Photographs: Courtesy, Outlook Business Krishna Gopalan, Outlook Business

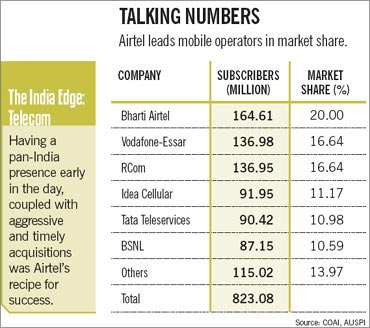

When Vodafone dialled into India in early 2007, it was the biggest foreign direct investment in India, acquiring a little over half of Hutchison's Indian telecom assets for almost $11 billion.

India was one of the few growing telecom markets globally. For Vodafone, the world's largest telecom company with a presence in 27 countries, presence here was an imperative, not an option.

For its price, Vodafone got a subscriber base of 24.4 million across 16 cellular circles. By comparison, market leader Bharti Airtel had over 33 million users with a pan-India presence (operations across 23 cellular circles).

What was perhaps galling for Vodafone was that Bharti and Hutch had entered India around the same time, although Bharti had quickly taken a lead in subscriber numbers. When Vodafone bought Hutch, that gap continued and has only widened since.

A former Hutch executive recalls the decision taken at the Hong Kong headquarters to focus on large and lucrative circles and be positioned as a premium brand. "That was a big mistake strategically and Bharti just moved ahead," he says.

Today, Vodafone has 137 million subscribers, while Bharti has 165 million.

. . .

Outlook Business, June 25, 2011

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Courtesy, Outlook Business

But this isn't a story about Vodafone and Bharti. Not entirely.

It has become part of business lore now how a sleepy elephant has metamorphosed into a hungry tiger since 1991. What's less talked about is just how much effort it took for India to make the transformation from a protected, closed economy to one that was in step with global developments.

Indian companies that fell short on technological prowess or the ability to integrate with a global play quickly fell by the wayside. But several also emerged winners in face-offs with large multinationals.

Some of them either fortified the old guard or created new giants. If the Tatas and Birlas went from strength to strength, the emergence of Bharti and Infosys were equally important.

And together, these companies have given multinationals a run for their money across sectors. Sure, foreign-origin companies may still hold sway over consumer product and electronics companies but, in several areas, be it tractors, liquor or specialised financial products, it is the Indians who are the kings.

Not just another market

Consider Lafarge, one of the world's largest cement companies. The Paris-headquartered major entered India after buying Tata Steel's 1.8 million tone (mt) cement business in 1998, which was followed soon by the acquisition of Raymond's 2.2 mt plant.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Reuters

Together, the two deals cost the company over Rs 1,300 crore (Rs 13 billion) and gave it a capacity of 4 mt at a time when India's total cement manufacturing capacity was 120 mt.

Ten years on, India's total capacity has more than doubled to 270 mt, while Lafarge accounts for 6.5 mt -- its share has dropped from 3.3 per cent to less than 2.4 per cent.

All global cement giants, including Holcim, Heidelberg and Italcementi, have a presence here. Dalmia Bharat Enterprises managing director Puneet Dalmia points to the size of the Indian market to explain why.

India is the second-largest cement manufacturer in the world, ahead of the United States (100 mt) and Japan (50 mt) and behind only China (1.5 billion tonnes per annum).

"The long term demand story is the key trigger," he says. Dalmia is a shining example of a homegrown cement player registering impressive growth. From 3 mt in 2000, his company's capacity has now increased to 14.3 mt.

"Today, Dalmia's capacity is more than twice that of Lafarge. There was a time when it was the other way round," points out Anil Singhvi, chairman of Ican Investments Advisors and former MD of Gujarat Ambuja Cements.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Image: Puneet Dalmia, Managing Director, Dalmia Bharat Enterprises.Photographs: Courtesy, Outlook Business

Indeed, the only foreign cement company that has made its presence felt is Holcim, albeit through its buyout of Gujarat Ambuja. Together, Ambuja and ACC (both Holcim entities) now have a capacity of 52 mt, compared to 33 mt at the time of the buyout in 2005.

