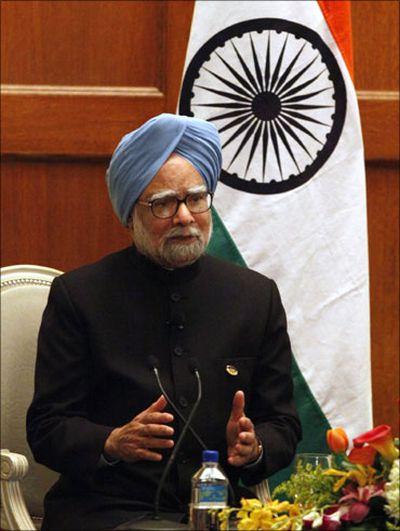

On the cusp of the general elections this summer, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh posed a set of questions to the Planning Commission he had headed for 10 years.

"Are we still using tools and approaches designed for a different era?" Singh asked, wondering if the body needed to take on additional roles, like improving governance, to remain relevant to the growth process.

The answers came too late. On May 29, three days after Narendra Modi was sworn in as Singh's successor, the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) - an ombudsman attached to the Commission - gave a 12-page report recommending "the Planning Commission be abolished and its staff returned to their parent cadres."

...

Last week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the Commission would be replaced by a "new institution", with a "new body and soul and with new direction".

The PM's Office (PMO) has since invited public comments on the possible form of the successor. Yet, opinion is divided if a new entity could avoid the pitfalls of its predecessor.

The questions are twofold. What will succeed the 63-year-old organisation?

And, is the abolition of the Commission the end of the five-year plan, the most visible manifestation of the Indian government's intervention in the national economy?

Montek's point

In an interview with this newspaper in May, the Commission's former deputy chairman, Montek Singh Ahluwalia, said its many roles could not be wished away.

The Commission, he noted, allocated plan resources, appraised programmes and evaluated policy, all the while balancing the financial needs of the states with the abilities of the Centre.

...

"If you abolish this body, you would have to assign these tasks to some other body," he said, "This would make it very like the Planning Commission."

The current plan - the 12th since the Commission was set up in 1951 - runs till 2017 but is due for mid-appraisal later this year.

"The 12th plan is premised on eight per cent annual GDP (gross domestic product) growth, while the Jaitley Budget is premised on unusually high tax collections," said an official, "Neither of these targets are likely to be met, so the current plan would have be substantially revised."

IEO

So, who would carry out this revision or abandonment of the 12th Plan, and who will guide Centre-state relations in the post-Commission future?

The IEO report offers the only publicly available template for the Commission's successor:

The Commission's roles are split into three, with the Finance Commission (FC) taking on the responsibility of allocating centrally collected funds between states and the Centre, funds between various central ministries will be distributed by a specially created department of planning within the finance ministry, and a think-tank will provide the government with policy guidance.

...

"The great heyday of centralised planning ended with the third plan [1961-66]," said economist Bibek Debroy, who has been linked to the new entity in media reports, a speculation he denies, "Today, most resource allocation is done by the private sector."

Debroy said he was broadly in favour of the abolition of the Commission but was keen to see what replaced it.

Budget data suggest that, over the past two decades, total central funds routed through the Commission to the states varied between 3.5 and five per cent of GDP (see box).

The FC could handle this money, as it already allocates central tax revenues. Further, the FC is a constitutionally mandated body, answerable to Parliament, unlike its Planning counterpart - which was created by, and is answerable to, the PMO.

...

"But the FC has a very narrow technical focus, unlike the Planning Commission which has a broader developmental approach," said economist Abhijit Sen, who was a member of the earlier Planning Commission and is a sitting member of the FC. "The FC is a small organisation, with limited capabilities."

Meanwhile, the IEO model suggests, the finance ministry could allocate money between central government departments.

Debroy said the finance ministry in any administration is under pressure to reduce budgetary deficits.

"They tend to slash social sector expenditure and capital expenditure," he said, "You need a counterweight like the Planning Commission to make a case for social sector expenditure."

The think-tank could do that, but the problem is, Sen said, "No one listens to a think-tank unless it has some powers."

In the Planning Commission's case, it had the power to delay disbursal of funds for central schemes by insisting states follow programme guidelines, which probably proved to be its undoing.

...

How to balance?

In June 2013, Modi arrived at Room 122 of the Planning Commission in his capacity as Gujarat chief minister.

In his presentation, he expressed his disapproval of central legislation like the Right to Education Act that imposed financial liabilities on the states by demanding state funds to match central grants.

"As a result," the presentation noted, "the states are required to alter their own development priorities and set aside funds to meet the liabilities created by the central legislation."

Modi's comments have been echoed by many CMs over the years.

Economists like Arvind Panagariya have called for the end of central schemes in favour of block grants, to allow states to choose their development priorities.

Central plans, the argument goes, ignore the differing development stages and capacities of India's diverse states. Without central schemes, there shall be no need for a commission to plan, design or evaluate them.

"The CSS (centrally sponsored schemes) were evolved precisely to incentivise the states to spend more in critical areas," former deputy chairman Ahluwalia said in his May interview with Business Standard, even as he said the Commission was moving to make the process more flexible and less cumbersome.

"But a key issue is that we were not doing old-fashioned central planning anyway," he said in an email this week.