The lack of change in policy can be hugely damaging not only for foreign investors but also for the Indian economy and domestic industry, says A K Bhattacharya.

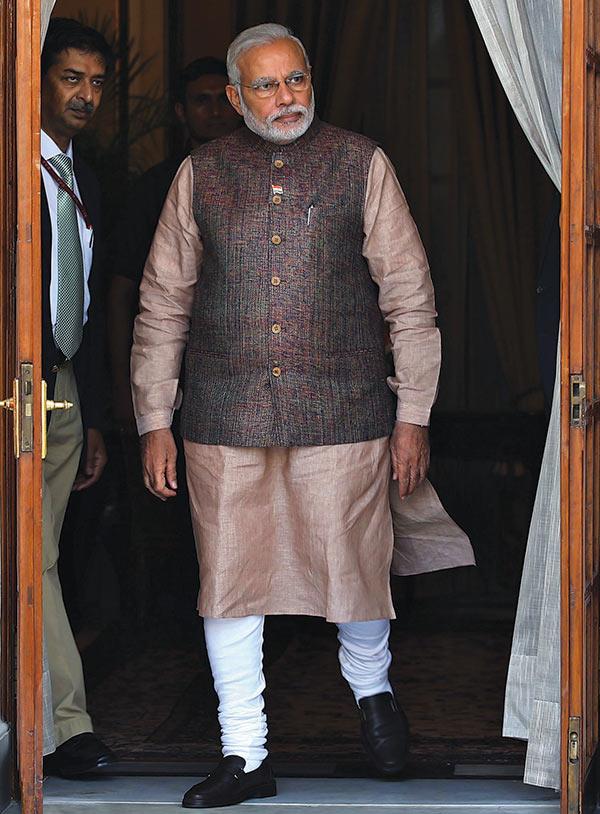

The flurry of decisions that the Narendra Modi government is taking in different spheres of the economy suggests that policy-making in this country has been wrongly criticised for its excruciatingly slow and halting nature.

For instance, the Modi government's first Union Budget was presented by its Finance Minister Arun Jaitley on July 10, promising, among other things, higher foreign direct investment (FDI) of up to 49 per cent in defence and insurance.

Even though the Budget is yet to receive the President's assent, the government has held several rounds of discussion on the procedural formalities to be followed for allowing 49 per cent FDI in defence.

And for insurance, the Cabinet met last week to approve a legislative Bill to raise the foreign investment ceiling in insurance from 26 per cent to 49 per cent. If all goes well, the new insurance Bill may be introduced in the current session of Parliament and even get approved.

That, indeed, would be considered fast work. But would the international business community have the same perception? Foreign investors are likely to take this accelerated pace of policy-making with a pinch of salt.

...

Their outlook will be influenced by what happened in India in the last decade. In spite of the current pace of activity within the government, the general impression that policy changes in this country take place at a slow speed is unlikely to change. There are good reasons that make it difficult to dispel this impression.

Take a look at the key legislative or even the non-legislative policy changes that have been mooted recently and you will realise that nothing can happen in this country in less than 10 years.

Now, 10 years is a long time. The lost opportunity because of the lack of change in policy can be hugely damaging not only for foreign investors but also for the Indian economy and domestic industry.

For instance, the idea of raising the FDI limit in insurance ventures was mooted in 2004 by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) in its first term.

It took another four years to table a Bill to amend the insurance law to facilitate the increase in FDI in this sector. The Bill was then sent to a standing committee of Parliament for scrutiny. Another three years passed by before the committee made up its mind.

And guess what the committee concluded? That the FDI ceiling for insurance should stay at 26 per cent! And who headed that committee? A member of the Bharatiya Janata Party. But by that time, seven years had been lost.

...

It was only in late 2012 that the UPA government, in its second term, decided to get Cabinet approval for a revised Bill to raise the FDI limit to 49 per cent. And it had the political smartness to table the new Bill in the Rajya Sabha in 2013, so that Bill will stay alive even after the elections and the formation of a new Lok Sabha in 2014.

And now, a year later, the National Democratic Alliance government amends the Bill with the new clauses on Indian management control and clubbing FDI and foreign institutional investment within the 49 per cent ceiling.

Even if the current Bill is passed by Parliament and becomes law, it is unlikely that the investing community - at home or abroad - will forget or even forgive the Indian government for its 10-year long decision-making process to raise the foreign investment limit in the insurance sector.

The story is no different for other key reformist policy proposals in the last decade or so. The much-discussed Goods and Services Tax (GST) was first mooted by P Chidambaram in his Budget for 2006-07.

The target date he had set for implementing the new tax regime, which would have been the biggest tax reform after the initial burst of the early 1990s, was April 2010. That was an ambitious target. The empowered committee of state finance ministers managed to finalise its first discussion paper only in November 2009.

A Constitution amendment Bill, necessary to institute the new tax administration for states and the Centre, was introduced in March 2011. That Bill appears to have lapsed since it was tabled in the Lok Sabha. Three years have passed since then.

...

The new government has not given any new dates for the launch of the GST, but this new taxation regime, too, is unlikely to be a reality before the 10-year period is over.

In other words, do not expect the GST to be in place before 2016, unless the government decides to introduce a diluted version like a central GST and wait for states to join the new regime over time.

The Direct Taxes Code, which was expected to revamp the decades-old income-tax statute, was talked about for the first time in 2008. Five years later, a Bill was readied and tabled. The new government has not yet applied its mind on how to introduce it and in what form.

Similarly, the controversial policy on FDI in retail was mooted in 2005 but was notified only in 2012 for single-brand retail and in 2013 for multi-brand retail, with stringent conditions, of course.

Taking a look at the pace of all these key economic policy decisions, it will not be incorrect to conclude that in India, any major policy change takes at least seven to 10 years. In some cases, it could take even longer.