Of course, during the same six years, Indian companies have grown much more. For instance, UltraTech, a AV Birla Group company, has increased capacity to 52 mt (from 31 mt) after a round of mergers and acquisitions.

Overall, foreign companies just haven't grown fast enough to reap the benefits of the boom in housing and infrastructure.

If Lafarge and others didn't grow quickly, Hutch/Vodafone's mistake was in not growing wide. Then, Hutch's decision to restrict itself to affluent customer circles probably made a lot of sense. Now, it's obvious that the move helped rival Bharti Airtel charge ahead.

Once it took charge, Vodafone made a pan-India presence a priority, but it was too late. "The first-mover advantage is a big thing in telecom. In that sense, the gap between Bharti and us may remain for a while," concedes Samaresh Parida, strategy director, Vodafone Essar.

He says that once Vodafone acquired Hutch, the intention to scale up quickly was top priority. "Seven circles were added in three years. That was hugely critical," adds Parida.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Image: Atul Bindal, President, Mobile Services (India and S Asia), Bharti Airtel.Photographs: Courtesy, Outlook Business

What's Bharti's reading of the situation? "When other operators were focusing on the metros and large towns to be their revenue driver, we decided to expand into smaller towns and villages. We got into areas like the North-East when no one was keen on it," recalls Atul Bindal, president (mobile services, India & South Asia), Bharti Airtel.

Is that what helped his company hold on to prime position? "It is really a combination of pioneering an innovative, scalable, low-cost business model and quite simply the ability to take risks and be entrepreneurial in nature," he says.

Bharti was the first to outsource its network management and IT services. Cost management aside, this helped Bharti focus on growing its mobile services business. "More than anything else, it pays to have a flexible and an agile approach to the business," says Bindal.

It is this agility that has worked well for Indian companies, especially when it comes to spotting a business opportunity, taking calculated risks and backing it. When Tata Steel bought Corus in 2007, it was an audacious bid; the entire group's turnover wasn't much more than Corus' toplines.

But when the $12 billion buyout happened, it catapulted Tata Steel from the mid-50s of the global pecking order to among the top five. Today, Tata Steel is a Rs 1.18 lakh crore (Rs 1.18 trillion) company with a presence across five continents.

Typically, the success in executing a deal of this nature is contagious and confidence levels across the group if not across the industry -- rise. And that comes in handy when dealing with the domestic market.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Image: Pawan Goenka, President, AFS (Automotive, Farm Equipment Sector), M and M.Photographs: Courtesy, Outlook Business

Foreign companies, in contrast, often falter when faced with the inherent complexity of the Indian market.

"Although multinationals think of India as one market, it is actually very nuanced. Besides, most multinationals have global standards and are process-driven, which makes it hard to make an exception for just one market," points out Ananth Narayanan, partner, McKinsey & Co India.

Tractors is one sector, for instance, where the inability to be flexible has cost multinationals dearly. Together, the top three local manufacturers -- Mahindra, Tafe and Escorts -- have cornered about 75 per cent of the market, leaving precious little for the overseas players. John Deere and New Holland, both players of international repute, have been around for over a decade but continue to remain at the periphery.

Over the years, Indian manufacturers have sustained their rural focus with sensible overseas forays. Not only does India account for over a third of global tractor sales, it remains the fastest growing tractor market in the world (during FY11 482,000 tractors were sold in India compared to 300,000 in China, the next largest market).

They've also acquired judiciously: M&M bought out Punjab Tractors, while Tafe acquired Eicher and grew to be a $1 billion company. Pawan Goenka, president, AFS (automotive & farm equipment sector), Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M), also thinks the 'trust factor' in this business is a critical component.

