Photographs: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters Tony Munroe and Suvashree Dey Choudhury

Government incentives to grow rice and wheat as part of a subsidised food programme for the poor also keep prices high.

The biggest overhaul of India's monetary policy in 15 years aims to tackle the nagging inflation that pushes up credit costs and stifles investment, but the changes risk imperilling already weak economic growth in the absence of broader reforms.

A Reserve Bank of India (RBI) panel recommended sweeping changes to how the central bank runs policy, including setting a long-term inflation target of 4 percent, with wiggle room of 2 percent in either direction.

Critics say the ideas would bring a western-style rigour to an economy with emerging market problems; supply bottlenecks, unpredictable monsoon rains and politically sensitive subsidy spending that drives up food prices.

Monetary decisions would be set by a committee - they are now made by the governor - putting the RBI in line with the practice at most major central banks.

The arrangement, described by Standard Chartered Bank in India as "one of the most important steps" in at least the last 15 years, may not suit India, some argue.

"I think we need to have a strong decision-maker at this stage given the peculiarities of the macro-economic situation," said Abheek Barua, chief economist at HDFC Bank.

"And I think this kind of aping of some of the western central banks does us no good. There are huge constraints on the supply side," he said.

Click on NEXT for more...

Rigour and risk in RBI's reform push

Photographs: Reuters

One of the biggest sources of inflation pressure in India is a bottleneck in food production and distribution. One-third of fresh food perishes before it reaches shops and unpredictable weather often adds to supply pressures. That helps explain why consumer prices are rising around 10 percent over year-earlier levels.

"Inflation targeting is done in countries which have more stable kind of pricing," Economic Affairs Secretary Arvind Mayaram said in an interview with the ETNow TV channel.

Government incentives to grow rice and wheat as part of a subsidised food programme for the poor also keep prices high. Another cost pressure is widespread pilfering in government food schemes.

Reducing 10 percent consumer inflation to 4 percent would require politically difficult moves to curtail food prices that have been rising by double-digits for years.

"Even if inflation is higher, it does not mean that people will start eating less just because the interest rates are higher," Mayaram said.

"There are other structural issues that need to be addressed if we need to control food inflation," the official said, adding that the panel's proposal to use consumer prices to anchor inflation was "a little premature".

The current CPI measure was launched in 2012.

Click on NEXT for more...

Rigour and risk in RBI's reform push

Photographs: Rupak De Chowdhury/Reuters

Short-term pain

While switching to the CPI as the key inflation measure would put the RBI in sync with most central banks, it would also mean current policy interest rates of 7.75 percent would likely remain high, a prospect that pushed up government bond yields by 10 basis points on Wednesday.

"These recommendations clearly carry hawkish implications," wrote Credit Suisse economist Robert Prior-Wandesforde.

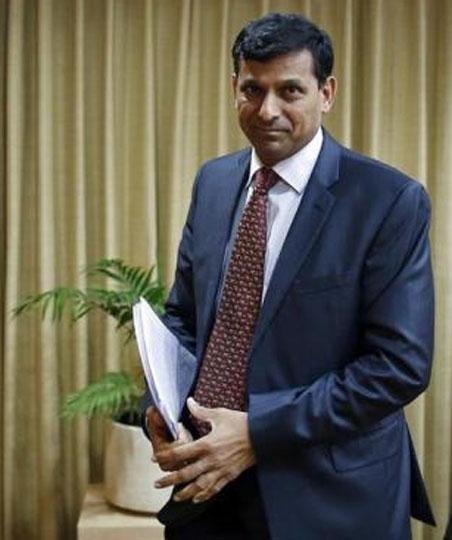

Under the recommendations of the panel, set up by RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan, managing inflation would be made the primary policy goal of the RBI, ahead of growth and financial stability.

While some of the recommendations announced Tuesday would need legislative approval, most could be implemented by the central bank.

Rajan, a high-profile former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund who took office on September 4 in the midst of a currency crisis, has in the past spoken in favour of setting monetary policy by committee and establishing an inflation target using the CPI.

Click on NEXT for more...

Rigour and risk in RBI's reform push

Photographs: Pawan Kumar/Reuters

Ready or not?

The government of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has struggled to implement reforms or remove bureaucratic hurdles that would attract investment to ease the country's inherent inflation pressures.

A 2012 decision to allow entry to foreign supermarkets, intended to reduce widespread wastage due to a lack of facilities such as refrigeration, has generated little interest because of stiff local sourcing requirements. The UK's Tesco Plc recently became the first such chain to invest, albeit with a relatively modest $110 million commitment.

Singh's government has been paralysed by corruption scandals that have stifled reform efforts. It faces an election by May, the outcome of which is uncertain.

"The question is whether there is political support for bringing down inflation. If the new government undertakes reforms to reduce subsidies and bring down food inflation, the headline CPI inflation can come down fast," said A Prasanna, economist at ICICI Securities Primary Dealership.

The RBI's current mixed mandate of managing inflation, economic growth and financial stability all in one gives it flexibility but has also led to often-shifting priorities. Critics say that has stifled growth - Asia's third-largest economy is expanding at its slowest pace in a decade - without bringing inflation under control.

"It's a big positive for India's macro policy framework if they can get this implemented, because it will basically help I think better anchor monetary policy by establishing a clear objective," said HSBC economist Leif Eskesen, echoing the sentiments of many economists.

Click on NEXT for more...

Rigour and risk in RBI's reform push

Image: Raghuram Rajan (left), with former governor D Subbarao at RBI's headquarters in Mumbai.Photographs: Reuters

The challenge is fitting rigid inflation management into an often-messy political reality.

Rajan's predecessor at the RBI, Duvvuri Subbarao, repeatedly called on New Delhi to implement reforms to ease investment rules, clear infrastructure bottlenecks and cut government subsidies, but with little success.

The new policy set-up would raise the stakes for the government to act - a tall order, especially if another fragmented coalition emerges from the upcoming elections.

Governments have tended towards promoting growth and putting pressure on the RBI to keep monetary policy loose. The Mumbai-based central bank is not technically independent - the governor and his deputies are appointed by the government - although it generally enjoys latitude in policymaking.

Setting a CPI target of 4 percent over the long-term would remove some of the discretion in policymaking and at the same time strengthen the central bank's independence by insulating it from pressures from New Delhi.

article