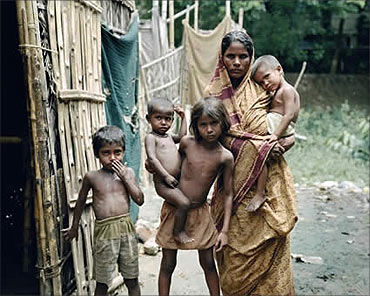

Photographs: Reuters Rajni Bakshi

Cash or food, which will better benefit the poor? This deceptively simple looking question is currently at the centre of a sharply bitter dispute.

Combatants agree that the poor must be helped. But both sides fling ugly allegations about the 'others' actually locking people into poverty.

On the surface this is a contest between some members of the National Advisory Council (NAC), who are deemed to have socialist leanings, and those who favour free-markets.

On closer examination you will find a more multi-dimensional puzzle.

While the immediate dilemma over cash versus food dilemma is relevant and urgent -- it is also a decoy. Such heat and fury about how to feed the poorest of the poor takes attention away from the core question: what will make, both, the society and the market work for everyone?

. . .

Cash or food? A great transition for India

Photographs: Reuters

This question cannot fully be explored by those who are locked into either a pro or anti-liberalisation stance.

It is painfully ironic that a large number of Indians are still struggling for basic needs even 20 years after India shifted towards a more market-oriented economy. But this is not sufficient reason to reject the role of markets in human well-being.

That would be dangerously simplistic. However, it is equally untenable to argue that somehow making markets more 'inclusive' will make all Indians prosperous. This approach is delusional.

There is a tendency to look for a happy middle-ground between these two extremes. But that locks us into two corners of the same box. What is needed is fresh thinking and action based on a nuanced perception of reality in all its multiple shades.

Interestingly, the Indian controversy over its Public Distribution System (PDS) coincides with two anniversaries which are largely being ignored here.

. . .

Cash or food? A great transition for India

Photographs: Reuters

This is the birth centenary year of E F Schumacher, author of the famous book Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. Plus the London based New Economics Foundation (NEF), which has done pioneering work to advance Schumacher's insights, is celebrating its 25th anniversary this month.

Why is this relevant for us here in India? Firstly, because there is urgent need to look closely at creative challenges to conventional economics. And secondly, because NEF is a good example of how seemingly radical ideas can be brought from the fringes and made mainstream.

In 1984 social and political activists from across the world met for the first time for The Other Economic Summit (TOES), as a counter-point to the G8 Summit.

TOES went on to become a platform which drew on diverse experiences to show how the conventional map of economic growth was out of synch with reality.

Globally, wealth generation is happening at enormous cost to the environment and to large segments of the population in many countries.

. . .

Cash or food? A great transition for India

Photographs: Reuters

The NEF was initially meant to serve just as a secretariat for the annual gatherings of TOES. It went on to become one of the United Kingdom's biggest think-tanks -- one dedicated to transforming the economic system.

That means creating 'new economics that maximises well being and social justice within the limits of the planet'.

Twenty five years ago the attention of activists who gathered at TOES was on five major shifts -- alternative economic indicators, green taxation, social auditing, local money flows and local currencies.

In the Western countries the first four of these ideas are now considered mainstream. Among other things NEF has done extensive work on how public policies and market forces are disadvantaging local economies in many parts of the world.

It coined the term 'clone towns' to capture how the spread of large retail chains across the UK has damaged local businesses and made all towns look the same.

. . .

Cash or food? A great transition for India

Photographs: Reuters

The NEF takes credit for the launching of UK's Well-being Index and the establishment of the Green Investment Bank. Its Happy Planet Index has been downloaded by a million people across the world.

Since the financial meltdown of 2008 the NEF has launched a Great Transition initiative which it describes as a 'hugely ambitious project to build both a new model of the economy to guide the transition to a sustainable future and a collaborative campaign to make it happen'.

Many of the specific ideas and mechanisms that NEF has crafted do have a greater application in the Western economies. But its basic emphasis on well-being, rather than just production and transactions, as the measure of 'growth' has universal application.

We need to ask what unique form a Great Transition might take in India. How will local economies, from village and small urban areas to larger towns, become more dynamic?

What forms of skill enhancement along with access to natural resources will benefit everyone? There are no readymade or easy answers to these questions.

But the good news is that both disputants in the cash versus food dispute have a deep interest in looking for answers, some are actually doing it on the ground.

Nevertheless, and this is the bad news, much energy is being expended in exchanging accusations about who is more pro-poor.

article