"There is a greater level of comfort with an Indian brand. Tractor owners do not shift brands easily," he says. M&M is the largest tractor company in the world by volumes, with operations in the United States, China, Australia and several countries in Africa. It also has a 40 per cent market share in India.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Reuters

"This is a B2C business where the equity of a brand and customer loyalty are very important," says Goenka.

It helps that M&M has well understood how price sensitive the Indian market is. It recently launched the cheapest tractor: Yuvraj is a 15 hp machine that carries a Rs 1.75 lakh (Rs 175,000) tag.

That aside, there's also Mahindra & Mahindra Financial Services, a non-banking finance company that provides finance with a rural and semi-urban focus, for utility vehicles, tractors and cars.

"This is a big enabler for the tractor business," admits Goenka. "Multinationals often find it difficult to compete in an Indian market that excels at frugal engineering," adds McKinsey's Narayanan.

Difficult terrain

Multinationals entering India tend to do so in two ways: either by setting up independent entities or, as is becoming more common, through acquisitions.

Be it Holcim's buyout of Ambuja and ACC, Abbott's acquisition of Piramal's healthcare solutions business, Daichii taking control of Ranbaxy or Heidelberg now owning Mysore Cement, the M&A route has provided a ready access to a huge market. That comes with its own set of problems, though.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Reuters

According to Singhvi, multinationals tended to acquire companies that had a high entrepreneurial drive quotient.

"But over time, the Indian company became just a subsidiary. Besides, India being an emerging market meant it did not receive sufficient attention," he explains.

The acquired companies transitioned from independent decision-makers to being bogged down by bureaucracy and hierarchies, to the multinationals' detriment.

"It is important to be flexible in India where in a CEO-owner scenario, decision making is easier for the home-grown companies," says Narayanan.

Globally, says Pankaj Ghemawat, Anselmo Rubiralta Professor of Global Strategy at IESE Business School in Barcelona, large corporations have the notion that if they have succeeded in their home market or other large markets, the new market won't be too different. And that isn't always correct. Ghemawat cites the example of Walmart's Brazilian experience.

"They took 10 years to get it right," he points out. Where Walmart erred was in not understanding the peculiarities of the new market: it opened US-style large-format stores in Brazil, which is a small-format store country.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Reuters

The mega retailer succeeded only many years later, after it reduced store size and acquired local chains that had already got the formula right.

In a world where the term emerging markets is used often and loosely, India is frequently clubbed with Brazil, Russia and China.

How different the Indian market is, is something that is rarely understood. "For over a hundred years, most companies in the world focused on serving about 200 million consumers each in the US and Europe and about 100 million in the rest of the world," says Janmejaya Sinha, chairman (Asia Pacific), Boston Consulting Group.

The size of the Indian market for their products was not as large, which did not make it necessary for them to study the consumers here. "Their product departments did not actually design products that these consumers needed but only tried to push the products they had made. Such multinationals found the consumers difficult," he maintains.

What also played spoilsport was the complexity of India. "These companies needed to understand its federal nature, influence of the State and the complexities of the supply chain and distribution."

This is where the 'one size fits all' approach comes apart completely. In other words, what works globally is almost certain not to work here. Take the paints industry, where globally the decorative and industrial segments are equally divided.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

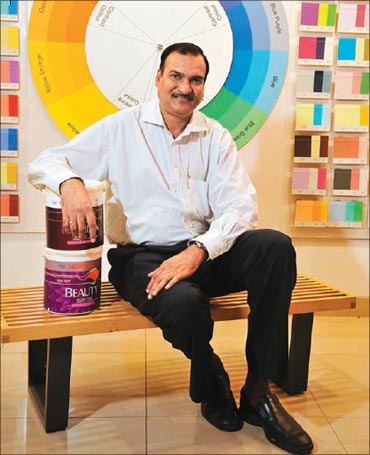

Image: HM Bharuka, Managing Director, Kansai Nerolac.Photographs: Courtesy, Outlook Business

In India, the former accounts for 75 per cent of the market, in line with the boom in housing. Market leader Asian Paints (35 per cent share) has consistently maintained its lead for several years. It is also a strong player globally -- operations in 17 countries with 23 manufacturing facilities.

