasingly believe it will – the future prime minister should resist the temptation to immediately unveil a grand economic strategy. In the interim, he should focus on quick and effective repair jobs in the banking, electricity and textile sectors.

Such a limited agenda sounds counterintuitive. Indians are impatient for an end to the double whammy of economic stagnation and high inflation. Financial markets are already pricing in a victory for Mr Modi. Moreover, resistance to unpopular decisions is usually at its lowest when politicians are still enjoying the first flush of victory.

But a dose of realism is needed. By the time Mr Modi and his Cabinet are ready for business, the first quarter of India’s next financial year will be over. A hurried reform agenda will be either too squeamish or too ambitious and impractical. In either case, investors will end up disappointed.

The Union Budget in February 2015 will be the first real opportunity for Mr Modi’s finance minister to present a well-conceived strategy for economic reconstruction. In the meantime, the new government should focus on repair work — the kind that will pay quick dividends but won’t require messy legislation.

Three tasks that can help build investor confidence and prepare the ground for deeper reforms stand out: recapitalising banks, giving more electricity to villages and increasing the interest rate subsidy for textile industry loans.

Click on NEXT for more...

A bold recapitalisation of government-run banks will revive stalled credit flow. Indian banks rated by Moody’s Investors Service could need up to $6 billion (Rs 36,000 crore) in fresh capital next year.

Most of the shortfall will be in state-run lenders. At two per cent of the federal government’s annual expenditure, recapitalisation will be an expensive proposition, but not prohibitively so.

Just the top 11 state-owned banks have received $7 billion from the government over the past four years. Besides, since shares in many of these banks are changing hands for less than their book value, a recovery in credit will see the government make a paper profit on its investment once the bad loan problem eases.

In exchange for writing the cheque, though, Mr Modi should insist on merging the 26 state lenders into, say, 10 larger, better-managed banks over time.

When Palaniappan Chidambaram, the current finance minister, mooted the idea of consolidation eight years ago, about one million bank workers protested. But the lenders’ woeful finances present an opportunity for Mr Modi to restart the project.

The new government doesn’t need to immediately embark on a privatisation drive — although that is where consolidation will eventually lead once there’s political appetite for it.

Click on NEXT for more...

Another of Mr Modi’s immediate repair jobs should be to contain rampant losses in the power sector. India’s power distribution utilities lose 1.5 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) annually. That’s partly because of theft.

But mostly, it’s because of farmers. They guzzle power but hardly pay anything for it. The state-owned distribution utilities lose money and cannot repay working capital loans to state-run banks. Last year, the government had to step in and restructure $35 billion (Rs 2 lakh crore) of the utilities’ debts.

The distribution companies’ attempts to manage the problem make it worse. They provide very little electricity to villages, and enforce debilitating power cuts in cities. This crushes productivity.

A permanent solution is perhaps still many years away. But a good interim fix will be to separate the feeder cables that supply electricity to farms for irrigation from those that carry it to the rest of the village.

Click on NEXT for more...

A World Bank study of a small area in Mr Modi’s home state of Gujarat where such separation of lines has been implemented showed a 22 per cent jump in villagers’ real incomes, compared with a smaller 13 per cent escalation in their real energy expenses.

The distribution company still may have to supply as much free or nearly free power for irrigation as before, but it benefits by recouping the full cost of electricity from village households and small industries.

Healthier distribution companies will increase the attractiveness of India’s power business to investors. India’s infrastructure for generating, transmitting and distributing electricity will need $1 trillion (Rs 61 lakh crore) in investment over 20 years, according to consulting firm Bain.

The solution is also easy to execute. The per-kilometre cost of separate cables is about $4,000 (Rs 2.4 lakh). Rather than dangle the carrot of federal assistance to states that commit to lowering their power distribution losses, Mr Modi should make an immediate, non-conditional grant to cover the expense. Productivity gains alone will pay for the investment in a short period.

Click on NEXT for more...

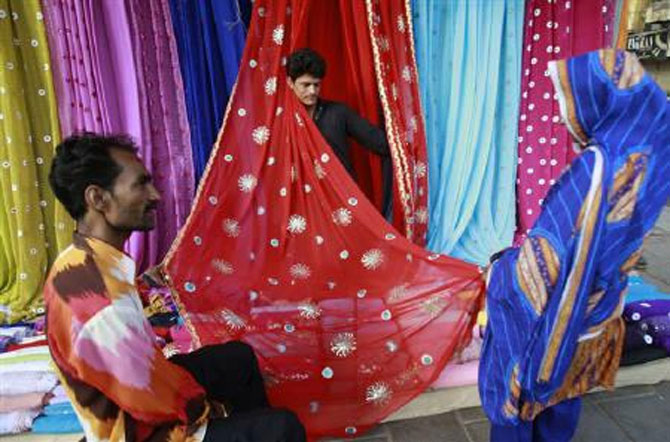

Raising productivity in the textile industry will be harder. India is the world’s second-largest cotton producer after China. But while China imports cotton to make clothes for the world, India will this year export about one-fourth of its production. This should alarm Mr Modi. After all, the country could create more jobs by turning cotton into fabric and garments for exports.

But unlike its rivals in Bangladesh and Pakistan, the Indian textile industry doesn’t enjoy much preferential access to developed countries. Besides, the current government has massively increased guaranteed minimum prices for cotton farmers, crimping manufacturers’ profitability.

The government has offered some help: textile manufacturers enjoy a three percentage point interest subsidy on export credit. However, Mr Modi should increase it to five per cent for five years. That might seem like making an industry that’s beginning to benefit from a weaker rupee more dependent on handouts.

But it’s better to give money to companies that can create hundreds of thousands of new jobs than waste it on subsidising cereal consumption in a nation where the real nutritional shortage is in protein.

These three quick fixes do not amount to a manifesto for the government. Solving India’s problems will require a much more ambitious long-term programme. But if Mr Modi can make some swift improvements immediately after winning the election, his government will be in better shape to tackle the many bigger challenges ahead.

The writer is the Asia economics columnist at Reuters Breakingviews in Singapore. These views are his own