The company's Rs 7,706 crore (Rs 77.06 billion) FY11 turnover is seven times more than AkzoNobel and three and a half times that of Kansai Nerolac.

Competitor Kansai Nerolac's parent is the leader in paints back in Japan; in India, 55 per cent of its revenues come from the decorative segment. But that's still below the industry average (75 per cent) and far less than Asian Paints' 90 per cent -- it doesn't help that Kansai has only 13,000 outlets compared to 27,000 for Asian Paints.

"The most important thing in decorative paints is mindshare and that cannot be won overnight. Besides, success here depends on how quickly your product can get across to remote locations," states HM Bharuka, managing director, Kansai Nerolac.

He admits that while his growth from the decorative segment will have to increase, it is anything but easy. "This is a semi-FMCG business. The key challenges are getting mindshare and increasing the frequency of painting," he says.

Going overseas -- From India

One reason Indian companies are doing well at home is the confidence they've gained from their successes abroad.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Image: Neeraj Kanwar, Managing Director, Apollo Tyres.Photographs: Courtesy, Outlook Business

Dealing with new sets of customers, integrating businesses, coming to terms with supply chain differences and coping with new regulatory environments has given Indian companies invaluable experience that's made them tougher competitors back home.

Apollo Tyres's 2006 acquisition of the Dunlop Tyres International facility in South Africa is one such case. In the past five years, Apollo has significantly built its presence in the South Africa, where it commands a 20 per cent marketshare against companies like Goodyear, Bridgestone and Continental.

While India still contributes 62 per cent of Apollo's revenues (FY11: Rs 8,868 crore -- Rs 88.68 billion), the South African business' share is a healthy 13 per cent; the rest comes from Europe.

"We took the decision to go international in 2005. At that stage, we wanted to be a $2 billion company by FY11," says Sunam Sarkar, the company's CFO.

One of the objectives was to derisk the business from being too India-centric (the tyre industry went through major turmoil in the 1990s when several players exited the business). In his opinion, the key challenges are understanding of the market, investment in technology and getting it right on distribution.

Apollo Tyres MD Neeraj Kanwar calls his company an Indian MNC. "We want to be in the league of top 10 manufacturers in the world over the next five years. We will do this by expanding our areas of operation, manufacturing base and entering new product segments," he says.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Reuters

If Apollo was against the global best in South Africa, it is a different story in India. Here, the the top four players -- MRF, Apollo, JK and Ceat -- are all Indian and account for 75 per cent of the market.

Foreign players, including Bridgestone and Goodyear, account for barely 10 per cent of the market. Even in terms of revenues, the foreign players have not been impressive: Goodyear's Rs 1,320 crore (Rs 13.20 billion) turnover compares unfavourably with MRF's Rs 8,120 crore (Rs 81.20 billion).

Why do Indian companies have such a definite edge in the tyre industry? Perhaps because the multinationals have largely ignored the high-growth two-wheeler segment.

Competitive pricing, plants at several locations to take advantage of freight and octroi differences and aggressive distribution strategies worked to domestic players' advantage, which their foreign rivals didn't realise until it was too late.

Getting it all wrong

Clearly, India remains a grey area for the multinationals. Their approach of treating the country's many markets like any other emerging market has backfired in several cases.

As a result, they're often clueless about what to do next. "The distinctive feature about India is that its per capita income is about a third of China's and a tenth of that of Brazil. The fact is these countries, by themselves, are very different," emphasises IESE's Ghemawat.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Image: Thomas Kuehl, Board Member and Director (Sales and Marketing), SkodaAuto India.Photographs: Courtesy, Outlook Business

That point of view has many takers and McKinsey's Narayanan says, "While India is not really comparable, it comes closest to the Chinese market of five to seven years ago in terms of complexity and breadth of customer needs."

This is where the intricacies of India's demographics come to the fore. Thomas Kuehl, board member & director (sales and marketing), SkodaAuto India, succinctly says, "India is a complex market with changing preferences every few kilometres."

According to him, an understanding of these complex demographics calls for a combination of voracious research and a solid understanding of the marketplace.

"Indian companies appear to have a slight edge over multinationals in terms of understanding their consumers well," says Kuehl.

That's particularly true when it comes to offering products that are seen as value for money. For many years, global car companies brought in models that were doing well in other markets (such as Opel Astra, Fiat Siena and Mitsubishi Lancer).

Trouble was, these also carried price tags more suited to those foreign markets. The result: companies like Fiat and General Motors found the going very difficult. The market in India is about small cars (85 per cent of the market) and affordability.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Rediff Archive

Tata Motors is a company that's absorbed that learning really well. Compared to big names like Fiat, Ford, General Motors and Toyota, Tata was primarily a truck manufacturer when it entered the passenger car with its Indica model.

Today, after launching the Indigo, Manza, Aria and the Nano, it has a 13 per cent share of the passenger car market. Clearly, having an offering across several price points works.

As does an extensive distribution network: 619 dealer outlets, compared to 81 for Skoda across 52 cities and 173 outlets for Ford across 102 cities. After sales service is often the deal breaker (or clincher) in sales of passenger cars. "Dealer expansion could be a hurdle for the multinationals," admits Kuehl.

Of course, the 'foreign' Maruti is still king of Indian roads, with 933 outlets and a market share of 48.74 per cent. Hyundai's performance is nothing to be sneezed at, either: 18.1 per cent marketshare and 315 dealer outlets. But these are the exceptions, rather than the rule.

Skoda's Kuehl is candid about why international car manufacturers have to rough it out in India. "The biggest reason is the cost of ownership. Indian consumers always look for low cost of maintenance before buying the car," he says.

That thinking is finally seeping in. Toyota launched its Etios sedan in India first, while GM and Ford have also launched small cars here.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Reuters

The distribution issue

Distribution and extended presence is an issue in other sectors as well, such as mutual funds. "The nature of distribution here is such that the top 10 cities are over-served while the rest are severely under-served," says Nimesh Shah, MD & CEO, ICICI Prudential Asset Management.

The trick is to reach out as easily to a customer in Bhagalpur as to one in Bengaluru, and this is where many multinationals falter. The numbers tell the story: according to data from the Association of Mutual Funds in India, eight of the 10 mutual fund companies are Indian.

The largest is Reliance, which had assets under management (AUM) of Rs 101,577 crore (Rs 1,015.77 billion) as on March 31, 2011. HDFC is placed second at Rs 86,282 crore (Rs 862.82 billion), while ICICI Prudential with Rs 73,466 crore (Rs 734.66 billion) is the third largest.

Of the top 10, the Indian mutual funds have accounted for 88 per cent of the total AUM of Rs 5,57,249 crore (Rs 5,572.49 billion).

One argument often put forth is how Indian mutual funds are more prone to sticking it out with their investors.

"Earning investors' faith through market cycles is a key element. This requires consistent and clear communication apart from a long-term approach to the business," emphasises Shah.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Image: Derek Jones, Director (Marketing), SabMiller.Photographs: Courtesy, Outlook Business

He points to an internal study by ICICI Prudential -- almost 87 per cent of the company's assets under management are in the top quartile in the relevant horizon.

Harshendu Bindal, president of Franklin Templeton Asset Management (India), admits Indian players have potential advantages in terms of recall and distribution.

But, he adds, "this is only if their sponsors belong to established financial services firms or corporate groups. As a foreign player, we had to work hard to put in place distribution relationships and build brand equity."

It's relatively easy to see why Indian companies have succeeded here: they've focused on distribution and have a sounder understanding of the equity markets.

Local brands on a high

Indian companies score over MNCs in the liquor industry as well. With strict regulations dictating virtually all aspects of the business, including advertising and brand promotion, companies need to work harder to ensure that their brands are available on every storeshelf possible.

But liquor is also characterised by immense brand loyalty among consumers. And they're fussy about taste. Which explains why players like San Miguel and Stroh's -- which didn't taste 'Indian' enough -- lost their fizz very quickly.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Reuters

It helps, of course, that market leader United Breweries (which manufactures Kingfisher) launched new brands at various price points. The numbers speak for themselves.

The UB Group, with its subsidiaries, stands out with a commanding market share of over 50 per cent in the beer segment, according to data from Euromonitor. Its flagship brand, Kingfisher, accounts for 41 per cent, while its closest competitor, SabMiller, has a 31.8 per cent share and counts brands like Haywards, Knock Out and Foster's in its portfolio.

According to Derek Jones, director (marketing), SabMiller, beer accounts for 5 per cent of the total alcohol consumed in India.

"While the per capita consumption of spirits in India is 65 per cent of the global average, it is 5 per cent in the case of beer. This presents a significant opportunity in terms of increasing the overall size of the pie," he says.

International brands like Carlsberg, Budweiser and Tuborg together account for less than 5 per cent of the market.

The story in spirits is not very different. This high-margin segment, accounting for over 90 per cent of the overall market, has UB's market share at 42 per cent. This comes from its brands like McDowell's, Bagpiper and Old Tavern.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Reuters

Rival brands include Royal Stag (4 per cent) and Blender's Pride (1.1 per cent) -- owned by Pernod Ricard. Indeed, the UB Group isn't big only in India -- it's the third-largest spirits company globally.

"In India, as also elsewhere, we have concentrated on developing local brands with growth potential; developed new brands and introduced our international brands into the market," says Jones.

If Hayward's (SabMiller acquired this from Shaw Wallace) has almost 20 per cent of the market, Foster's (an Australian import) is at a miniscule 2.1 per cent. That goes some distance to demonstrate how an international brand does not work all the time in India.

Dancing to the tune

The need for multinationals to succeed here comes from just the sheer growth momentum. In larger and more developed markets, a 3-4 per cent growth rate for most industries is normal.

By contrast, India has witnessed industries like passenger cars growing quite frenetically in the last few years. BCG's Sinha forecasts there will be an additional billion consumers that will join the marketplace in the next decade.

"By then, the incremental consumption of Asia Pacific of $15 trillion will be more than the incremental consumption of US and Europe together of about $8 trillion. And these will be different consumers," he explains.

. . .

Powered by

How, why Indian firms are knocking out MNCs

Photographs: Reuters

For the multinational, the option is clear -- deal with this huge, emerging segment or continue catering to the market that they are serving, which will grow less sharply.

"Those who can learn to serve the new segment well will find new consumers that will sustain them for a long time to come," Sinha predicts.

But it's not all doom and gloom for multinationals in India. Far from it. Their dominance is all too visible in areas like consumer electronics, IT and FMCG -- think LG, Samsung, IBM, Unilever, P&G and Nestle.

And here, it's the turn of Indian companies to struggle. There are clear reasons why they do not make the cut -- the investment of time, money required in R&D and the need for a technological thrust.

Evidently, the experience gained by multinationals in building big brands globally has been useful even in a multi-faceted market like India. There is some serious learning to be made here before Indian companies get to a position of dominance.

Perhaps the success encountered by their counterparts in other sectors could be the much-needed trigger. Clearly, this story doesn't end here. Not yet.

Outlook Business, June 25, 2011

Powered by

article